It’s not just another day at the office.

You Cannot Give from an Empty Cup: How One Anti-Trafficking Organization Centers Mental Health

This post is co-authored with staff from Awareness Against Human Trafficking (HAART).

It’s Thursday at 3 pm.

Like every Thursday afternoon, staff gather in a small conference room in Nairobi’s city center. Their casual chatter fades as the session’s facilitator enters. She smiles before she opens with her familiar greeting, “So, how do you feel?”

This meeting between staff and therapist has been a routine part of the HAART workweek for the last one year. Though not required, staff from all departments regularly attend. There is no formal structure or predetermined agenda. Rather, the sessions are just a way of checking in with staff, of making sure that they are ok.

The Global Fund may not be a direct service provider, but our partner Awareness Against Human Trafficking -HAART is. They have been supporting survivors of human trafficking in Kenya for over a decade- from basic needs support to psychosocial counseling to economic empowerment activities.

They work daily with girls, boys, men and women who have been abused or exploited and who are working to overcome that trauma. It’s rewarding and necessary work, for sure. But it can take a toll, and that toll can be greater than any even realize. As one member of the HAART team recalls, “I did not know I was experiencing secondary trauma, until during one of our debriefing sessions that I noticed I showed symptoms similar to those of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

While those who work directly with survivors understand the significance of mental health services for survivors, most give far less attention to their own mental wellbeing.

The daily stresses of the job are commonly overshadowed by the mission. For example, as HAART staff attest, direct service work is filled with uncertainties. “One-minute a survivor is okay, the next they are having suicidal ideation. You never know when you will receive a call for a rescue.” There is comfort in predictability. And uncertainty, especially when it is a constant, can create anxiety. But treating that anxiety is rarely top of mind when a survivor in your program is battling suicidal thoughts.

That anxiety is often exacerbated by an organization’s own limitations. There is only so much any one can do. HAART works with survivors to understand their needs and then tries to balance that with what the organization can provide.

While HAART provides counseling, training, economic assistance, school fees, health services, and legal aid to survivors, funds for victim assistance are very limited.

Staff often have to prioritize what kind of assistance to provide despite wanting to do more. And that too can be draining.

When these are your typical workday challenges- when hearing trafficking experiences recounted and watching the struggles of recovery is “just another day at the office,” mental health support must similarly be part of the job. At HAART, it is.

It’s quite admirable really to see how much emphasis HAART puts on staff mental wellbeing. Several years ago, after realizing that staff burnout was not tied to case load but to the nature of the work, HAART committed to doing more to make sure its staff were taking care of themselves, mentally and emotionally. They began small- organizing all staff hiking trips, moving office meetings outdoors, practicing yoga together. And, like all good practitioners, they listened to feedback and adapted to do better.

Since then, HAART has added two full-time mental health professionals to its team.

These professionals engage staff in group sessions, including weekly departmental-level check-ins, and provide one-on-one support for any staff who want it. There is no limit to how many sessions staff can access. Managers too keep regular meetings with their staff. Even when there’s not much to discuss, the check-ins say a lot. The opportunity to chat with a supervisor not just about work but about life helps staff “feel valued.”

Mental health is not just a focus at the top, though advice to take time off and turn off after work hours has certainly helped foster that culture. Staff have their own self-care routines; they journal, they swim, they meditate, some even make dance videos. But what’s more, particularly for the protection team, they each have an accountability partner- a person who holds them accountable for making sure self-care remains a priority.

It’s human life, and that’s a feeling of responsibility that doesn’t end with the work day.

Of course, there are times when even an accountability partner is not enough. And those days when it seems impossible to abide the best-laid guidance for mental wellbeing. As HAART staff are always aware, “it’s human life,” and that’s a feeling of responsibility that doesn’t end with the work day.

However, staff are more aware of the benefits of taking care of self- a consequence of embedding mental health in HAART’s workplace culture. Morale is higher, productivity is greater. Decision-making is easier. Knowing that the work requires quick response and that those responses impact the lives of survivors, staff report they are able to make decisions with more clarity and confidence. All of that matters, not just for staff but for all those they work with. And that is why HAART continues to prioritize mental health, for as they frequently remind each other, “You cannot give from an empty cup.”

To learn more about HAART’s work to empower survivors of labor trafficking in Kenya, supported by GFEMS, click here.To learn more about HAART, click here.

Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.*

Burnout is Real: Practitioners Need Mental Health Support Too

The world is paying more attention to mental health. COVID-19 undoubtedly elevated the conversation as extended lockdowns took their toll on virtually everyone’s mental state. Today, we see advertisements for anti-depression pills and anxiety treatments regularly cross our screens; we hear celebrities talk of managing mental health and sports stars actively promote talk therapy; many doctors accustomed to treating our physical ailments are beginning to inquire about our mental health. The world may be paying more attention, but are we really doing enough to prioritize mental well-being?

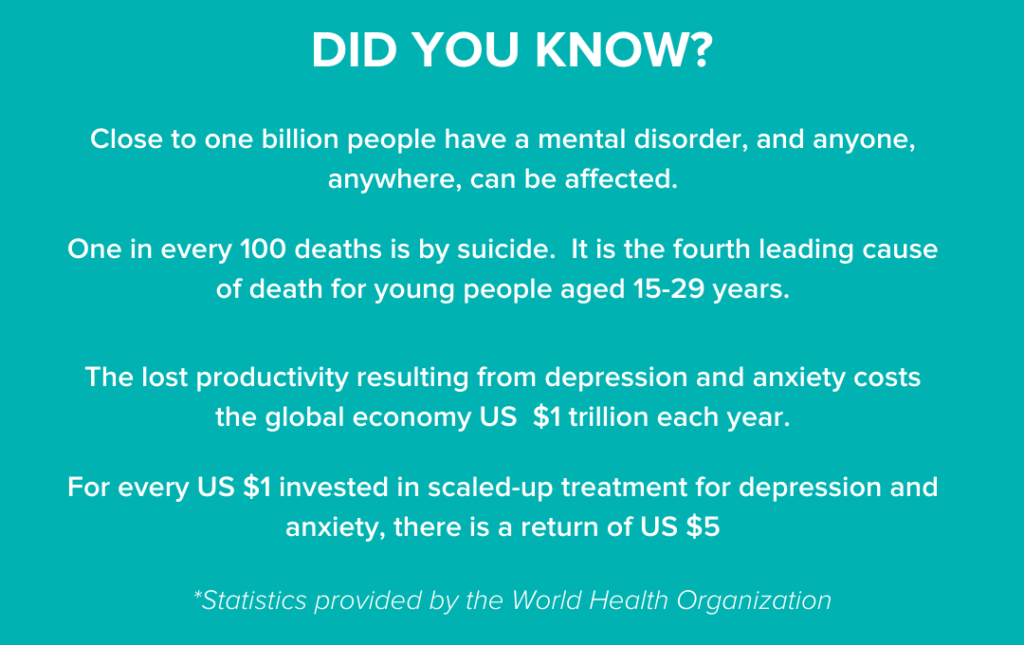

According to the World Health Organization, nearly one billion people have a mental disorder. One BILLION. The cost to the global economy is about $1 trillion each year in lost productivity resulting from depression and anxiety, two of the most common mental disorders. Perhaps even more startling- more than 80% of people experiencing mental health conditions are without any form of quality affordable mental health care.

While mental health disorders can affect anyone anywhere, they are especially common among those confronting and coping with crisis, trauma, or a history of abuse. Those like Farishta– who had gone abroad to earn a better wage as a domestic worker but instead met exploitation and abuse at the hands of her employers. Though Farishta eventually returned to Bangladesh, she did so without the money or savings that was expected. She was shunned by a family and community that branded her a failure. Farishta struggled with thoughts of taking her own life before she was introduced to Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP), a community-based migrant workers’ organization, that helped her heal physically, mentally and emotionally.

For Farishta, mental health services were a critical part of recovery and reintegration. Not only for her but for her family. With both participating in counseling sessions, Farishta was able to reconnect with a son who, after refusing to call her mother, now understood her trauma.

As both practitioners and survivors recognize the importance of mental wellbeing, mental health has become a cornerstone of the modern anti-slavery movement. Indeed, it has to be. Study upon study shows that survivors are more likely to battle depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), even self-harm. We also know that mental health needs, when left unmet, can increase a person’s risk of being trafficked or perpetuate a cycle of victimization.

The call for trauma-informed and survivor-centered care has grown louder in recent years. It’s an approach that guides much of our anti-trafficking programming, supporting survivors to heal in ways that pay mind to the effects of trauma and the experiences of those who live it.

But, even if “the field” is centering mental and emotional well-being, does that mean we are? Mental health may be a central feature of anti-trafficking programs and research, but what about the individuals who are implementing those programs or the researchers conducting the studies? Is mental health a priority? Does it need to be?

Put Your Own Oxygen Mask on First

Its guidance that seems to make more sense when you are 35,000 feet in the air and delivered as part of a flight attendant’s do-or-die safety message, but somehow it feels less applicable when our feet are planted under a desk, our thoughts on programs that support others- even less applicable still when we spend a greater part of everyday working directly with survivors of human trafficking.

As practitioners, we advocate for trauma-informed and survivor-centered approaches to care, and we abide a “do no harm” mantra. We develop guidance and best practices for working with survivors and vulnerable populations and we commit to following them; we share what we know in trainings and convenings and we improve together; and then we monitor and evaluate to make sure what we are doing is working for the people we serve and we try to fix it when it isn’t.

Confronting stories of sexual exploitation, forced labor, and human rights abuse daily, there’s a heaviness about the work we all do. It’s a heaviness that often makes it hard to close the laptop at the end of the day or to ignore that “you have mail” ping first thing in the morning. And for those who engage more directly with survivors, that heaviness can weigh greater.

“Personally, what made me leave direct service work was burnout and the fact that the current system is built on measuring the number of people impacted without thinking about the care of the people actually producing these numbers.

GFEMS is not a direct service provider, but there are some on our team who were. They can attest that “burnout” is in fact very real. One GFEMS staff member recounts how she quite literally witnessed burnout before she herself chose to leave direct service work. “Personally, what made me leave direct service work was burnout and the fact that the current system is built on measuring the number of people impacted without thinking about the care of the people actually producing these numbers. I saw more than three members of my team burnout and have mental breakdown without the system having a process for support.”

So how do we prevent burnout? How do we set up processes for support? How do we continue to do the important and necessary work while still looking after our own mental wellbeing?

It helps when you are part of an organization that takes mental health seriously. And, thanks in no small part to our small and mighty HR team, the Global Fund does. They are our constant reminder that we need to take time for ourselves- advocating for policies like more Administrative Days, peppering our inboxes with self-care tips and words of inspiration, and encouraging us all to use the mental health services and resources the Fund provides.

On a more personal note, we all have activities and people we enjoy. Finding time for them is one of the best things we can do for ourselves, for our work, and for those we seek to support (it’s true, there are studies that say so. See here.) Of course, this looks different for every person.

It may feel selfish to turn your gaze away from the work- even if only for a bit- but ask any new parent how it feels to get a few hours of me-time. It’s reinvigorating, a real game-changer. You tag back in with an energy and enthusiasm to do more and to do it better. It’s good for you. It’s good for them. It’s good for the work.

Or you can ask the former practitioner who burned out and left.

For Mental Health Resources for Human Trafficking Survivors and Allies, see https://www.acf.hhs.gov/

…

The world is paying more attention to mental health. COVID-19 undoubtedly elevated the conversation as extended lockdowns took their toll on virtually everyone’s mental state. Today, we see advertisements for anti-depression pills and anxiety treatments regularly cross our screens; we hear celebrities talk of managing mental health and sports stars actively promote talk therapy; many doctors accustomed to treating our physical ailments are beginning to inquire about our mental health. The world may be paying more attention, but are we really doing enough to prioritize mental well-being?

According to the World Health Organization, nearly one billion people have a mental disorder. One BILLION. The cost to the global economy is about $1 trillion each year in lost productivity resulting from depression and anxiety, two of the most common mental disorders. Perhaps even more startling- more than 80% of people experiencing mental health conditions are without any form of quality affordable mental health care.

While mental health disorders can affect anyone anywhere, they are especially common among those confronting and coping with crisis, trauma, or a history of abuse. Those like Farishta– who had gone abroad to earn a better wage as a domestic worker but instead met exploitation and abuse at the hands of her employers. Though Farishta eventually returned to Bangladesh, she did so without the money or savings that was expected. She was shunned by a family and community that branded her a failure. Farishta struggled with thoughts of taking her own life before she was introduced to Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP), a community-based migrant workers’ organization, that helped her heal physically, mentally and emotionally.

For Farishta, mental health services were a critical part of recovery and reintegration. Not only for her but for her family. With both participating in counseling sessions, Farishta was able to reconnect with a son who, after refusing to call her mother, now understood her trauma.

As both practitioners and survivors recognize the importance of mental wellbeing, mental health has become a cornerstone of the modern anti-slavery movement. Indeed, it has to be. Study upon study shows that survivors are more likely to battle depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), even self-harm. We also know that mental health needs, when left unmet, can increase a person’s risk of being trafficked or perpetuate a cycle of victimization.

The call for trauma-informed and survivor-centered care has grown louder in recent years. It’s an approach that guides much of our anti-trafficking programming, supporting survivors to heal in ways that pay mind to the effects of trauma and the experiences of those who live it.

But, even if “the field” is centering mental and emotional well-being, does that mean we are? Mental health may be a central feature of anti-trafficking programs and research, but what about the individuals who are implementing those programs or the researchers conducting the studies? Is mental health a priority? Does it need to be?

Put Your Own Oxygen Mask on First

Its guidance that seems to make more sense when you are 35,000 feet in the air and delivered as part of a flight attendant’s do-or-die safety message, but somehow it feels less applicable when our feet are planted under a desk, our thoughts on programs that support others- even less applicable still when we spend a greater part of everyday working directly with survivors of human trafficking.

As practitioners, we advocate for trauma-informed and survivor-centered approaches to care, and we abide a “do no harm” mantra. We develop guidance and best practices for working with survivors and vulnerable populations and we commit to following them; we share what we know in trainings and convenings and we improve together; and then we monitor and evaluate to make sure what we are doing is working for the people we serve and we try to fix it when it isn’t.

Confronting stories of sexual exploitation, forced labor, and human rights abuse daily, there’s a heaviness about the work we all do. It’s a heaviness that often makes it hard to close the laptop at the end of the day or to ignore that “you have mail” ping first thing in the morning. And for those who engage more directly with survivors, that heaviness can weigh greater.

GFEMS is not a direct service provider, but there are some on our team who were. They can attest that “burnout” is in fact very real. One GFEMS staff member recounts how she quite literally witnessed burnout before she herself chose to leave direct service work. “Personally, what made me leave direct service work was burnout and the fact that the current system is built on measuring the number of people impacted without thinking about the care of the people actually producing these numbers. I saw more than three members of my team burnout and have mental breakdown without the system having a process for support.”

So how do we prevent burnout? How do we set up processes for support? How do we continue to do the important and necessary work while still looking after our own mental wellbeing?

It helps when you are part of an organization that takes mental health seriously. And, thanks in no small part to our small and mighty HR team, the Global Fund does. They are our constant reminder that we need to take time for ourselves- advocating for policies like more Administrative Days, peppering our inboxes with self-care tips and words of inspiration, and encouraging us all to use the mental health services and resources the Fund provides.

On a more personal note, we all have activities and people we enjoy. Finding time for them is one of the best things we can do for ourselves, for our work, and for those we seek to support (it’s true, there are studies that say so. See here.) Of course, this looks different for every person.

It may feel selfish to turn your gaze away from the work- even if only for a bit- but ask any new parent how it feels to get a few hours of me-time. It’s reinvigorating, a real game-changer. You tag back in with an energy and enthusiasm to do more and to do it better. It’s good for you. It’s good for them. It’s good for the work.

Or you can ask the former practitioner who burned out and left.

For Mental Health Resources for Human Trafficking Survivors and Allies, see https://www.acf.hhs.gov/

…The impact of COVID-19 on apparel workers in Bangladesh has been devastating, but the pandemic did not create worker vulnerabilities.

COVID Revealed Just How Vulnerable Apparel Workers Are. Now What Do We Do About It?

Bangladesh has long been an epicenter for apparel production. Its garment industry is the second-largest in the world, behind only China. It accounts for about 84% of Bangladesh’s export revenue, and readymade garments account for almost 16% of the country’s GDP. It is home to some 4,000 factories and employs more than 4 million people. 4 out of five of these workers are women.

The cost of labor in Bangladesh apparel factories remains low, among the lowest by global standards. The Bangladeshi government raised the minimum wage for garment workers to 8,000 Tk or $95 USD per month in December 2018, the first increase in 5 years. In response, in January 2019, protestors took to the streets. Workers claimed the increase did not reflect the rising costs of living, and questioned how they were to sustain families and households on poverty wages.

Then, in 2020, a global pandemic hit.

At least $3 billion of orders were cancelled. More than 1 million workers- mostly women- were laid off or furloughed, representing a quarter of the workforce. Overseas apparel sales fell 18%. Recent data shows that fashion owes $16 billion in outstanding payments.

The numbers are stark, but what’s behind the numbers is even starker. For those working in Bangladesh’s apparel factories, especially those laboring in the informal economy to produce the “made in Bangladesh” tag, these numbers mean a very grim reality.

They mean that millions living on the margins were suddenly without an income. Most had little or no savings. And many were denied the legally mandated severance benefits to provide any cushion. Workers like Mr. Ali, a knit operator for 17 years owed over $4,000 USD in severance pay, hold out hope that “the money will come” but are so desperate to feed their families that they have contemplated suicide.

They mean that there are more children- school age boys and girls, some not yet 10 years old- in Bangladesh’s apparel factories, working to keep their families afloat.

COVID-19 is not the root cause of vulnerability but it has shown the world just how vulnerable apparel workers are.

They mean that expecting mothers and older workers are being terminated first because employers do not want to or cannot pay the benefits to which they are entitled.

They mean workers are putting up with more abuse in the workplace because they fear losing their jobs and their only source of income. Women workers, in particular, are reporting increased sexual harassment and verbal abuse.

They mean that, in some of the most vulnerable communities, 95% of households have less than a week of food supplies, and barely 3% are receiving any government aid. Mothers who work long days at the factory are undernourished, going without so that their children can eat.

The impact of COVID-19 on apparel workers in Bangladesh has been devastating, but the pandemic did not create worker vulnerabilities. Those laboring on the factory floor, under exploitative conditions for up to 12 hours a day, do so because they have few other employment options. They are often young, unskilled, and frequently women and migrants. They are vulnerable to forced labor due to poverty, the fragmented, informal nature of textile supply chains, and the lack of enforcement of legal protections for workers. COVID-19 is not the root cause of vulnerability, but it has shown the world just how vulnerable apparel workers are.

Informal Factories Operate in the Shadows, Leaving Workers Vulnerable

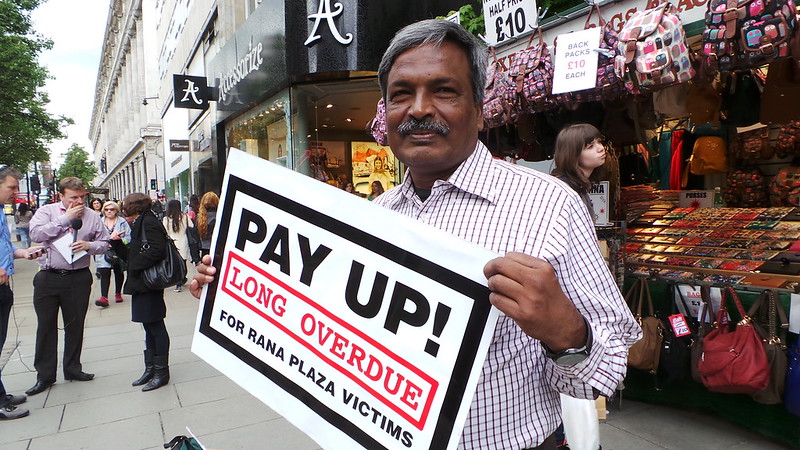

Since the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, when more than 1,100 people died in a garment factory collapse, labor standards have improved, at least in Bangladesh’s formal factories. Evidence shows better working conditions, more factory inspections and greater accountability. But, for those working in informal factories, the risks of exploitation remain high.

“The informal economy is characterized by one central feature: it is unregulated by the institutions of society, in a legal and social environment in which similar activities are regulated.” In other words, there is little government or corporate oversight, meaning factory owners often have limited awareness or knowledge about labor laws; they operate with little consequence for violating laws and little support to improve working conditions.

Some of the worst labor practices are clustered in the informal economy. Informality is associated with lower and less regular incomes, inadequate and unsafe working conditions, extreme job precarity and exclusion from social security schemes, among other factors. A recent study estimates that as many as 3 million Bangladesh workers producing ready-made garments (RMGs) fall outside the scope of any labor monitoring programs.

Worker Survey Gives Voice to Hidden Workers

To give voice to these invisible workers and increase transparency in the RMG sector, we partnered with ELEVATE to deploy a worker survey in Keraniganj and Narayanganj, two of Bangladesh’s key informal apparel production hubs. A relatively low-tech tool, the survey does not require a respondent to be literate or even own a smartphone. Rather, workers anonymously answer a series of multiple-choice questions by pressing a number on their mobile phone’s keypad using voice response technology. During the weeks after responding to the survey, workers then received a series of informational/educational messages informing them of their rights. In instances where child labor or risk of forced labor was identified, referral operators followed-up to link workers to support services such as skills building activities and/or education. While giving voice to a hidden population, this project not only identified exploitation in informal apparel factories, but supported workers to remove from exploitative conditions.

The Results:

The results of the worker survey revealed high rates of child labor –higher than expected and much higher compared to the formal sector. Poverty, exacerbated by the pandemic, pushed most children into factory jobs. Nearly 9 out of 10 working children reported migrating to the cities for work in the informal sector to be able to support their families’ income. Most of these children live in the nearby slums within walking distance of their workplace. Most had never attended school or were forced to drop out. Children are especially vulnerable to exploitation. Anecdotal evidence shows that employers prefer to engage children because they are more easily convinced to work longer hours for less money. Many children are unaware of their rights and thus less likely to protest when those rights are violated.

Follow-Up:

What to do with these findings? With the Fund’s support, ELEVATE partnered with three local organizations to provide educational and support services to identified victims of child labor. Each of these three organizations- Bangladesh Labour Foundation (BLF), LEEDO, and Community Participation and Development (CPD) – have experience in these two high-risk areas and in implementing educational programs. Each adapted their curriculum and program offerings in response to student needs.

BLF, for example, amended its traditional curriculum to include Bangla language, mathematics, and English, as these were the courses that young workers most requested. CPD, focused on building technical and vocational skills, enabled students to select a program based on their needs and interest. While some preferred to hone skills relevant to the garment industry, others, especially the younger students, were most interested in learning generic trades to improve their future employability and personal self-development. LEEDO, an organization that runs informal schools for street children, primarily targeted children under the age of 14, complementing their curriculum with recreational activities such as Carom Board, Ludo, and gaming.

Of the children who attended these schools, some have left the factory. They have returned to their villages and enrolled in school. Yeasin*, just 9 years old when his father’s injury forced him to quit school and start working, found time to attend one of BLF’s programs in between work shifts. Finding Yeasin eager to exit the factory and continue studying, BLF reached out to his father. Yeasin returned to his family and is now enrolled in the government school in his village.

Other children have moved on to better jobs or better wages. 14-year old Joshin* left school to work in a garment factory after COVID-19 pushed his family into financial crisis. For his labor, he was provided three meals a day, but no wages. After studying English, Bengali, and mathematics as a student in LEEDO’s School under the Sky program- courses that helped him excel in his daily work- Joshin found work in another factory. In his new position, Joshin earns wages that are helping support his family. He expects to earn a promotion soon.

Education is only part of the solution. Reducing vulnerability means changing systems

Educational programs and skills training play an important role in providing children an alternative to working in informal factories, but they are not the solution. Nor is any one program. To ensure children are kept out of factories, we need to address whole systems. This means engaging governments to legislate and enforce labor reform; engaging businesses to change exploitative labor practices; raising awareness to prevent child exploitation; enhancing access to social protection benefits to build financial security; and creating sustainable livelihood options so that mothers, fathers, boys, and girls are not forced into exploitative working conditions.

The Global Fund supports numerous projects to reduce forced and child labor in Bangladesh’s informal factories. In addition to the worker voice survey and the educational programs that resulted, we support research to identify gaps in existing legislation and we recommend specific actions for policy and law enforcement groups, government officials, and brand representatives to take to end forced labor. We invest in the development of innovative tools to help brands, buyers, and suppliers prevent, detect, and remediate forced labor in their operations. The Fair Capacity Platform, for example, helps businesses plan their production capacity better, reducing the probability that they resort to subcontracting or excessive overtime to meet unrealistic order deadlines.

The garment industry is a central pillar of the Bangladesh economy, and so are the millions of men, women, and children who sustain it. The outbreak of a global pandemic showed the world just how vulnerable these workers are, especially those laboring in the informal sector. It also reinforced our commitment to reducing that vulnerability.

If you are interested in partnering with us to end forced and child labor in the apparel sector, please reach out.

*Names in this blog have been changed to protect identities. The legal age of employment in Bangladesh is 14.

Apparel I Bangladesh

Lessons Learned

During follow-up, many children said they couldn’t afford to quit their jobs, or even reduce their workload to participate in the educational programs being offered, despite expressing interest. For some children, engaging in part-time learning could compromise the source of income that their families depend on. Based on findings from the worker voice survey and real-time feedback from children whom the survey engaged, ELEVATE developed the following guidance for governments, donors, civil society, or private sector actors:

- Efforts to provide education or remediation services to working children must assume that children will not or cannot immediately leave their jobs and should accommodate their work schedules (e.g. by offering part-time courses)

- Educational and support services should offer income-replacement stipends or allowances and provision of social safety net services to convince children and their families to enroll in the programs, and eventually transition into the mainstream education system.

- Referral services should target working children as well as their families. Lack of awareness regarding the negative effects of child labor contributes to decisions that put children in factories.

- Programs aimed at reducing child labor should engage other actors such as factory owners, trade union leaders, and the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishment to eliminate child labor.

Cross Industry Collaboration Against Trafficking: CIDI Initiative gains steam

Cross Industry Collaboration Against Trafficking: CIDI Initiative gains steam

Before the onset of COVID-19, GFEMS and its partners at The Knoble and SAS Institute were scheduled to host a Cross Industry Data View workshop, building on the work of the Liechtenstein Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking (FAST) Initiative. The workshop, acting as a platform to explore opportunities accelerating progress in financial sector mobilization, was intended to be the starting point for building a roadmap to a cross-industry data view of financial transactions. Such a data view could enable financial institutions to better identify and track illicit financial flows.

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the workshop was taken online in the form of a webinar, and interest in the project has gained momentum. Since the Initiative launched in May, more than 130 participants from over 60 organizations across government, financial institutions, fintech, and NGOs are working together virtually to identify actionable steps to facilitate better data gathering and sharing and paths for collaboration between public, private, and nonprofit sectors. Contributing their expertise to the Initiative across five working groups, Data, Law Enforcement and Regulations, Role of the NGOs, Scams and Abuse, and Ideation, CIDI participants have dedicated over 1200 hours to the project.

Shawn Holtzclaw, Acting Executive Director of The Knoble and leader of the Ideation working group, said, “We are facing a challenge that requires collaboration, ingenuity and determination. Through CIDI I am confident we’ll begin to create systemic impact.”

The CIDI initiative was created to address the need for improved partnership in data sharing by financial institutions to improve visibility into illicit financial flows. Financial institutions have different views of transactional and account activity, resulting in only partial or fragmented understandings of potentially illicit financial flows. There is an opportunity to create a more holistic picture of account activity through improved collaboration and communication between financial institutions and by developing a cross-industry data view that utilizes pre-existing infrastructures and capabilities within the financial sector. Ultimately, this improved data view has the potential to accelerate efforts to identify and disrupt illicit financial flows to traffickers.

The CIDI working groups will continue to meet throughout this quarter, each working on specific proposals and identifying needs and opportunities to advance the goals of the Initiative. GFEMS looks forward to continuing this work and sharing our results and findings into the future.

To learn more about the CIDI initiative or the Fund’s partnership with The Knoble, please visit our website, follow us on Twitter and subscribe to our newsletter.

Fostering Financial Sector Collaboration to End Modern Slavery

Fostering Financial Sector Collaboration to End Modern Slavery

This month the Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) is co-hosting a Cross-Industry Data View webinar in partnership with The Knoble and SAS Institute. The webinar will cover the work to-date of the Liechtenstein Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking (FAST) Initiative and explore specific opportunities to accelerate progress. This will be followed by an in-person workshop later this year where participants will build a roadmap for creating a cross-industry data view of financial transactions.

These expert convenings are part of the Fund’s ongoing commitment to mobilizing the financial sector against trafficking and slavery, following the launch of the Liechtenstein Initiative’s Blueprint for Mobilizing Finance Against Trafficking and Slavery at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2019. In alignment with the Fund’s approach, the workshop will foster collaboration across sectors by bringing together representatives from financial institutions, government, anti-trafficking organizations, and the FAST Initiative.

Financial institutions have different views of transactional and account activity, resulting in only partial or fragmented understandings of potentially illicit financial flows. There is an opportunity to create a more holistic picture of account activity through improved collaboration and communication between financial institutions. It may be possible to develop a cross-industry data view by utilizing pre-existing infrastructures and capabilities within the financial sector. Ultimately, this could accelerate efforts to identify and disrupt illicit financial flows to traffickers.

In the upcoming workshop, GFEMS and its partners will work side by side to identify actionable steps for creating this data view to enable institutions to proactively share relevant information. Participants will focus on identifying opportunities to improve information sharing across institutions, clarify what information needs to be shared, and pinpoint outstanding challenges to be addressed. Following the workshop, participants will develop a project roadmap that includes clear steps and milestones to creating a cross-industry data view.

GFEMS thanks The Knoble and SAS Institute for their partnership and looks forward to continued collaboration with the financial sector as part of its overarching strategy to end modern slavery by making it economically unprofitable.

Read more from GFEMS on mobilizing the financial sector to end modern slavery and human trafficking.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter for the latest information on our activity.

==

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) is a bold international fund catalyzing a coherent global strategy to end human trafficking by making it economically unprofitable. With leadership from government and the private sector around the world, the Fund is escalating resources, designing public-private partnerships, funding new tools and methods for sustainable solutions, and assessing impact to better equip our partners to scale and replicate solutions in new geographies.

GFEMS Launches “Future in Training — Hospitality” Survivor Employability Pilot

GFEMS Launches “Future in Training — Hospitality” Survivor Employability Pilot

A major theme in the recommendations from the 2019 U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking’s Report is the need for additional resources dedicated to assistance in gaining and maintaining employment for underserved populations like survivors of human trafficking. While lack of specialized employment support is not a new problem and similar recommendations have been made in the past, few resources exist for survivors to gain the necessary skills or training to succeed in obtaining meaningful and decent work.

This International Women’s Day, GFEMS is pleased to announce the pilot launch of the “Future in Training (FIT) Hospitality” Survivor Employability Curriculum, in partnership with Marriott International.

Developed by GFEMS and Marriott over the past two years, the first-ever FIT curriculum focuses on hospitality. It is the Fund’s first program in the United States and is aimed specifically at providing training and resources for survivors seeking careers in the hospitality sector. Marriott’s partnership with GFEMS is part of the company’s human rights goals, which include training 100% of on-property hotel workers in human trafficking awareness. To date, the company has trained over 700,000 hotel workers,

The FIT Hospitality pilot will be implemented with the support of the University of Maryland Safe Center (UMD Safe Center) in the Washington, DC metro area. Through this program, GFEMS will provide survivors with an introduction to hospitality and tools for employability in the sector using a multi-disciplinary curriculum encouraging dynamic engagement. The first-phase of the pilot will test implementation and knowledge gained to inform further enhancements and the need for post-curriculum follow-up services, such as application assistance or career mentoring. Pilot participants will also benefit from transportation and child care support that mitigate known barriers to survivor career training.

GFEMS anticipates several learning outcomes following the FIT Hospitality pilot. GFEMS will support identification and monitoring of the barriers survivors face in trying to gain training and aim to understand the adequate level of support survivors need while participating. Ultimately, GFEMS seeks to gain a better understanding of the type of assistance survivors need to gain meaningful employment and implement that knowledge into the FIT curriculum and other programming; the Fund aims to create customized assistance that meets the needs of survivors.

The pilot will provide valuable insights for GFEMS as it continues to build its portfolio within one of its key pillars, Sustaining Freedom for survivors. As GFEMS continues to grow and build new programs globally, livelihood training programs in various industries and sectors that both equip survivors with necessary skills and prevent at-risk populations from entering risky situations remain a priority. Insights from the FIT Hospitality pilot, along with other planned research, will inform new FIT programming in additional sectors for sustained freedom in the US and abroad.

Following the pilot’s implementation, GFEMS looks forward to sharing the insights gained and plans for future implementation. The Fund is grateful for the partnership and support of Marriott and UMD Safe Center, and is excited to continue our commitment to empowering survivors.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter for the latest information on our activity.

==

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) is a bold international fund catalyzing a coherent global strategy to end human trafficking by making it economically unprofitable. With leadership from government and the private sector around the world, the Fund is escalating resources, designing public-private partnerships, funding new tools and methods for sustainable solutions, and assessing impact to better equip our partners to scale and replicate solutions in new geographies.

Reflections on the Past Decade: 10 years of National Human Trafficking Prevention Month

Reflections on the Past Decade: 10 years of National Human Trafficking Prevention Month

A decade after the inaugural National Human Trafficking Prevention Month in the United States, first enacted by President Obama in 2010, the fight against trafficking continues with the goal of ending modern slavery and human trafficking for good.

The landscape of this fight has transformed significantly and in positive ways. Among some of the successes in the US context are the establishment of the survivor-led United States Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, increased funding for anti-trafficking through the creation of the Program to End Modern Slavery (PEMS), and an emerging cohesion around building the evidence base on what works to end trafficking in persons.

Centering the voices of survivors through the U.S. Advisory Council is an especially significant development. At the Fund, one of our top organizational values is to Learn Continuously, striving to seek out the “knowledge and perspectives of others, especially those of whom we seek to serve and empower.” Survivors are consulted in the design of our programs and regular feedback mechanisms will soon be implemented to ensure our funding assists the intended communities. GFEMS views this as a critical element in the achievement of our mission. Expanded efforts by the US Government, such as the Advisory Council, ensure programming is survivor-informed and will help efforts across advocacy and awareness, prevention, and rescue and reintegration to result in more effective, safe, and relevant interventions.

In its most recent report, the Advisory Council recommended four areas of necessary action:

- Increasing awareness of survivor- and trauma-informed practices among U.S. government staff.

- Building and supporting networks of survivors to provide training, technical assistance, and capacity building to U.S. government agencies and their grantees.

- Increaing public awareness of all forms of human trafficking, including labor trafficking.

- Expanding grantmaking efforts that address all forms of human trafficking and offer services and protection for all victims/survivors no matter their age, gender, creed, race, or sexual orientation.

While GFEMS does not currently implement programs in the US, we have integrated these recommendations– along with suggestions from other survivor-led alliances– into our operations. Our programs, including some funded by the PEMS program, are equipping institutional stakeholders to provide survivor- and trauma-informed care. Our partners must demonstrate how survivor input informs their project and share how survivor-leaders will be empowered through their activities. The Fund’s programs go beyond raising awareness to targeted behavior-change communications. Similarly, the Fund’s portfolio of grants span a diverse group of subrecipients to ensure varied demographics and types of trafficking are addressed.

The PEMS program, of which GFEMS was the first award recipient, represents a significant effort by the U.S. Government to expand grantmaking efforts that address all forms of trafficking. Under its PEMS award, the Fund launched programs across Rule of Law, Business Engagement, and Sustained Freedom for survivors. These programs are a new opportunity to build transformative programs and dig deep into the drivers of modern slavery in multiple sectors and geographies, discovering what really works to end modern slavery sustainably. These resources have allowed GFEMS to develop and test solutions with partners– as well as invest in evidence and learning– to address different parts of the systems perpetuating modern slavery.

While there is still a lot to achieve, the progress the anti-TIP community has made over the past decade are steps in the right direction. Organizations are finally, and rightfully, amplifying survivor voices. Stakeholders, including GFEMS, are working collaboratively together to fill the evidence gaps in the field. This shift in emphasis to gathering actionable, rigorous, and accurate data will lead to improved interventions for GFEMS, as well as the field at large, and improve evidence-informed policy at the government level.

Over the next decade, GFEMS looks forward to building on the momentum of progress made thus far, investing in transformative programs to reduce the prevalence of slavery, and working in partnership with others to make slavery economically unprofitable.