Centering victims in justice systems is how we support recovery and not re-traumatization

In Uganda, Women Judges are Leading Efforts to Ensure Justice Systems Heal not Harm

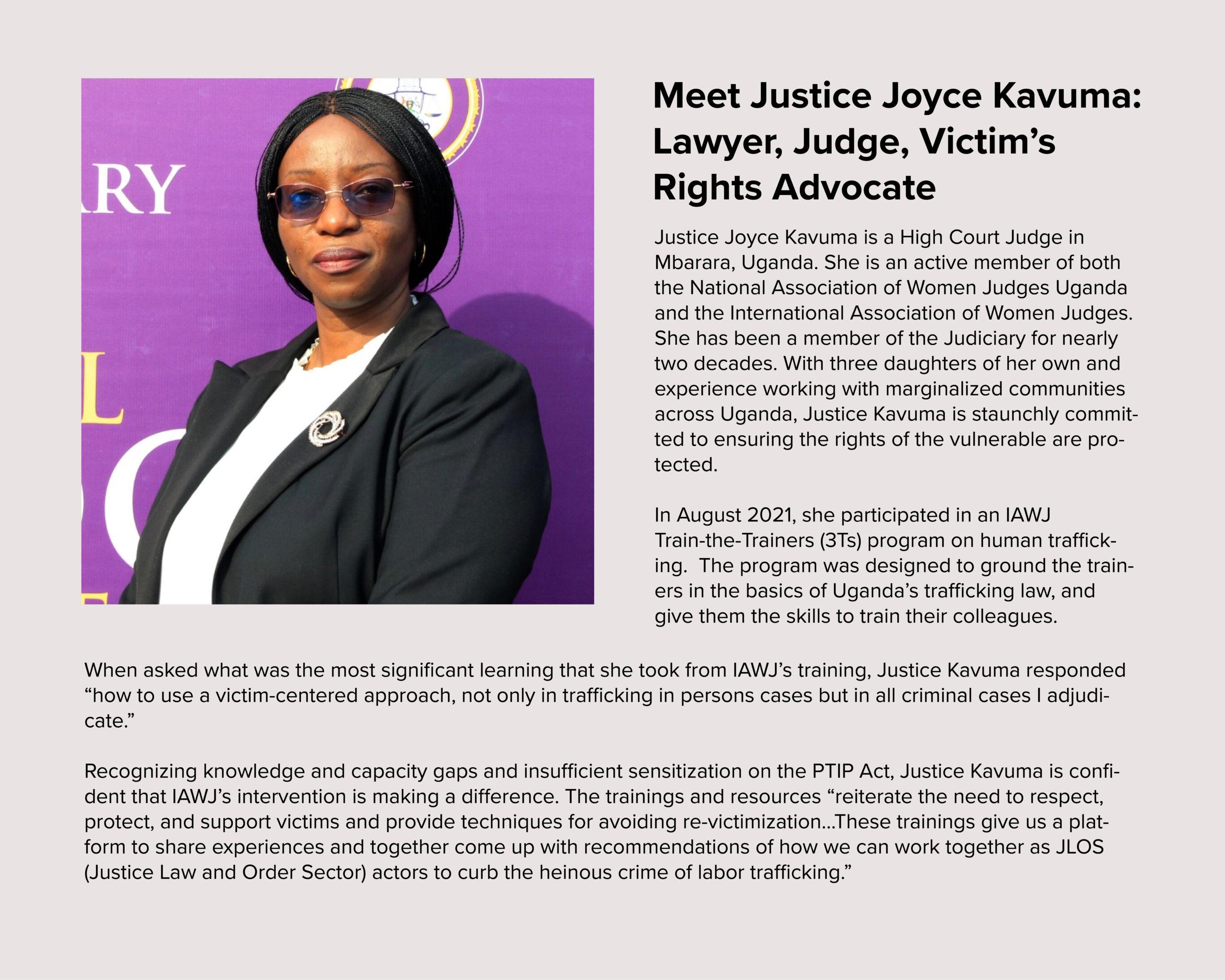

This post is co-authored with Justice Joyce Kavuma and the International Association of Women Judges.

In the first of a series of training modules prepared by the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) for judicial officers in Uganda, learners are presented a case scenario to demonstrate how courts and judicial processes can re-traumatize a victim.

They are first asked to look at a photograph depicting a young woman standing before a judge. She is the complaining witness in a rape trial. Beside her is the prosecutor and nearly a dozen other men. Most of them are counsel for the defense. One, barely visible in the background, is her father. Another, just a few feet away, is the defendant, the man she accuses of assaulting her.

Stepping back from the photograph, the trainers provide additional case details. The witness, as the judge informed all parties, waived her right to a forensic examination. The judge nor the witness provide further explanation, but the trainers offer additional context. In the jurisdiction where this case is being adjudicated, a forensic examination requires the accuser to identify the accused in the physical space of a forensics lab. This is to ensure that the accused cannot solicit another person to submit DNA. In instances where the accusing party lives a distance from the lab, transport is provided. The accused is entitled to the same, meaning accused and accuser may be transported together in the same vehicle, sometimes over a distance as great as 8 hours.

The trainers open the session on victim-centered approaches with this study to show how a case might look different when viewed from a victim’s perspective. Understanding that certain practices can inflict further harm, judges can play a critical role in ensuring victims are not re-traumatized by their experiences in the courtroom. While judges are trained to protect the rights of criminal defendants, a “victim-centered” approach serves as a reminder that victims, too, have rights that judges must protect. Building victim-centered courts is not to tip the scale against neutrality but simply to level it.

Labor Trafficking in Uganda

Africa is the world’s youngest continent; almost 60% of the current population is under the age of 25. As Africa’s population is expected to double by 2050- from 1 billion to nearly 2.4 billion inhabitants-it is apparent that this youthful trend will continue. What is also apparent is that many African economies are struggling to absorb this youth bulge, leading to high youth unemployment rates across the continent. Even among those who do have a job, the vast majority –almost 95%- work in the informal economy.

In Uganda, where more than 75% of the population is under 30, youth unemployment rates are among the highest in Sub-Saharan Africa. This is especially true in rural areas where most of Uganda’s youth reside, and especially true for girls who are far less likely to enroll and complete their education than boys. The unemployment rate for girls and women is more than double that of boys and men.

Poverty and lack of employment opportunities are a key driver of migration in the region (for more on drivers of migration, read our previous post.) While much migration in Uganda is internal, primarily from rural to urban areas, neighboring countries, including Kenya, continue to attract both skilled and unskilled migrants from Uganda. Uganda is also a destination country for labor migrants from other countries in the region. In recent years, migrants have increasingly begun to look beyond the continent, particularly to the Middle East for employment opportunities. It is estimated that remittances to Uganda’s economy from people working in the Middle East increased from $51.4 million in 2010 to $309.2 million in 2018.

While a boon to the economy and the families that these remittances support, migration is not without risk, especially for the thousands of women employed as domestic workers in Middle Eastern homes. The majority of international trafficking cases identified in Uganda involve young women trafficked into domestic service in the Middle East.

While Uganda continues to implement measures to prevent trafficking, including cracking down on illegal recruitment agencies and investing in awareness raising activities, the justice sector similarly must take action. To ensure victims and survivors of trafficking are not re-traumatized by the justice system, judicial officers must be trained in victim-centered and trauma-informed approaches. This is exactly what IAWJ, with support from the Global Fund, is doing in Uganda.

How Justice Systems Can Re-traumatize Trafficking Survivors

In Uganda, the rights of the accused are outlined and upheld in national law and justice systems. The Ugandan Constitution, for example, provides for the accused’s right to a fair hearing including the right to a speedy and public trial; the right to presumption of innocence until proven guilty; the right to legal counsel; and the right to appear before the court in person. While upholding the rights of the accused is foundational to any meaningful justice system, the rights of the victim must be similarly upheld. This is especially true in trafficking cases where the potential to inflict further trauma runs high.

The 2009 Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act (PTIP Act) and its corresponding regulations (2019) encourage a victim-centered approach and impose responsibilities on law enforcement, prosecutors, judicial officers, and other government officials to protect and support victims. Indeed, it sets out specific measures to ensure victims are protected and supported. These include not penalizing victims for any crimes committed as a direct result of being trafficked; providing victims access to health, social, medical, counseling and psychological services where possible; protecting the privacy and confidentiality of victims; and providing for compensation and restitution of victims. The PTIP Act lays out clear measures for supporting a victim-centered approach. The problem? Very few people know what it is.

Trafficking is a complicated and multi-faceted crime, and the laws designed to prevent, prosecute and punish it are relatively recent innovations. One of the challenges of combatting this modern form of slavery is that in the absence of stakeholder training and awareness, trafficking victims are likely to come to court not as victims/witnesses, but rather as civil or criminal defendants. They may be accused of violating immigration laws, charged in labor disputes, or indicted for petty theft (in cases where the defendant is acting under the control of another.) Judicial actors who know and understand the trafficking statute may recognize that this is at base a trafficking situation. They may then be able to refer the matter for investigation and prosecution. At a minimum, if judges and judicial sector officials have the knowledge and skills they need, they can avert further injustice to the victim — who may be in court as a criminal defendant. This is why continuing judicial education is so important.

How IAWJ is Strengthening the Justice Sector’s Response

As part of its training, IAWJ seeks to equip justice sector actors to identify possible TIP victims in such cases. They train participants to recognize red flags of human trafficking and ask appropriate screening questions. Justice Kavuma, notes that until and unless judicial officers undergo training, such as that provided by IAWJ, identifying victims will remain a challenge.

Unless we are linked together, the chain of justice breaks.

Training individual justice sector actors in victim-centered approaches can help ensure survivors access justice and support services. But to ensure victim-centered and trauma-informed approaches at every stage of the criminal justice process, they must be embedded at the local and regional levels. IAWJ’s “Train the Trainers” program drew participants from across districts who can then share that knowledge with judicial officers in their own communities.

IAWJ also supports regional dialogues to build and strengthen a coordinated cross-border response. Judges and Magistrates from Kenya and Uganda gather to share information and experiences and collaborate on best practices to address trafficking in persons and support victims and survivors. “We all work together like a chain. Unless we are linked together, the chain of justice breaks.” For Justice Kavuma, the significance of cross-border dialogues and a coordinated victim-centered approach is paramount if trafficking is truly to be eradicated. IAWJ is currently developing a bench book to reinforce this message.

Justice systems play a critical role in combatting trafficking. Rooting them in trauma-informed and victim-centered approaches is how we ensure these systems support recovery and not re-traumatization.

If you are interested in partnering with the Global Fund, please reach out.

The program referenced in this article is funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

The International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) is a non-profit, non-governmental organization whose members represent all levels of the judiciary worldwide and share a commitment to equal justice for women and the rule of law. Created in 1991, the IAWJ has grown to a membership of over 6000 in 100 countries.

As the first point of contact for workers, micro-contractors present a much more relevant and effective intervention point than top down efforts

From the Bottom Up: Micro-contractors are Key to Protecting Migrant Workers in India’s Construction Industry

Ramesh* was 15 when he left his home and family in rural Uttarakhand and migrated to Delhi NCR. He had left in search of work and the opportunity to help his family whose financial situation, already precarious, had grown dire when his father became unwell. As a teenager alone in an unfamiliar city, Ramesh became easy prey for unscrupulous brokers eager to exploit his vulnerability. Deceived by a recruiter, he became trapped in a situation of debt bondage, unable to leave his employer until he managed to escape with the support of a local social worker.

For the next eight years, Ramesh worked as a daily wage laborer on various construction sites. Eventually, he progressed to obtaining work orders for minor components of construction projects and was able to hire a small team of workers. However, despite his near-decade of experience with the work itself, Ramesh was unversed in how to navigate the informal nature of the construction business. He was defrauded on multiple occasions by larger contractors and developers who took advantage of verbal agreements and informal quotations to pay him unfairly, late, or, in some instances, to default on payments entirely. Ramesh faced significant losses, losses that were born not just by Ramesh but by the team that he had hired. He was unable to pay his workers the wages he had promised. Nor could Ramesh raise his grievances with authorities. He relied on word-of-mouth relationships with these larger contractors for references and future work orders. The optimism with which he had viewed the opportunity quickly deflated. Without any real understanding of formal contracting, Ramesh and those whom he employed, were cheated, exploited, and left with no outlet for redress.

Migrant workers are at high risk of exploitation

Ramesh is one of hundreds of thousands of micro-contractors, situated at the very end of the sprawling and fractured supply chain in India’s construction sector. This sector is one of the fastest-growing in the world and accounts for 9% of India’s GDP. It is the country’s second-largest employer, attracting millions of migrant workers to urban centers each year.

The industry is characterized by a complex and multi-layered value chain that relies heavily on a floating workforce of migrant workers to meet labor demands. The majority of these workers are low-skilled rural migrants and members of socially disadvantaged communities.

Commonly, they depend on daily wages for their livelihoods, making them particularly vulnerable to exploitation. In a large-scale worker voice study with over 17,000 migrant construction workers in 2019-2020, the Global Fund found that approximately 30% of respondents experienced some form of forced labor risks, with nearly 5% experiencing critically severe forced labor conditions. More than 20% reported restrictions on their movement after work shifts, and over 10% reported facing threats to themselves and their families at their workplace.

Micro-contractors can improve working conditions but face structural constraints

Micro-contractors like Ramesh are the primary employers of this vulnerable migrant population, employing between 5 and 25 unskilled and semi-skilled workers at a time. They represent the node of the construction supply chain that is most directly connected to migrant workers – they are usually the first point of contact for workers at the end of their migration journey, and are responsible for their recruitment, scope of work, working conditions, working hours, and wages.

Their direct influence over worker well-being makes micro-contractors critical stakeholders that need to be engaged and involved in any programming efforts aimed at worker protections and welfare.

Most micro-contractors spend several years as daily wage workers and often belong to the same communities as the migrants they employ. Rising to the role of micro-contractor may seem a step up, but micro-contractors are at the mercy of structural constraints that often leave them with very few options to improve working conditions. Critically, micro-contractors regularly face irregular and delayed payments from their contractors which often limits their ability to pay timely and full wages to workers. As they are only paid when they complete a particular work order, they absorb the majority of risk as it is passed down the supply chain. Since they typically have no access to affordable financing options and often lack financial safety nets, they often take out high-interest loans through informal channels in order to stay afloat, increasing volatility and potentially trapping them in a cycle of debt bondage.

Further, most micro-contractors operate as unregistered and informally managed businesses and lack the necessary know-how to effectively structure and formalize their practices, leaving them, and consequently the workers they employ, vulnerable to exploitation and without access to channels for redress and remediation. This is the situation that Ramesh confronted. Despite his years of experience in the industry and the seeming opportunity to achieve a better future, Ramesh lacked the necessary support systems and business acumen to succeed in his new role. By extension, so too did the workers he had hired.

Addressing these systemic constraints faced by micro-contractors has the potential to generate very tangible and immediate positive effects on worker welfare.

Given the absence of clear and direct channels between big developers and the workers on construction sites, micro-contractors present a much more relevant and effective intervention point to drive worker benefits than top-down efforts through large industry stakeholders.

Between 2019 and 2021, the Global Fund and our partners worked to test this hypothesis and piloted efforts to train micro-contractors on both ethical labor practices and technical skills for business development (such as digitizing payment transactions, developing accurate quotes for work orders, and formalizing business contracts). The aim was to support the development of non-exploitative employment conditions that were mutually beneficial for workers and contractors. During this period, over 3,000 migrant workers were employed with the 570 micro-contractors trained through the project.

A large-scale quantitative study run simultaneously to this project found that workers who were employed with trained micro-contractors faced lower forced labor risks than those in the larger study pool who did not receive this intervention. Qualitatively, workers employed by trained micro-contractors expressed a desire to stay on with these employers as they had taken steps to create safe and equitable work environments, including ensuring on-time wage payments, providing safety equipment for risky jobs, and helping meet essential needs such as food, accommodation, and childcare at construction sites. Notably, women working for trained micro-contractors highlighted the non-discriminatory practices employed in the workplace. Unlike their previous experiences in the construction industry, they were now paid separately from their spouses and at an equal rate. The trained micro-contractors internalized the concept that fostering ethical relationships with workers contributes greater value on both sides. They further confirmed that technical and business practice training allowed them to formalize their work agreements and develop more secure contracts with clients to avoid payment defaults, enabling them to pay their workers on time and yielding positive outcomes with worker retention and productivity.

Buoyed by these initial learnings, GFEMS is currently investing in expanded programming in India through our partners Sattva, Labournet, and Kois Invest.

This programming is focused on providing additional cohorts of micro-contractors with access to low-cost working capital loans, channels for stable work orders, and training on ethical labor and business practices. The Global Fund views engagement with micro-contractors as a cornerstone of our approach to eliminating forced labor in the construction industry. We continue to generate evidence to build the “business case” for investing at the micro-contractor level. Trained in business and ethical practices, micro-contractors can better protect themselves and the men and women they hire. They can transform systems of exploitation.

If you are interested in partnering with the Global Fund, please contact media@gfems.org.

*Ramesh is a composite character based on research findings and discussions with implementing partners. Uttarakhand is a state in Northern India.

We need more ethical recruitment startups

We Need More Ethical Recruitment Startups

Ethical recruitment is a high priority for GFEMS, as it is for many other organizations fighting modern slavery. Ethical recruitment is a solution that offers great promise to ensure that labor migration leads to successful outcomes, and not to exploitation.

One in four victims of forced labor is an international migrant — nearly six million people. The vast, complex system of overseas labor recruitment is a key driver of outcomes for labor migrants. Transforming these systems requires a holistic approach, of which we believe ethical recruitment can be a cornerstone.

Within ethical recruitment, we take multiple approaches that we see as complementary. We engage at the policy level, as our partners International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Blas F. Ople Policy Center are doing in the Philippines and International Labor Organization (ILO) in Vietnam. We engage at the industry level, as IOM and Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) have done in multiple geographies with us. We even engage at the individual and community level, to change perceptions and behaviors related to ethical recruitment, which our partner ASK India is doing in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, for example. And we lead with evidence from start to finish, conducting prevalence estimation, worker voice studies, and synthesizing our learnings across academia, private industry, non-governmental organizations, and the public sector.

One approach the field needs to see more of is ethical recruitment startups, be they startup agencies or other relevant businesses. Social enterprises like these have tremendous potential for impact. They may not offer the same breadth as industry-wide engagement, but they offer direct, deep impact as well as second- and third-order effects that can drive industry-wide change (e.g., driving up market prices for employers, which leads to lower worker turnover). But to realize their potential, we need more social entrepreneurs to pursue these models, and we need more funding that is the right fit for them.

An ethical recruitment startup can be many things. It can be a recruitment agency. Running a recruitment agency may sound unglamorous to some aspiring social entrepreneurs, but it offers direct, tangible impact and simpler models that may appeal to entrepreneurs whose strength is in management and execution. They also often have low startup costs and low barriers to self-sufficiency.

GFEMS has already had some success with the startup approach. Fair Employment Foundation (FEF) and Seefar’s TERA are great examples of ethical recruitment agency startups. They demonstrate that an ethical recruiter can be an excellent business. It is hard to even call FEF a startup anymore, now that they have one of the leading agencies in Hong Kong and have influenced the entire market. Other pioneers and precedents are cause for optimism, too. Staffhouse, an ethical recruiter since before it was a named phenomenon, is the largest agency in the Philippines. Pinkcollar, a startup in Malaysia, was profitable less than a year after launching.

Recruitment agencies are not the only path, though. Recruitment platforms, enterprise software, migrant worker engagement tools, and other non-tech service solutions all have the potential for profitable, impactful business models that give ethical recruitment a leg up on the unethical competition. These startups will appeal more to the entrepreneurs out there who are looking for novel models or who want to apply tech skills. For example, GFEMS partner Diginex Solutions (another example of an organization that has perhaps graduated beyond the startup nomer) is developing a range of digital tools that improve the cost-effectiveness of ethical recruitment, and similar thinking could inspire other products capable of supporting a social enterprise. Sama, a migrant recruitment platform, raised over a million dollars in 2020 and has the potential to reach a scale that dwarfs even the largest of agencies.

The concepts have been proven. The precedents to believe in these approaches exist. What we need now is more. We need more social entrepreneurs entering this space. We need ethical agencies in every country of origin and destination, forming a global network of end-to-end ethical recruitment. We need an ecosystem of non-agency players who are equipping the agencies, if not offering fundamentally different models.

Equally important, we need more funders fueling these social entrepreneurs. Prevailing modes of funding are not designed for these types of ventures.

Commercially driven investors, including impact investors, are looking for the hockey-stick growth trajectory and exit timelines that do not fit the financial life cycle of an ethical recruitment agency, despite otherwise attractive economics. That could change if any of the current pioneers have breakthroughs that ignite investor attention, but we cannot wait for breakthroughs. We have to make them happen.

More frustrating, ethical recruitment startups are too unconventional or too business-like for many grant-based funding mechanisms. They are generally set up to be run like businesses, not like typical NGOs. Grant-based funders need to overcome technical hangups, like trying to fit continuous business processes into project-based intervention frameworks, and recognize the potential for large-scale, sustainable, and deep impact at a low cost. Even foundations of modest means could kickstart an ethical recruitment agency that has immediate benefits for workers and long-term impact on a larger scale.

Worth noting is that FEF, with the support of some forward-looking supporters, has launched what could be an elegant impact-investing solution that combines equity and debt to better match the needs of investors and ethical recruitment agency startups. Put this initiative in the ‘one to watch’ category (or the ‘one to support now’ category if you are a funder).

The bottom line, though, is that the anti-modern slavery field should be motivating more social entrepreneurs to pursue ethical recruitment ventures and should be supporting them with appropriate financing to be successful. They won’t necessarily all be successful. And they won’t necessarily be enough to solve all the problems of labor migration. But they offer enormous potential impact that the field has under-explored for far too long.

GFEMS looks forward to providing updates on this project and sharing our learnings with the anti-trafficking community. For updates on this project and others like it, subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.

IMPACT Project to Build Awareness, Capacity for Overseas Filipinx Workers

IMPACT Project to Build Awareness, Capacity for Overseas Filipinx Workers

Despite sincere efforts by the Philippine Government to protect Overseas Filipinx Workers (OFWs), human trafficking is especially prevalent in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). Weaker institutions, inadequately equipped personnel, and lack of community awareness pose significant challenges to effective anti-trafficking in persons (TIP) efforts. Low awareness of the risks connected to labor migration – along with the common conflation of human trafficking, smuggling, other forms of irregular migration, or other crimes – causes victims not to self-identify as such, and vulnerable communities not to recognize the warning signs.

With funding from the U.S. Department of State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, GFEMS is working to address the challenges in BARMM by partnering with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to build awareness of trafficking among the at-risk communities of BARMM and build capacity for pre-departure training service providers. IOM has a large team on the ground in BARMM, impressive expertise in local dynamics, and a previous history of successful awareness campaigns in the region.

To build awareness among vulnerable communities, IOM will work directly with the most at-risk populations to develop key messages that will be delivered through community-led awareness raising campaigns. These campaigns will primarily focus on behavioral change communications using the latest in evidence-driven communications techniques. These campaigns will target prospective migrants with little understanding of the risk of migration in order to equip them with the knowledge to increase their resilience.

GFEMS and IOM will also work to build the capacity of service providers, enabling them to train prospective labor migrants on labor migration risks, and ensure those migrants have knowledge of and access to quality support and resources, and are more resilient in the face of TIP risks and drivers. The capacity building process includes facilitating regular in-region meetings among government stakeholders to provide them with more data collection, analysis, and reporting opportunities, which will ultimately result in more evidence-based decision making and more effective anti-TIP government initiatives. In parallel, IOM will work with service providers to develop context-specific orientation materials for departing migrants, further optimizing pre-departure training.

Over the course of the project, GFEMS and IOM will conduct extensive learning and evaluation activities to determine the effectiveness of the interventions. Questions explored in the project will include:

- Does providing context-sensitized, pre-departure orientation material improve reach among vulnerable OFWs?

- Do targeted, context-sensitive community engagement and awareness initiatives increase awareness of TIP risks and drivers among at-risk communities?

- Is it possible to create early warning systems at the community level that allow us to identify individuals, families, and social segments who are most at-risk of TIP?

- To what extent is BARMM able to influence unsafe migration dynamics that transcend its borders?

GFEMS looks forward to sharing more information about this project as it is implemented, and is grateful for the support of the U.S. Department of State and the partnership of IOM.

To stay updated on this project, and projects like it, subscribe to the GFEMS newsletter and follow us on Twitter.

——

This article and the IOM project were funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

Reducing vulnerability to forced labor: Building a safe labor migration ecosystem in source communities

Reducing vulnerability to forced labor: Building a safe labor migration ecosystem in source communities

In partnership with the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), GFEMS is working with Association for Stimulating Know-how (ASK) to build a safe labor migration ecosystem in Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar, India. The migration ecosystem involves all aspects along a migrant’s journey abroad: from awareness of risks, to support provided by their family, community, and employers, to access to the means and resources to work abroad, to access to systems helping resolve issues. Focusing on major source communities for migrant labor, the project aims to reduce the prevalence of forced labor among migrant workers extremely vulnerable to slavery by creating an ecosystem that addresses specific source-side vulnerabilities.

ASK has been working for the past 27 years to build knowledge and skills for vulnerable populations and to bring about sustainable and measurable change in the lives of the people they work with. ASK’s core expertise includes planning and management of large-scale projects in the field of safe migration, sustainability, livelihoods, and health and education, with an approach to reducing community vulnerabilities grounded in economic empowerment and support services. Aligned with the Fund’s efforts to reduce the supply of vulnerable workers, ASK works closely with migrant workers to improve their economic well being and ensure stakeholder adherence to labor and human rights.

The Fund’s scoping research showed that UP and Bihar are key migrant sending states for Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Accordingly, the project provides interventions for aspiring overseas migrant workers originating from UP and Bihar. Specific vulnerabilities to be addressed by this project include: reliance on unsafe migration channels, lack of migrant preparedness in the recruitment process, lack of family and community awareness about the recruitment process, lack of support services (or use of them) for migrants and their families, economic vulnerabilities of migrants and their families, and debt bondage.

To help build a safe migration ecosystem, ASK will establish Migrant Resource Centers (MRCs) within two Civil Society Organizations (CSOs). The MRCs will deliver migrants services that reduce source-side drivers of vulnerability to forced labor. Services include pre-decision and pre-deployment training, basic paralegal and reintegration support (primarily through referrals), and assistance registering for entitlements for aspiring, in-service, and returning migrants and their families.

In parallel, ASK will build the capability and capacity of the CSOs to own and operate the MRCs beyond the project implementation period. These MRCs are a key example of the Fund’s focus on interventions that can be sustained beyond GFEMS funding, ensuring programs have continuing and long-term impact.

The dual lack of financial knowledge and access to quality financial services is a key problem for migrants and their families. Without financial literacy and access to financial services, migrants are vulnerable to economic shocks. In response, this project, with support from Mitrata Inclusive Financial Services, will test financial health innovations to determine if migrant-focused financial products or services work and if there is a market for them.

In the long term, this project will reduce migrant vulnerability to unsafe practices in the recruitment and labor migration process that often lead to forced labor. Specifically, it will ensure survivor recovery and reintegration and reduce the number of workers who pursue risky migration and who fall into debt bondage, reducing the vulnerabilities that lead to modern slavery by.

GFEMS looks forward to sharing learnings from this project in reducing source side vulnerability in India. Learn more about the Norad partnership and the GFEMS portfolio.

Subscribe to the Fund’s newsletter and follow us on Twitter to stay updated with the latest GFEMS activity.

Systemic Improvement in Survivor Care: Supporting and advancing survivor rehabilitation and reintegration in Bangladesh

Systemic Improvement in Survivor Care: Supporting and advancing survivor rehabilitation and reintegration in Bangladesh

With support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), GFEMS is partnering with the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (CAFOD) in a new project providing recovery and reintegration services to survivors of forced labor, returned migrants, and additional vulnerable populations in Bangladesh.

CAFOD is a leading, UK-based agency with over thirty years of experience working collaboratively in Bangladesh with local partners. Together with Caritas Bangladesh (CB) and Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP), CAFOD will provide immediate and long-term support to vulnerable and returned migrants and survivors of abuse and exploitation. The project will focus on reintegration support efforts in some of the highest labor-sending districts of Bangladesh.

GFEMS invests in projects that disrupt the supply of vulnerable populations and works with stakeholders to combat exploitation. To further this objective, the project will:

- Work closely with the Government of Bangladesh to strengthen survivor reintegration services and referral pathways.

- Address the social and economic challenges that vulnerable migrants and survivors experience. Through community engagement activities, the project will cultivate systemic advancements in reintegration support and survivor services, resulting in improvements to the current reintegration, recovery, and referral system in Bangladesh.

- Provide trauma-informed psychosocial and physical care to returnee migrants immediately upon returning to Bangladesh. CAFOD, Caritas Bangladesh, and OKUP will work together to refer victims and their families to support services and tools for recovery and reintegration. Further supporting returnees and vulnerable migrants in livelihood placement, CB will conduct skills assessments and develop plans for use of these skills to secure employment. With this approach to distributing resources and care, the consortium will provide holistic, needs-based support to survivors and vulnerable migrants.

- Support and advance the current referral system by improving cross-government coordination, delivery of and access to Government-provided services through engagement activities, such as reintegration, recovery, and restitution services.

GFEMS is excited to support the development of an improved system of survivor care for returned migrants in Bangladesh. By taking a needs-based approach to service delivery of healthcare, counseling, shelter, and legal support, this project ensures that survivors receive services that directly meet their needs.

GFEMS looks forward to sharing learnings from the progress of this project, and from working with CAFOD and its consortia partners, in enhancing reintegration support in Bangladesh. Learn more about the Norad partnership and the GFEMS portfolio.

Subscribe to the Fund’s newsletter and follow us on Twitter to stay updated with the latest GFEMS activity.

With Norad, GFEMS launches six new projects

With Norad, GFEMS launches six new projects

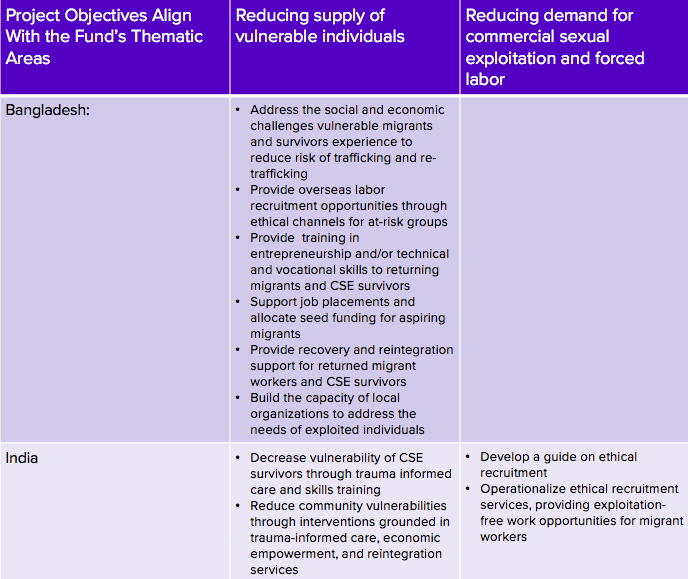

GFEMS is proud to launch a new portfolio of interventions and innovations with funding from the Norwegian Agency for Development Corporation (Norad). The portfolio represents a 5.7M USD investment in programming, with additional programming to be added later this year, and will support recovery, reintegration, and rehabilitation of survivors, as well as build safer migration systems for migrants seeking work abroad, their families, and their communities in India and Bangladesh. GFEMS is funding six projects across these focus areas, in partnership with five local, regional, and international organizations. Projects in the Norad portfolio represent an investment in evidence-based, inclusive, and sustainable interventions.

This portfolio marks a new round of in-region projects for GFEMS, following the inaugural portfolio launch in late 2018. The portfolio projects have high potential to reduce vulnerability to trafficking and re-trafficking, informed by an extensive scoping and design phase that included research into structural drivers of modern slavery, vulnerability analyses of target populations, and industry analysis in priority sectors and geographies.

GFEMS and its partners designed the portfolio to address the Fund’s strategic priorities in Commercial Sexual Exploitation (CSE) and Ethical Recruitment. Specifically, the projects test new models of ethical recruitment and support growth of existing promising models for survivor care.

GFEMS views modern slavery through an economic lens as a systemic problem driven by traffickers’ exploitation of people for profit: a consistent supply of vulnerable individuals and demand for cheap goods and services. For example, within ethical recruitment, the Fund is lowering the supply of vulnerable workers by providing support to aspiring migrant laborers and making tools for the recruitment journey more accessible, and decreasing the demand for slavery by creating incentives for ethical labor over exploitive recruitment practices. Similarly, within CSE, the Fund is working to reduce the supply of vulnerable individuals through provision of trauma informed care, economic empowerment, and reintegration services. h The Fund ensures that all stakeholders, including the private sector, work together to address modern slavery and the systems on which it relies.

Sustainability is a key priority across the projects and across the Fund’s wider portfolio. GFEMS identifies projects that leverage national priorities and meet market demands, both indicators of high potential for replication and scale. Projects provide vulnerable populations and survivors with the skills and resources they need to live safe and full lives. Within the Norad partnership, GFEMS specifically seeks to support sustainable change in the recruitment industry and provide sustainable livelihoods for survivors of modern slavery.

In the coming weeks, GFEMS is excited to share more information about the projects and partners in this portfolio. The Fund looks forward to sharing the successes and lessons learned as the projects move forward.

Subscribe to the Fund’s newsletter and Medium page and follow us on Twitter to stay updated with the latest GFEMS activity.