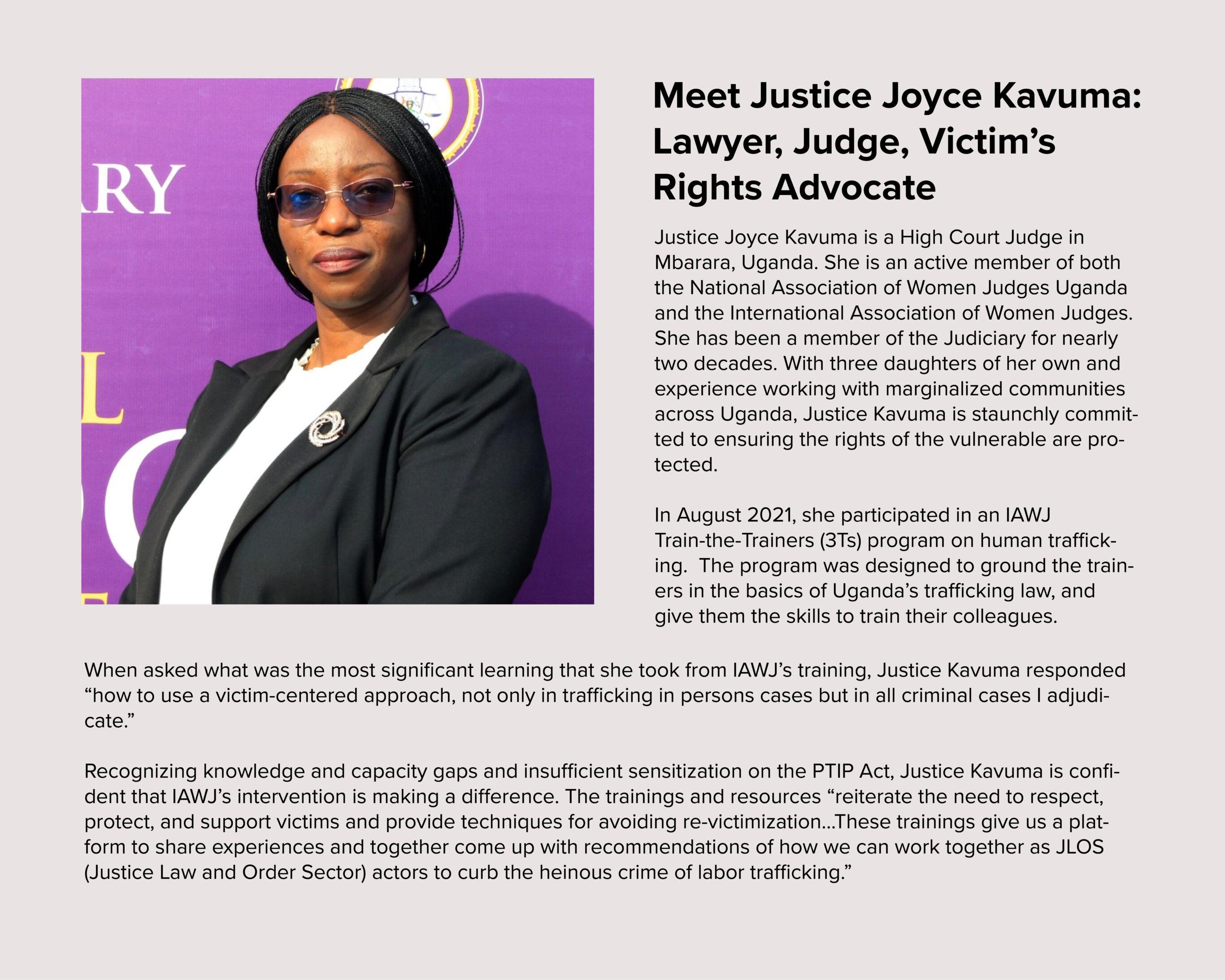

This post is co-authored with Justice Joyce Kavuma and the International Association of Women Judges.

In the first of a series of training modules prepared by the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) for judicial officers in Uganda, learners are presented a case scenario to demonstrate how courts and judicial processes can re-traumatize a victim.

They are first asked to look at a photograph depicting a young woman standing before a judge. She is the complaining witness in a rape trial. Beside her is the prosecutor and nearly a dozen other men. Most of them are counsel for the defense. One, barely visible in the background, is her father. Another, just a few feet away, is the defendant, the man she accuses of assaulting her.

Stepping back from the photograph, the trainers provide additional case details. The witness, as the judge informed all parties, waived her right to a forensic examination. The judge nor the witness provide further explanation, but the trainers offer additional context. In the jurisdiction where this case is being adjudicated, a forensic examination requires the accuser to identify the accused in the physical space of a forensics lab. This is to ensure that the accused cannot solicit another person to submit DNA. In instances where the accusing party lives a distance from the lab, transport is provided. The accused is entitled to the same, meaning accused and accuser may be transported together in the same vehicle, sometimes over a distance as great as 8 hours.

The trainers open the session on victim-centered approaches with this study to show how a case might look different when viewed from a victim’s perspective. Understanding that certain practices can inflict further harm, judges can play a critical role in ensuring victims are not re-traumatized by their experiences in the courtroom. While judges are trained to protect the rights of criminal defendants, a “victim-centered” approach serves as a reminder that victims, too, have rights that judges must protect. Building victim-centered courts is not to tip the scale against neutrality but simply to level it.

Labor Trafficking in Uganda

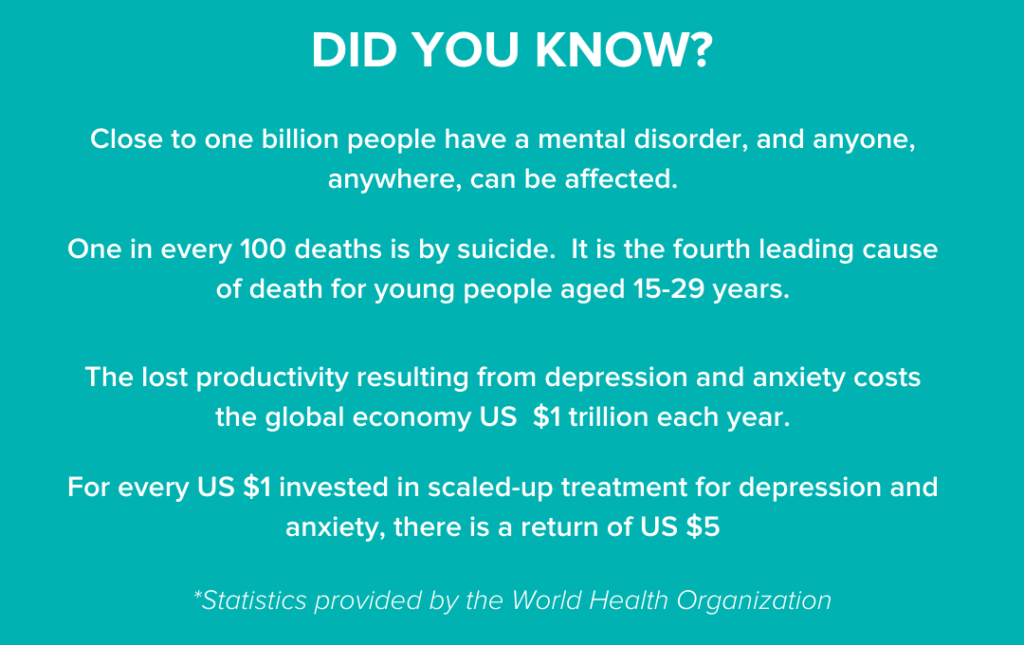

Africa is the world’s youngest continent; almost 60% of the current population is under the age of 25. As Africa’s population is expected to double by 2050- from 1 billion to nearly 2.4 billion inhabitants-it is apparent that this youthful trend will continue. What is also apparent is that many African economies are struggling to absorb this youth bulge, leading to high youth unemployment rates across the continent. Even among those who do have a job, the vast majority –almost 95%- work in the informal economy.

In Uganda, where more than 75% of the population is under 30, youth unemployment rates are among the highest in Sub-Saharan Africa. This is especially true in rural areas where most of Uganda’s youth reside, and especially true for girls who are far less likely to enroll and complete their education than boys. The unemployment rate for girls and women is more than double that of boys and men.

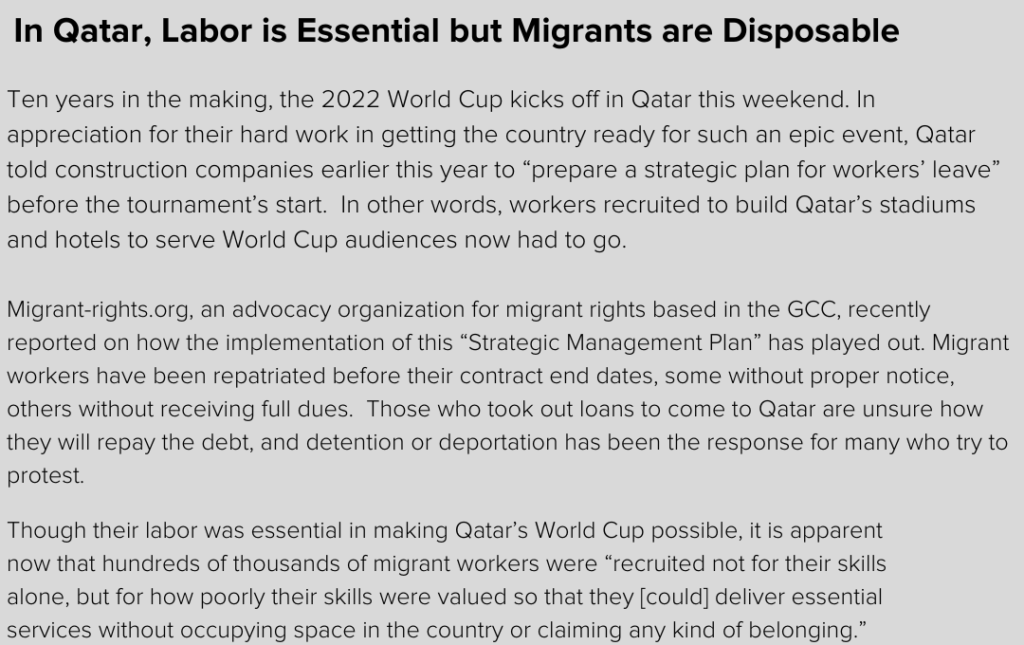

Poverty and lack of employment opportunities are a key driver of migration in the region (for more on drivers of migration, read our previous post.) While much migration in Uganda is internal, primarily from rural to urban areas, neighboring countries, including Kenya, continue to attract both skilled and unskilled migrants from Uganda. Uganda is also a destination country for labor migrants from other countries in the region. In recent years, migrants have increasingly begun to look beyond the continent, particularly to the Middle East for employment opportunities. It is estimated that remittances to Uganda’s economy from people working in the Middle East increased from $51.4 million in 2010 to $309.2 million in 2018.

While a boon to the economy and the families that these remittances support, migration is not without risk, especially for the thousands of women employed as domestic workers in Middle Eastern homes. The majority of international trafficking cases identified in Uganda involve young women trafficked into domestic service in the Middle East.

While Uganda continues to implement measures to prevent trafficking, including cracking down on illegal recruitment agencies and investing in awareness raising activities, the justice sector similarly must take action. To ensure victims and survivors of trafficking are not re-traumatized by the justice system, judicial officers must be trained in victim-centered and trauma-informed approaches. This is exactly what IAWJ, with support from the Global Fund, is doing in Uganda.

How Justice Systems Can Re-traumatize Trafficking Survivors

In Uganda, the rights of the accused are outlined and upheld in national law and justice systems. The Ugandan Constitution, for example, provides for the accused’s right to a fair hearing including the right to a speedy and public trial; the right to presumption of innocence until proven guilty; the right to legal counsel; and the right to appear before the court in person. While upholding the rights of the accused is foundational to any meaningful justice system, the rights of the victim must be similarly upheld. This is especially true in trafficking cases where the potential to inflict further trauma runs high.

The 2009 Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act (PTIP Act) and its corresponding regulations (2019) encourage a victim-centered approach and impose responsibilities on law enforcement, prosecutors, judicial officers, and other government officials to protect and support victims. Indeed, it sets out specific measures to ensure victims are protected and supported. These include not penalizing victims for any crimes committed as a direct result of being trafficked; providing victims access to health, social, medical, counseling and psychological services where possible; protecting the privacy and confidentiality of victims; and providing for compensation and restitution of victims. The PTIP Act lays out clear measures for supporting a victim-centered approach. The problem? Very few people know what it is.

Trafficking is a complicated and multi-faceted crime, and the laws designed to prevent, prosecute and punish it are relatively recent innovations. One of the challenges of combatting this modern form of slavery is that in the absence of stakeholder training and awareness, trafficking victims are likely to come to court not as victims/witnesses, but rather as civil or criminal defendants. They may be accused of violating immigration laws, charged in labor disputes, or indicted for petty theft (in cases where the defendant is acting under the control of another.) Judicial actors who know and understand the trafficking statute may recognize that this is at base a trafficking situation. They may then be able to refer the matter for investigation and prosecution. At a minimum, if judges and judicial sector officials have the knowledge and skills they need, they can avert further injustice to the victim — who may be in court as a criminal defendant. This is why continuing judicial education is so important.

How IAWJ is Strengthening the Justice Sector’s Response

As part of its training, IAWJ seeks to equip justice sector actors to identify possible TIP victims in such cases. They train participants to recognize red flags of human trafficking and ask appropriate screening questions. Justice Kavuma, notes that until and unless judicial officers undergo training, such as that provided by IAWJ, identifying victims will remain a challenge.

Unless we are linked together, the chain of justice breaks.

— Justice Joyce Kavuma

Training individual justice sector actors in victim-centered approaches can help ensure survivors access justice and support services. But to ensure victim-centered and trauma-informed approaches at every stage of the criminal justice process, they must be embedded at the local and regional levels. IAWJ’s “Train the Trainers” program drew participants from across districts who can then share that knowledge with judicial officers in their own communities.

IAWJ also supports regional dialogues to build and strengthen a coordinated cross-border response. Judges and Magistrates from Kenya and Uganda gather to share information and experiences and collaborate on best practices to address trafficking in persons and support victims and survivors. “We all work together like a chain. Unless we are linked together, the chain of justice breaks.” For Justice Kavuma, the significance of cross-border dialogues and a coordinated victim-centered approach is paramount if trafficking is truly to be eradicated. IAWJ is currently developing a bench book to reinforce this message.

Justice systems play a critical role in combatting trafficking. Rooting them in trauma-informed and victim-centered approaches is how we ensure these systems support recovery and not re-traumatization.

If you are interested in partnering with the Global Fund, please reach out.

The program referenced in this article is funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

The International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) is a non-profit, non-governmental organization whose members represent all levels of the judiciary worldwide and share a commitment to equal justice for women and the rule of law. Created in 1991, the IAWJ has grown to a membership of over 6000 in 100 countries.