It’s not just another day at the office.

You Cannot Give from an Empty Cup: How One Anti-Trafficking Organization Centers Mental Health

This post is co-authored with staff from Awareness Against Human Trafficking (HAART).

It’s Thursday at 3 pm.

Like every Thursday afternoon, staff gather in a small conference room in Nairobi’s city center. Their casual chatter fades as the session’s facilitator enters. She smiles before she opens with her familiar greeting, “So, how do you feel?”

This meeting between staff and therapist has been a routine part of the HAART workweek for the last one year. Though not required, staff from all departments regularly attend. There is no formal structure or predetermined agenda. Rather, the sessions are just a way of checking in with staff, of making sure that they are ok.

The Global Fund may not be a direct service provider, but our partner Awareness Against Human Trafficking -HAART is. They have been supporting survivors of human trafficking in Kenya for over a decade- from basic needs support to psychosocial counseling to economic empowerment activities.

They work daily with girls, boys, men and women who have been abused or exploited and who are working to overcome that trauma. It’s rewarding and necessary work, for sure. But it can take a toll, and that toll can be greater than any even realize. As one member of the HAART team recalls, “I did not know I was experiencing secondary trauma, until during one of our debriefing sessions that I noticed I showed symptoms similar to those of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

While those who work directly with survivors understand the significance of mental health services for survivors, most give far less attention to their own mental wellbeing.

The daily stresses of the job are commonly overshadowed by the mission. For example, as HAART staff attest, direct service work is filled with uncertainties. “One-minute a survivor is okay, the next they are having suicidal ideation. You never know when you will receive a call for a rescue.” There is comfort in predictability. And uncertainty, especially when it is a constant, can create anxiety. But treating that anxiety is rarely top of mind when a survivor in your program is battling suicidal thoughts.

That anxiety is often exacerbated by an organization’s own limitations. There is only so much any one can do. HAART works with survivors to understand their needs and then tries to balance that with what the organization can provide.

While HAART provides counseling, training, economic assistance, school fees, health services, and legal aid to survivors, funds for victim assistance are very limited.

Staff often have to prioritize what kind of assistance to provide despite wanting to do more. And that too can be draining.

When these are your typical workday challenges- when hearing trafficking experiences recounted and watching the struggles of recovery is “just another day at the office,” mental health support must similarly be part of the job. At HAART, it is.

It’s quite admirable really to see how much emphasis HAART puts on staff mental wellbeing. Several years ago, after realizing that staff burnout was not tied to case load but to the nature of the work, HAART committed to doing more to make sure its staff were taking care of themselves, mentally and emotionally. They began small- organizing all staff hiking trips, moving office meetings outdoors, practicing yoga together. And, like all good practitioners, they listened to feedback and adapted to do better.

Since then, HAART has added two full-time mental health professionals to its team.

These professionals engage staff in group sessions, including weekly departmental-level check-ins, and provide one-on-one support for any staff who want it. There is no limit to how many sessions staff can access. Managers too keep regular meetings with their staff. Even when there’s not much to discuss, the check-ins say a lot. The opportunity to chat with a supervisor not just about work but about life helps staff “feel valued.”

Mental health is not just a focus at the top, though advice to take time off and turn off after work hours has certainly helped foster that culture. Staff have their own self-care routines; they journal, they swim, they meditate, some even make dance videos. But what’s more, particularly for the protection team, they each have an accountability partner- a person who holds them accountable for making sure self-care remains a priority.

It’s human life, and that’s a feeling of responsibility that doesn’t end with the work day.

Of course, there are times when even an accountability partner is not enough. And those days when it seems impossible to abide the best-laid guidance for mental wellbeing. As HAART staff are always aware, “it’s human life,” and that’s a feeling of responsibility that doesn’t end with the work day.

However, staff are more aware of the benefits of taking care of self- a consequence of embedding mental health in HAART’s workplace culture. Morale is higher, productivity is greater. Decision-making is easier. Knowing that the work requires quick response and that those responses impact the lives of survivors, staff report they are able to make decisions with more clarity and confidence. All of that matters, not just for staff but for all those they work with. And that is why HAART continues to prioritize mental health, for as they frequently remind each other, “You cannot give from an empty cup.”

To learn more about HAART’s work to empower survivors of labor trafficking in Kenya, supported by GFEMS, click here.To learn more about HAART, click here.

Nearly one-fifth of children in Karamoja believe that migrating is the only way to make enough money to survive.

When Risks are High but Need is Great: Migration and Child Trafficking in Karamoja, Uganda

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery is currently funding the Community Action to End Child Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation project to improve prevention and response to child sex trafficking in Karamoja, Uganda. As part of this project, ICF and the Department of Social Work and Social Administration, Makerere University recently conducted a household survey to measure knowledge, attitudes, and practices around child sex trafficking in the region and to estimate the prevalence of children at risk of and engaged in sex trafficking. The final sample included 986 households (adults) and 830 children aged 12 to 17. For more on research methodology, see our previous post.

**The audio included in this post is a composite narrative; it is based on research findings and does not depict any individual story. It incorporates feedback from the Global Fund’s local partners, Terre des Hommes Netherlands and Dwelling Places, and their project participants.

Karamoja in northeast Uganda is classified as one of the world’s poorest areas. Over sixty percent of its 1.2 million people live in poverty, making Karamoja the least socially and economically developed region in Uganda. In a recent household survey in Napak district, Karamoja, nearly two-thirds of children reported they went to sleep hungry one, two, or three nights in the last week. Indeed, food insecurity remains one of the region’s greatest challenges- one that is intensifying with shifting climate conditions. A study examining changes in the region from 1981 to 2015 found rising temperatures and increasingly erratic rainfall, a trend likely to impose dire consequences in a region where livelihoods –cattle-raising and agriculture- are tied directly to the land.

These same livelihood-sustaining activities have influenced a culture of migration in the region. Groups have long migrated with their livestock to mobile cattle camps, referred to locally as kraals, during the dry season. However, in more recent years, there has been a change in migration patterns. Increasingly, it is children who are leaving Karamoja. Faced with chronic poverty and few options, Karamoja’s youth are leaving to find better opportunities for themselves and their families in Uganda’s urban centers. Indeed, nearly one-fifth of children recently surveyed in Karamoja believe that migrating is the only way to make enough money to survive.

Though many young people consider migration their best or only option, migration presents its own risks. Arriving in cities with no money and no family, migrant children are preyed upon by traffickers eager to exploit this vulnerability. An estimated 90% of children living on the streets or in other vulnerable conditions in Kampala are from Karamoja. Children are exploited in forced begging, domestic work, and commercial sex brothels. Recently, there have been reports of children from Karamoja being sold at markets for 20,000-50,000 UGX ($5.48- $13.70). Among children surveyed in Karamoja, the majority expressed an understanding of the risks associated with migration- many worried they would not make any money, nor have enough food to eat. Others feared they might contract a disease, be beaten, or trafficked for sex. Many children reported that migration brought the risk of being separated from friends and family forever. Yet, despite an awareness of these risks, children from Karamoja continue to migrate.

LISTEN: STORIES FROM KARAMOJA

Adults and children participating in the survey nearly universally agreed in the importance of education, but most children in Karamoja do not regularly attend school. Almost 60% of the children surveyed had not completed primary school while a further 38% of child respondents had no formal schooling at all. The overall literacy rate for the region stands at just 25% (compared to a national average of 68%.)

Evidence shows that girls kept out of school are more likely to bear children at an early age, an outcome with tremendous and long-lasting educational, social, and economic impact. Surveyed boys and girls who reported they had never attended school were significantly more likely to agree that migration is the only way to make enough money to survive. For these children, migration is their only option, no matter the risk.

School is not a priority for many families in the region whose livelihoods are tied to livestock and agriculture. Even as nearly all parents agreed that attending school would enable their children to make more money in the future, parents expect their children will graze cattle and engage in other household-sustaining activities. Almost half of parents surveyed believe that children should begin participating in elejileij or income-generating activities between the ages of 12 and 15. More than 40% of adults believe that it is good for a child under age 18 to migrate in pursuit of food and money.

While expecting their children to earn for the household, parents also expressed an understanding of the risks that migration carries, including children not making any money, not having enough food to eat, contracting a disease, or being beaten. More than half of adults believe that children who leave home often end up being sexually exploited for commercial gain. Although many adults expect children to generate income, either locally or in another town, those surveyed nearly universally agreed that parents must protect their children from people taking advantage of and hurting them. Given that many parents recognize the risks of migration but still think it is good for children to migrate, it may be that they believe that earning experience is key to their long-term ability to avoid harm. Or it may be that, for many, there seems little alternative. The risk of remaining at home is as great as leaving. In other words, people living in extreme deprivation may look for hope elsewhere even when they are aware of risks.

LISTEN: STORIES FROM KARAMOJA

A child’s risk of exploitation is influenced by other factors. In Karamoja, research shows that the relationship between child and caregiver is significant. Children that are ridiculed by caregivers are far more likely to be involved in child sex trafficking that those who are not. More than one third of the children surveyed in Karamoja reported being ridiculed or put down by their caregivers. Having a close friend exploited in sex trafficking also indicates a high level of vulnerability- nearly one-fifth of children surveyed in Karamoja have at least one friend who has been exploited in child sex trafficking. Researchers found that keeping secrets from a caregiver is another significant predictor that a child might be involved in sex trafficking. Significantly, responses showed that caregivers underestimate how often their children keep secrets from them.

Drawing on results of the household survey and children’s and parents’ responses, researchers estimate that one out of every five children in Napak are at high risk of sex trafficking.

LISTEN: STORIES FROM KARAMOJA

The research conducted in Napak district produced alarming results. But it also produced evidence to help us build more targeted interventions. Read more about our programming to combat child sex trafficking in Napak district here.

Research and programs referenced in this article are funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

Protecting Uganda’s children, now and in the future, requires participation and support of the entire community.

“It Takes a Village”: Engaging the Community to End Child Trafficking

In September 2021, our partners in Uganda, Terre des Hommes Netherlands (TdH NL) and Dwelling Places, hosted the first-ever National Dialogue on Child Trafficking. While diplomats, Government leaders, media representatives, and civil society organizations (CSOs) gathered to take stock of Uganda’s collective response to child trafficking, three young girls from Napak District in northeast Uganda joined to raise their voices.

One of these girls, joining virtually and speaking off camera, described the circumstances that led her to leave Karamoja. She had gone to Nairobi to escape hunger at home and earn enough money to pursue the education her parents could not afford. She was also fleeing an impending marriage, forced to enter a union to which she objected. Demonstrating that they were indeed more than their stories of exploitation and survival, these three young girls took the opportunity to press for action.

The girls asked the leaders in attendance to bring their friends- children still being exploited in Nairobi- back home to Uganda. They then requested steps be taken to support children from Karamoja, Napak District to access education. Many children dropped out of school because their parents could not afford the fees. The girls pondered why Karamoja saw so many of its children trafficked and why so many migrated from the region only to end up in child labor, begging, or sexual exploitation.

The State Minister for Disaster Preparedness, the Guest of Honor, offered a response to the girls. She called on the private sector to do its part to end child trafficking and advised civil society organizations to harmonize and coordinate services to ensure all survivors receive the same standard of care and protection. She committed her Ministry to provide food relief for survivors at the Koblin rehabilitation centre in Napak District; and she pledged her advocacy on behalf of education for children in Karamoja. Addressing the girls, she promised the government would do more to end child trafficking.

The following week, in Karamoja, TdH NL facilitated the participation of eight children in the first Annual Stakeholders’ feedback meeting, an opportunity to give feedback on the GFEMS-funded TdH NL project and share their opinions and recommendations. To the Resident District Commissioner, the District Chairperson, the District Education Officer, and other local Government leaders, to the child protection champions, teachers and administrators, and religious and cultural leaders in attendance, the children made several requests. They asked for the continuation of trainings and dialogues on positive parenting to sensitize parents and caregivers on risks of child trafficking. They also requested stricter enforcement of laws against child trafficking, and asked for support and advocacy to change harmful cultural practices and social norms. In addition, they requested more opportunities for their voices to be heard in discussions on how to protect children.

But the children were not done. In one last urgent appeal, they requested that the Government reopen schools immediately. For children in the region, these young advocates explained, schools play a critical role in preventing child trafficking and sexual exploitation. Recognizing the significance of schools in protecting children, the District Education Officer committed to working with local groups to provide access to education until the nation’s schools re-open. Amongst an audience of local officials and decision-makers, these children made their voices heard.

TdH NL and Dwelling Places (TdH NL’s implementing partner) have been working to prevent child sex trafficking in the Napak district of Karamoja and other hot spots in Eastern Uganda since 2014. It is from this experience that TdH NL and Dwelling Places have learned the value and necessity of listening to children most affected by the issue and supporting them to be agents of change in their communities. Indeed, engaging children and youth to combat sexual exploitation and abuse has been and remains a defining feature of TdH NL’s programming, and it may be the most critical. It is part of a comprehensive strategy to protect Karamoja’s children, a strategy that calls the entire community to action to end child trafficking.

A Community at Risk

Karamoja is a young population. The average age is just 15 years old. It is also a growing population. On average, a woman in Karamoja will give birth to eight children, much higher than a national average of five children and soaring above Kampala’s average of three children. With a poverty rate among the highest in the world and a literacy rate of just 25%, Karamoja’s children confront various challenges that put them at increased risk of exploitation.

To reduce these vulnerabilities, TdH NL and Dwelling Places, with funding from the Global Fund, are creating referral, response, and reporting mechanisms to build a “protective shield” for 2,000 children in Karamoja. They are engaging children, parents, teachers, survivors, community leaders, and law enforcement to raise awareness of child trafficking risks, enhance prevention and monitoring, and shift harmful cultural norms. Protecting Karamoja’s children, now and in the future, requires participation and support of the entire community. This is what our partners are working to do.

Building Community Awareness

In the communities of Karamoja, this begins with raising awareness. Community dialogues are at the core of TdH NL’s awareness-raising activities. These are an opportunity for community members to learn more about what makes children susceptible to trafficking or exploitation and what families and the community can do to better protect their children. Building from the findings in a recent Global Fund commissioned study on child sex trafficking, parents are made aware of behaviors and interactions that can negatively affect their children and even contribute to increasing vulnerabilities to trafficking or exploitation. For example, findings show that children who are ridiculed by caregivers are far more likely to be involved in child sex trafficking than those who are not. Among children surveyed in Karamoja, more than one third reported being ridiculed or put down by their caregivers. (See our previous post for more research findings.) For many participants, TdH NL reported, the training was a real “eye-opener”, revealing links between parent-child relationships and trafficking risks. When TdH NL introduced positive parenting messaging, parents were receptive. They pledged to change their behavior and relation to their children, and committed to sharing positive parenting messaging with others in their communities.

Building awareness means educating parents and community members on risk factors for child trafficking and how to reduce those risks. But it also means changing cultural norms that harm children. Girls in particular experience high rates of gender-based violence, fueled by its widespread cultural acceptance in the region. Early marriage or forced marriage is common. Married young, it is more likely a girl will not earn an education, experience poor health, have more children over her lifetime, and earn less in adulthood. In other words, she becomes more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

Boys too suffer the consequences of entrenched gender norms. Traditional perceptions of male masculinity contribute to a culture of repression, silence, and continued exploitation for young boys who fall victim to child trafficking. Findings from a recent Global Fund commissioned study on child trafficking indicate that boys are just as likely to be trafficking victims as girls, but this is a largely unseen and unreported problem. Reluctant to report, boys are unlikely to receive the support they need to recover. Community dialogues explain the harm that such culturally-accepted practices can inflict and encourage participants to rethink practices and customs that put children at risk. Local religious and cultural leaders- community members who hold incredible sway and garner trust in Karamojong villages- are encouraged to lead change.

Significantly, community dialogues are not a one-way conversation. Participants share their experiences and concerns, feedback that is critical to building programs that work best for Karamojong communities. While explaining the challenges that families and children in Karamoja confront, including food insecurity and hunger, raids, unemployment, high dropout rates and low enrollment in schools, forced marriage, and peer pressure, community members also offer insight on what can be done to make their children less vulnerable. In multiple dialogues, for example, participants expressed that children needed more opportunities for education or vocational training. The indefinite closure of schools in response to the pandemic has made children even more vulnerable, a trend that will certainly outlast the outbreak as 30 percent of Ugandan learners are likely never to return to school.

Turning Awareness into Action

While raising awareness of the risks and signs of child trafficking or exploitation is a critical first step in protecting a community’s children, it is not enough. Community members must know how to respond. Information on where and how to report child trafficking is shared during community dialogues, but TdH NL also conducts more targeted outreach. They train teachers and administrators throughout Napak district to monitor for exploitation- for example, to pay attention to attendance and behavior patterns and to take action against it. Most critically, students and youth are engaged to play an active role in prevention, monitoring, and response.

As members of Community Child Rights Clubs (CCRCs), peer support groups facilitated by TdH NL, young Karamojongs learn about their rights and actions that violate them; they are taught about reporting and referring mechanisms; and they are encouraged to share this knowledge with other young people in their communities. Adults, including teachers, serve as club patrons and Child Protection Champions or child advocates supporting the CCRCs. To date, this project has supported the establishment of 35 CCRCs, engaging more than 680 children and youth.

Children, parents, teachers, survivors, village leaders, government officials- the entire community plays a role in preventing child trafficking. With programs informed by on-the-ground research, our partners are engaging the community to protect Karamoja’s children, and they are changing systems to ensure freedom and opportunity for all children.

To learn more about the Global Fund and how you can get involved, click here.

Programs referenced in this article are funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

In supporting young people to develop professional and personal skills and practical experience, the Alliance is empowering young people with greater control over their futures.

Building Skills and a Better Future: How the Hospitality Sector Can Support Survivors to Achieve Sustainable Employment

“Towering above Mumbai’s upscale commercial hub, Four Seasons combines chic modern style with an intimate, boutique atmosphere and panoramic sea views. Let our expert team connect you with local culture, shopping and entertainment. At day’s end, return to our rooftop AER – Bar and Lounge for sunset cocktails and mingling with Mumbai’s elite.”

The website for the Four Seasons Hotel in Mumbai sells an experience of luxury and indulgence, one that appeals to many travellers, both foreign and domestic. But it is not one that youth often imagine themselves a part of, especially youth from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Though many young people may not envision their futures in a five-star hotel, Sustainable Hospitality Alliance (the Alliance) understands the tremendous opportunity that the hospitality industry affords. Unlike many other sectors, the bar for entry into the hospitality sector is not set at education or even job experience. Rather, there is a unique appreciation for self-confidence, on-the-job training and practical skills development that opens the hospitality industry to youth of any background. The Alliance works with hotel members and philanthropic, government, nonprofit, and private sector partners across the globe to connect young people with these opportunities. In helping youth develop skills to advance in the hospitality sector or related professions, the Alliance is reducing youth vulnerability to trafficking and exploitation and supporting young people to achieve financial security and a better future.

In 2020, 1 in 5 youth were not in employment, education or training (NEET). This number continues to rise as the world struggles under the weight of a global pandemic. In many cases, youth were the first let go during economic shutdowns- 1 in 6 are estimated to have lost their jobs since the outbreak began. While one month of being unemployed at age 18-20 can cause a permanent income loss of 2% in the future, poverty, malnutrition and financial insecurity are the consequences youth experience more immediately. Confronting increasingly desperate circumstances, young people are more susceptible to exploitation, abuse, and modern slavery.

Despite the heavy blow that COVID-related travel restrictions and national lockdowns dealt to the industry, hospitality can play a critical role in recovery. It remains an important driver of economic growth and job opportunities, and provides young people the chance to develop skills and experience to ensure sustainable employment, within the industry and beyond. Though GFEMS partnership with the Alliance began in 2018, the devastating effects of COVID have highlighted the significance of the intervention. In supporting young people to develop professional and personal skills and practical experience, the Alliance is building youth resilience and empowering young people with greater control over their futures.

A Partnership to Reduce Youth Vulnerabilities and Support Young Survivors

The Alliance initiated its youth employment program in 2004 to support at-risk youth (ages 18-24), including those from impoverished communities or low-income families, those living with disabilities, survivors of human trafficking, and refugees, to achieve sustainable employment. Viewing hospitality as a solution to the problem of youth unemployment, the Alliance has forged partnerships with over 200 hotels in four countries since it began 15 years ago. To date, over 6,000 young people have graduated from the Alliance’s youth employment program.

GFEMS partnered with the Alliance as part of its anti-trafficking efforts in Vietnam and Maharashtra, India, two regions with high prevalence of sex trafficking. Through this partnership, the Alliance is directly engaging survivors and at-risk individuals in its employment program, and supporting them to develop skills and experience to make them less vulnerable to trafficking and exploitation. While this project is making a difference in the lives of the youth it engages, it is also informing the development of a model to be scaled and replicated across countries and industries.

A Program to Build Survivor Skills and Confidence

The Alliance’s youth employment program begins and ends at partnership. To be successful and sustainable, it needs both hotels to conduct practical training and community organizations to connect young people with the opportunity. To build these partnerships, the Alliance first conducts workshops in the region of operation to introduce representatives of hotels and local nonprofits to the program and share best practices for working with survivors. Participating nonprofit partners, including anti-trafficking organizations and youth shelters, commit to mobilizing survivors and at-risk youth for the program. (Some even travelling to harder-to-reach but high prevalence areas to engage vulnerable youth.) Hotels that join the program agree to provide on-site skills training or apprenticeships for youth who complete initial training.

Once partnerships are established, youth are enrolled and begin one month of “pre-training” focused on soft skills development. Consisting of three modules- Life Skills, English for Hospitality, and Introduction to Hospitality- the employment program curriculum develops core employability skills that are relevant to the hospitality sector. In honing digital skills, building financial literacy, and learning to effectively communicate, students are equipped with skills that transfer to virtually any industry. The program also strengthens confidence and job-readiness, soft skills to set young people on a successful career path.

When core training is completed, students are placed for practical skills training, generally with local hotels. On-site training typically lasts two months. After successful completion, graduates are supported to find employment in the hospitality sector or related fields.

“The training has made me employable and capable to be part of the housekeeping team in a hotel. I am learning how to provide service to guests. This training has prepared me to be confident and speak up. I feel self-motivated, excited, and willing to learn.”

“

Lessons to Build Stronger Programs and Scalable Solutions

Programs are rarely implemented without challenges. Learning from these challenges and adapting to meet them is how we can build effective and sustainable strategies to end trafficking and modern slavery. During the second year of program implementation, circumstances on the ground supported the decision to end the youth employment program in Vietnam. As many of the students enrolled in the Hanoi program came from rural provinces, a change in government policy that shifted support for trafficking survivors to their regions of origin deterred many from traveling to Hanoi. With the decentralization of government support, most survivors chose to remain near family and community networks. Indeed, several of the Alliance’s nonprofit partners reported that their shelters in Hanoi no longer housed any survivors.

Adding to this challenge was an important learning uncovered during the course of program implementation. While encouraging that over sixty per cent of Hanoi graduates did in fact secure full-time employment in the hospitality sector, almost half of those who enrolled in the program did not graduate. The Alliance worked with its local nonprofit partners to understand why students were dropping out of the program at such a high rate. The key finding was that location mattered. Students from rural provinces had trouble adapting in Hanoi. Separated from family and community, they lacked networks of support to fully engage with the program.

Though disheartening, this learning, reinforced by findings from other GFEMS-funded projects in Vietnam, demonstrates the significance of locally-accessible programming and tailoring programs to match survivor needs. The Alliance and GFEMS shifted remaining funding to scale up programming in India, but the Hanoi program should not be counted a loss. From this knowledge, the Alliance and GFEMS are building stronger programs, programs that take account of local circumstances and survivor needs, programs that can be scaled-up effectively within the hotel industry and replicated across sectors.

Challenges to program implementation were not confined to Hanoi. Like the rest of the world, the Alliance experienced the disruptions wrought by a global health crisis and national lockdowns. The hospitality industry was especially hard hit. Many hotels and restaurants were forced to shutter their doors and others froze new hiring, making new placements all but impossible. The Alliance also had to suspend in-person soft skills trainings indefinitely.

While no one could have predicted a global pandemic, the Alliance worked quickly to mitigate its impact on the project and more importantly, on the young people it supported. Almost immediately, the Alliance began outreach to students engaged in the employment program. These young people were provided mental health and professional counselling through one-on-one calls with trained staff from Alliance’s local partner, Kherwadi.

Moreover, the Alliance very quickly transitioned its soft-skills training to an online format to ensure students could continue learning even during the chaos and uncertainty of COVID. Further adapting to COVID challenges, the Alliance collaborated with GFEMS to find new practical skills training opportunities. Identifying industries where students’ soft skills readily transferred and where students could still gain relevant experience, the Alliance began offering placements in healthcare, food & beverage, housekeeping, and customer service. Though some students opted to defer placement until positions could be secured in the hospitality sector, many others readily engaged with these opportunities. Despite the disruptions caused by COVID, 68% of students who entered the Mumbai program in summer 2020 graduated by spring 2021. 74% had secured employment before leaving the program.

The Alliance’s youth employment program in Mumbai continues to thrive. The success of the program inspired two additional nonprofit organizations to partner with the Alliance last quarter to mobilize more students. Drop-out rates have steadily declined and students are increasingly asserting more agency in decisions about their futures. Placements may be taking a bit longer now, but it is no longer because of COVID. With enhanced knowledge and confidence, students are more aware of their options and waiting for the right employment opportunity.

“The training program has helped me to be a courageous and independent individual. I have a strong feeling that the things that I have learned in this training will help me to work towards building my career. I wish to work and make it to a higher position in a top-tiered hotel.”

.

In June, the Alliance publicly launched the curriculum that lies at the heart of its youth employment program. The core employability curriculum, developed with inputs from industry experts and education specialists, is designed to empower youth with relevant and transferable job skills. It is a free resource, for use by community and training organizations around the world. In supporting young people, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, to build skills and confidence, the Alliance is opening sustainable employment pathways, and reducing vulnerability to abuse and exploitation.

Programs referenced in this article are funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

Trauma-informed care is critical to the wellbeing of survivors of trafficking.

From Repatriation to Reintegration: Centering Survivors to Effect Systemic Change

Every year, approximately 50,000 girls and women are trafficked to India across Bangladesh’s western border. In India, they are forced to labor, sold into prostitution, or trafficked out to be exploited and abused in another country. Around 500,000 Bangladeshi women and children from 12-30 years old have been illegally trafficked to India in the last decade.

Despite a common understanding of the problem, efforts to eradicate trafficking and repatriate victims of modern slavery are failing thousands of women and girls. Communities in Bangladesh’s Khulna Division have proven especially vulnerable to trafficking. Situated at the border with India, Khulna Division is already a high-risk community with overpopulation, extreme poverty, and remoteness of location exacerbating these risks. Criminals are only emboldened by extremely low conviction rates for trafficking cases. Even when trafficking victims are identified in India, they languish in shelter homes for years before they are able to return home.

When survivors return to Bangladesh, they remain susceptible to re-trafficking. They are often ostracized by their communities or burdened with a social stigma that hinders recovery and reintegration efforts. These challenges, combined with a lack of employment and educational opportunities, leave survivors vulnerable to further exploitation. In a recent study, our implementing partner in Bangladesh found that 30% of the survivors they currently support had been trafficked multiple times before.

As has been seen across the globe, COVID-19 takes its heaviest toll on those who are the most vulnerable. In Bangladesh’s Khulna Division, there has been no exception. According to the US State Department’s most recent TIP Report, increasingly widespread job loss, wage cuts, and poverty in Bangladesh’s rural areas and urban slums due to the pandemic has forced some children into begging and commercial sex. In 2020, NGOs in Bangladesh reported traffickers lured victims with promises of “COVID-19 free” locations.

Justice and Care, an international nonprofit, has been supporting survivors, pursuing justice, and securing at-risk communities for over a decade. In partnership with GFEMS, Justice and Care is implementing programming in Bangladesh’s Khulna Division to provide trauma-informed and survivor-centric care, train border guards and law enforcement officials to identify and respond to cases of human trafficking, and build the capacity of government and aftercare service providers. In other words, we are working together to provide end-to-end support for survivors and to change the systems that enable human trafficking.

A holistic care model

Trafficking can take many forms and not all individuals experience trauma the same way. While working with governments and institutions to prevent further traumatization through timely and survivor-centric repatriations, Justice and Care remains focused on the individuals that experience trafficking and exploitation. When possible, the same caseworker that is introduced to a survivor in an Indian shelter supports and guides a survivor through repatriation and reintegration in Bangladesh. This individualized pairing helps establish trust between survivor and caseworker and supports a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of a survivor’s needs. In Bangladesh, a survivor is provided immediate shelter and psycho-social counseling while survivor and caseworker together draw up a longer-term individualized care plan.

Justice and Care have helped me in more ways than I can count. My family got grocery when we did not have any food during the lockdown, and I am also getting support in pursuing a case against my trafficker.

Reforming systems to achieve sustainable change

With survivors at the center of all of their programming, Justice and Care works with various stakeholder groups to ensure a coordinated and survivor-centric response to trafficking. Having piloted a successful initiative to train border guards on victim identification and care before partnering with GFEMS, GFEMS support enabled an expansion of this program. Over the last 12 months, more than 200 staff from Border Guards Bangladesh (BGB) have been trained to identify, intercept, and refer victims of trafficking. As a result, 40 individuals have been intercepted and identified as victims by the BGB at the border and referred to Justice and Care.

Programming does not just target law enforcement, however. Justice and Care works to build the capacities of government stakeholders as well as aftercare service providers on both sides of the border. Supporting survivors even before their return to Bangladesh, Justice and Care is committed to reforming a repatriation process that can strand a survivor in an Indian shelter for up to six years. Victims of trafficking in India, when fortunate enough to escape exploitation and abuse, find that escape is just the first step in a long journey home. A complex and bureaucratic system prolongs the process as judges require survivors to stay in country until testimony is given or Bangladeshi officials stall in confirming a survivor is a Bangladeshi citizen. Survivors must gain approvals from police, border officials, social workers, and local and federal officials before they can be repatriated.

Survivors must be a voice in determining survivor care.

Their individual stories may differ, but survivors share a lived-experience of surviving a certain type of trauma and abuse that is essential to the development of effective trauma-informed survivor care programs. In partnership with GFEMS, Justice and Care conducted a Caregivers’ Empowered training session to prepare survivors for mentorship and counseling roles.

Since October 2020, these champion survivors have conducted mentoring sessions with 44 survivors. While providing information on services and care activities for newly repatriated victims, they also assess peers’ mental and physical health and work to address any challenges that survivors are confronting. In follow-ups with participants, “the recipient survivors reported that they felt the peer mentors had understood their problems perceptively, listened attentively and demonstrated empathy- that they felt better emotionally as a result of the session and all asked for ongoing sessions.”

India and Bangladesh have taken steps to speed up the repatriation process, but survivors still wait 18 to 22 months to return home. With an understanding of the traumatic effects of a prolonged shelter stay, Justice and Care is taking steps to expedite return and ensure survivors are repatriated within 12 months. They have forged partnerships with government officials, government-run institutions, and aftercare providers in India and Bangladesh.

Furthermore, they have convened bilateral repatriation stakeholders including Bangladeshi and Indian Rescue, Recovery, Repatriation, and Integration Task Forces to sensitize them to victim-centric and trauma-informed practices, including timely repatriations. They continue to advocate with the Ministry of Home Affairs to push through the adoption of the Standard Operating Procedures to shorten the timeline for repatriations, enhance cross-border coordination, and center survivors in the process. After a recent meeting with the Bangladeshi Ministry of Home Affairs and U.S. government officials, Justice and Care was invited to provide input into a training manual being developed by the US Department of Justice for law enforcement agencies in Bangladesh. Currently working with 44 referral partners in India including the Rescue, Recovery, Repatriation and Integration Task Force in Pune and West Bengal, UNODC, and the Department of Women and Child Development, Justice and Care is building a network of support that centers survivors from the point of first contact. In strengthening local capacities, they are also ensuring that that support is sustainable and scalable beyond program end.

This spring, Justice and Care hosted a special event for survivors. “Season of Wingspread” brought together 34 survivors to share their experiences and to recognize and celebrate what each had achieved towards stable recovery and reintegration. Until systems change and recovery and reintegration support is no longer needed, Justice and Care remains a model of care to replicate.

Our work with Blue Dragon has successfully raised awareness of trafficking for hundreds of at-risk individuals.

Raising Awareness and Centering Survivors: Anti-Trafficking Programming in Northern Vietnam

Stretching to include Vietnam’s northernmost point, Ha Giang is often referred to as Vietnam’s final frontier. Steeped in rugged mountains and grand landscapes, Ha Giang is an overwhelmingly rural province, and home to a large ethnic minority population. Its long porous border with China makes migration a way of life for many in the region. While high poverty rates and a reliance on low-margin agriculture spur migrants to cross the border, these conditions also leave many vulnerable to trafficking and exploitation. The majority of people trafficked in Vietnam are from regions characterized by high rates of poverty and unemployment; they also disproportionately belong to ethnic minority groups.

In the remote villages of Ha Giang, risks are exacerbated by a general lack of awareness of trafficking across the province. Many respondents of a household survey conducted in the region understood trafficking as something that happened by force, by abduction or threat of violence. But traffickers are not often so bold. Case research in the same province revealed that the majority of trafficking survivors knew their traffickers before they were exploited, underscoring the importance of awareness-raising to anti-trafficking programming.

We partnered with two local civil society organizations, Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation and Sustainable Hospitality Alliance (the Alliance), to implement comprehensive anti-trafficking programming in Vietnam, in Ha Giang province and Hanoi respectively. With an understanding of the particular vulnerabilities to trafficking in northern Vietnam, Blue Dragon and the Alliance developed programs that focused on prevention, survivor support, and deterrence. While providing support and resources for vulnerable individuals and communities, together, these programs also target the systems that enable trafficking in persons.

Lured by False Job Offers and Fake Marriages

The Vietnamese government estimates 90% of people trafficked from Vietnam are trafficked into China. Eighty percent are sexually exploited. In an analysis of court records from prosecuted trafficking cases in Vietnam, Blue Dragon found that deception was the most common recruitment strategy employed by traffickers. Over a third were lured by fraudulent job offers, 25% by false relationships, and another 25% by fake offers of marriage to Chinese men. “The main trick,” according to a member of a local NGO, “is ‘cheating or luring’ by pretending to build a relationship with victims gradually. Then traffickers trap victims by inviting them to hang out, go shopping at markets, trips near border areas, etc.” The overwhelming majority of these cases (97%) were for commercial sexual exploitation or forced marriage.

The main trick is ‘cheating or luring’ by pretending to build a relationship with victims gradually. Then traffickers trap victims by inviting them to hang out, go shopping at markets, trips near border areas, etc.

The More You Know: Raising Awareness of Trafficking Risks

To help raise awareness of the risks of trafficking and ultimately minimize those risks, Blue Dragon conducted a series of events across Ha Giang province, in collaboration with community stakeholders including village leaders, Women’s Union members, commune police officers, teachers and students. While screening at-risk households and providing support to at-risk individuals, Blue Dragon also led village-, community-, and school-based interventions to increase awareness. Each of these interventions explained the risks associated with irregular migration abroad, including sexual exploitation and forced labor. They also warned against actions, such as migrating without a contract or indebtedness before migration, that might increase one’s vulnerability. To raise awareness of support mechanisms should a case of trafficking be suspected, programming included guidance on who to contact and information on the anti-TIP hotline.

While targeted at prevention, these local interventions included a message of deterrence. The same analysis of court data revealed that traffickers commonly operate in the same impoverished and vulnerable communities as those they traffic. When confronting a lack of viable livelihood options, traffickers frequently act opportunistically, looking to escape their own desperate circumstances. By including an emphasis on the severity of the crime and the penalties that it can incur in its programming, Blue Dragon aimed also to deter would-be traffickers.

Raising Awareness, Decreasing Risk of Trafficking

Post-intervention surveys reveal that these efforts are making a difference. Generally, project findings show a positive relationship between being exposed to awareness-raising activities and understanding of trafficking risks and vulnerabilities. At baseline, for example, only 40% of migrant households in Meo Vac (an intervention district) reported migrating for work with a contract. At program end, 64% were more likely to migrate with a contract. Findings also demonstrate a significant rise in awareness of whom to contact with trafficking concerns, including the provincial anti-TIP hotline. At endline, 28% of respondents listed the hotline as a reporting mechanism versus just .04% at baseline. With a better understanding of the risks of trafficking, migrants are less at risk of exploitation.

Findings also demonstrate a significant rise in awareness of whom to contact with trafficking concerns, including the provincial anti-TIP hotline. At endline, 28% of respondents listed the hotline as a reporting mechanism versus just .04% at baseline. With a better understanding of the risks of trafficking, migrants are less at risk of exploitation.

A Focus on Survivor Support

Despite the heightened risk of trafficking in Ha Giang province, no trafficking survivors reported receiving reintegration support prior to Blue Dragon’s intervention. Across government, law enforcement agencies, and social service organizations, efforts to identify and provide survivor support remained fragmented, making it difficult for survivors to access needed services and resources. Blue Dragon worked with each of these stakeholders to strengthen channels of coordination and information-sharing and to implement the National Referral Mechanism –a cooperative framework through which trafficking victims are identified and referred for services- at the provincial level. Ha Giang authorities have since referred or directly provided reintegration support to thirty-five trafficking survivors, but the mechanisms put in place will ensure many future survivors receive the resources and support they need.

Beyond enhanced coordination, Blue Dragon supported a training program to better prepare social workers engaging directly with survivors. Commenting on the usefulness of the intervention, one program graduate shared, “We used to attend training on the local policies and regulations relating to trafficking in persons, but this is the first time ever we have been trained on how to work with survivors to support them effectively.”

This is the first time ever we have been trained on how to work with survivors and support them effectively.

Social workers trained through the Blue Dragon program were locally-based. The social workers, as well as the service providers involved in the program, understood the socio-economic conditions in each community and almost all were able to communicate with survivors in their native languages or dialects. While this ensured services were accessible to survivors, the program’s emphasis on survivor-centric support empowered survivors to choose services that best supported their individual needs, whether that be housing, healthcare, or vocational training. When survivors are given agency to determine their own paths forward, their freedom becomes more sustainable. 46 of 52 survivors supported by Blue Dragon were “successfully reintegrated,” meaning their risk of re-trafficking was significantly diminished, they were effectively managing their trauma, and building a sustainable new lifestyle.

The Significance of Survivor-Centric Programming

The Sustainable Hospitality Alliance (the Alliance) program similarly supported survivor reintegration by providing livelihood training, specifically by helping survivors develop skills necessary for work in the hospitality sector. As part of GFEMS anti-trafficking portfolio in northern Vietnam, the Alliance established a training program in Hanoi. Sixty-three percent of those who graduated from the program did in fact secure full-time employment in the hospitality sector. However, almost half of those who enrolled in the program did not graduate. Though disheartening, understanding this dropout rate is critical to building more effective interventions. The majority of students who discontinued the program lacked networks of peer support. Trainees, who were from rural provinces, including Ha Giang, had trouble adapting in Hanoi. This finding, combined with the positive response to Blue Dragon’s locally accessible programming, demonstrates the significance of tailoring programs to meet survivor needs. (From this learning, the Alliance and GFEMS shifted remaining funding to the Alliance’s programming in India.)

We partnered with Blue Dragon and the Alliance to combat trafficking in northern Vietnam. While programming directly impacted hundreds of individuals, many hundreds more will benefit from enhanced community awareness and improved social services. Moreover, lessons learned from these interventions will shape future interventions. From these programs, we can build stronger, more sustainable solutions to end trafficking in persons.

This article and the projects it references were funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of State.

Making Modern Slavery Prevalence Studies Count (Accurately)

Making Modern Slavery Prevalence Studies Count (Accurately)

GFEMS recently funded a prevalence study in Karamoja, Uganda to determine the proportion of children in households (age 12-17) who have been sexually exploited for commercial gain. Although analysis is on-going, the data indicate that the prevalence of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) in Karamoja is gender agnostic. In other words, there is no statistically significant difference between the proportion of boys and girls that have experienced sexual exploitation. This runs counter to conventional thinking in the field of modern slavery (as well as a large body of evidence) that girls are more often victims of CSEC than boys (though researchers acknowledge that less is known about the scope and nature of CSEC among boys).

So why are boys in Karamoja more vulnerable to CSEC? Why do findings in Karamoja seem to contradict those of other studies?

The scope and nature of modern slavery varies greatly by geography and socio-economic context, so one simple answer could be that the region is an outlier. Another consideration is that this is the first study of CSEC in Uganda to use probabilistic sampling. Previous studies have used convenience sampling, meaning that results are not representative of the population. Another possible cause (and the focus of this blog) could be the study’s use of Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (ACASI). This interviewing tool is new to the field of modern slavery prevalence estimation and may address some long-standing challenges related to response accuracy.

While prevalence estimations are critical to understanding the scale and scope of modern slavery, ensuring their accuracy is inherently difficult. Prevalence estimates are derived from large-scale surveys in which social desirability bias (respondents’ conscious and unconscious desire to answer in a socially desirable way) presents a significant challenge. Respondents are asked about their involvement in what are considered culturally taboo and often illegal activities. In the case of this study, we are asking children from conservative, rural communities about sexual acts. The survey inquires on the exchange of sex for money, third party facilitation of sex acts, and sexual violence; concepts which are generally considered inappropriate to discuss with adults, even more so unknown survey enumerators.

While there are no perfect solutions that ensure response accuracy to sensitive questions, ACASI offers an alternative approach to traditional face-to-face interviews (FFI), enabling respondents to share information independently and without having to directly engage with an interviewer. This additional degree of response confidentiality helps to reduce social desirability bias and can ultimately produce better estimates

Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (ACASI): How It Works

The most sensitive questions of the prevalence survey were grouped into a tablet-based, self-administered ACASI module. When the interviewer reaches this module, a tablet and a pair of headphones are given to the child respondent. The interviewer explains how the module will work and that the answers are completely confidential. Following this explanation, the tablet-based software guides the child through an interactive training. The training shows the prompts and images that will be used and explains how to proceed through the module (2). The child must provide responses that show comprehension before proceeding to the module.

Once the module begins, the child hears an audio recording of each question. Potential answers are associated with neutral images on the screen and the child is instructed to select the image that corresponds with his or her answer. The child then clicks on an icon to proceed to the next question (3).

Audio:

Have you done sexual things in exchange for you or someone else receiving anything like money, a place to stay, food, gifts or favors?

Touch the green drum if your answer is “yes.”

Touch the red tree if your answer is “no.”

Audio:

How well do your caregivers know your friends?

Touch the GREEN bowl if they know them “very well.”

Touch the BLUE bowl if they know them “somewhat well.”

Touch the YELLOW bowl if they know them “not very well.”

Touch the RED bowl if they don’t know them at all.

Once the child is finished with the module, he or she hands the headphones and the tablet back to the interviewer, and they continue with the rest of the questionnaire. The interviewer will not be able to access a child’s answers after they are recorded.

ACASI is adapted from the public health field where it’s widely used to gather data on sensitive topics like drug use and sexual risk behavior (4). Several studies indicate that ACASI can serve to reduce social desirability bias in survey responses. For example, a study of injecting drug users (IDU) in Sydney, Australia asked respondents a series of 5 questions relating to injecting and sexual behavior that could induce social desirability bias. These questions were first administered via FFI, then readministered to the same respondents within a week using ACASI. Researchers then measured the extent of discordance (i.e. difference) between the two response sets. The study found that FFI yielded what could be considered more socially desirable responses than ACASI. This includes a statistically significant higher mean age of first injection, a lower prevalence of recent syringe sharing, and a longer duration since the last occurrence of unprotected sex (5). Even more telling is that respondents who reported a history of sex work were more likely than other respondents to provide discordant responses on the duration since last occurrence of unprotected sex (42% vs 25% x2= 4.56, p<0.05).

To our knowledge, this prevalence study is the first time ACASI has been applied to the field of modern slavery, and more research is required to determine if it’s effect on social desireability bias will transfer across fields. However, we suspect that the use of ACASI is a contributing factor to our unique findings. CSEC buyers tend to be male, so in a conservative culture (like Karamojong) where homosexuality is not commonly accepted, there is likely a greater reluctance for boys to admit to sexual exploitation than girls. We believe the use of ACASI helped to mitigate this reluctance, leading to more accurate responses. This, in turn, revealed that CSEC in the region is as commonplace for boys as it is for girls.

Although many challenges remain to ensuring the response accuracy of prevalence studies, ACASI represents a new and promising tool as GFEMS, its research partners, and like-minded organizations continue to expand the boundaries of modern slavery prevalence estimation. We encourage other CSEC and modern slavery researchers to employ ACASI, and if possible, test it experimentally. Doing so can provide us with greater insights into the efficacy of this tool and how to apply it optimally. This, in turn, can ultimately provide us with a more accurate and nuanced understanding of modern slavery and the socio-economic drivers that underpin it.

GFEMS looks forward to continuing to share our learnings with the anti-trafficking community. For updates on this project and others like it, subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.

- This study was conducted by ICF and Makerere University and made possible with funding from the Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (J/TIP) under the Program to End Modern Slavery 2 (PEMS 2).

- These images and prompts are also presented and explained to the child during the interviewer-administered portion of the survey using showcards to ensure that he or she understands how to proceed through the module.

- A small-scale pilot test of children aged 12-17 was conducted to assess developmental appropriateness and the ability to train children to use the instrument, and the social workers from Karamoja provided input into the cultural relevance of the shapes and colors.

- Willis, Gordon B, Alia Al-Tayyib, and Susan Rogers. 2001. “The Use of Touch-Screen ACASI in a High-Risk Population: Implications for Surveys Involving Sensitive Questions.” In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Statistical Association, 6; Falb, K., Tanner, S., Asghar, K. et al. Implementation of Audio-Computer Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) among adolescent girls in humanitarian settings: feasibility, acceptability, and lessons learned. Confl Health 10, 32 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-016-0098-1; Villarroel, Maria A., Charles F. Turner, Elizabeth Eggleston, Alia Al-Tayyib, Susan M. Rogers, Anthony M. Roman, Philip C. Cooley, and Harper Gordek. 2006. “Same-Gender Sex in the United States Impact of T-Acasi on Prevalence Estimates.” Public Opinion Quarterly 70 (2): 166–96.

- M. Mofizul Islam , Libby Topp , Katherine M. Conigrave , Ingrid van Beek , Lisa Maher , Ann White, Craig Rodgers & Carolyn A. Day (2012): The reliability of sensitive information provided by injecting drug users in a clinical setting: Clinician-administered versus audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI), AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 24:12, 1496-1503.

Empowering families and children, GFEMS and Seefar partner to end commercial sexual exploitation

Empowering families and children, GFEMS and Seefar partner to end commercial sexual exploitation

As a part of its work with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), GFEMS is partnering with Seefar and My Choices Foundation (MCF) in India to empower children, families, and communities to end the commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC).

The project is a new investment in the Fund’s sex trafficking portfolio, focusing on addressing the supply side of slavery and reducing risks for most vulnerable individuals, a key pillar in the Fund’s intervention framework. After an extensive period of scoping research and program design, GFEMS identified targeted prevention interventions among children, their families, and local communities at risk of trafficking and CSEC as an opportunity with high potential for impact and replication.

Coupled with other investments within the FCDO partnership, the Fund’s objective in this project is to understand which targeted prevention intervention is the most effective when working with vulnerable communities in West Bengal. The project is centered around implementing a messaging campaign to inform children of the risk of becoming victims of CSEC and reach potential enablers of CSEC in West Bengal.

The project strategically matches Seefar’s proven anti-trafficking expertise in complex environments with MCF’s broad grassroots network and pre-existing trafficking prevention model, the Safe Village Program (SVP). The intervention is a behavior-change campaign with community strengthening activities in West Bengal. The campaign tests the comparative impact of different combinations of activities in empowering vulnerable individuals and communities to recognize, prevent, and respond to trafficking and CSEC. These activities will include: word of mouth/ remote counselling, service mapping and referral pathways, digital media outreach and media engagement, school and community-based outreach, parent outreach, and community outreach to deliver the behavior-change messaging. Messaging provided will focus on the warning signs of CSEC and the realities children may face when moving away from home at an early age for employment or marriage.

Seefar will test the effectiveness of the prevention strategies to understand which method – or combination of methods – is most effective in changing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices among youth, their families, and their communities with regard to risks to CSEC.

GFEMS looks forward to sharing learnings from the behavior change campaign and insights from Seefar’s research. Learn more about the FCDO partnership, the Fund’s portfolio, and scoping research.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn for updates on the latest developments, news, and opportunities with GFEMS.

Focused on sustainability, GFEMS launches seven new projects in India and Bangladesh

Focused on sustainability, GFEMS launches seven new projects in India and Bangladesh

GFEMS is proud to share the launch of a new portfolio of interventions and innovations with our partner, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). The portfolio is expected to total approximately 9M USD.

The FCDO portfolio represents deepening investments in India and Bangladesh, following the inaugural GFEMS portfolio launch in late 2018, and two additional launches with Norad and the US State Dept. Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons earlier this year.

Originally scheduled to launch in spring 2020, all of the projects in this portfolio have been adapted to reflect and respond to new needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Working with our partners on the ground, these projects are now better designed to mitigate exacerbated vulnerability, adjust to remote environments, and contribute to responsible recovery.

“The FCDO portfolio reflects thoughtful, nuanced, and deliberate action to disrupt modern slavery.”

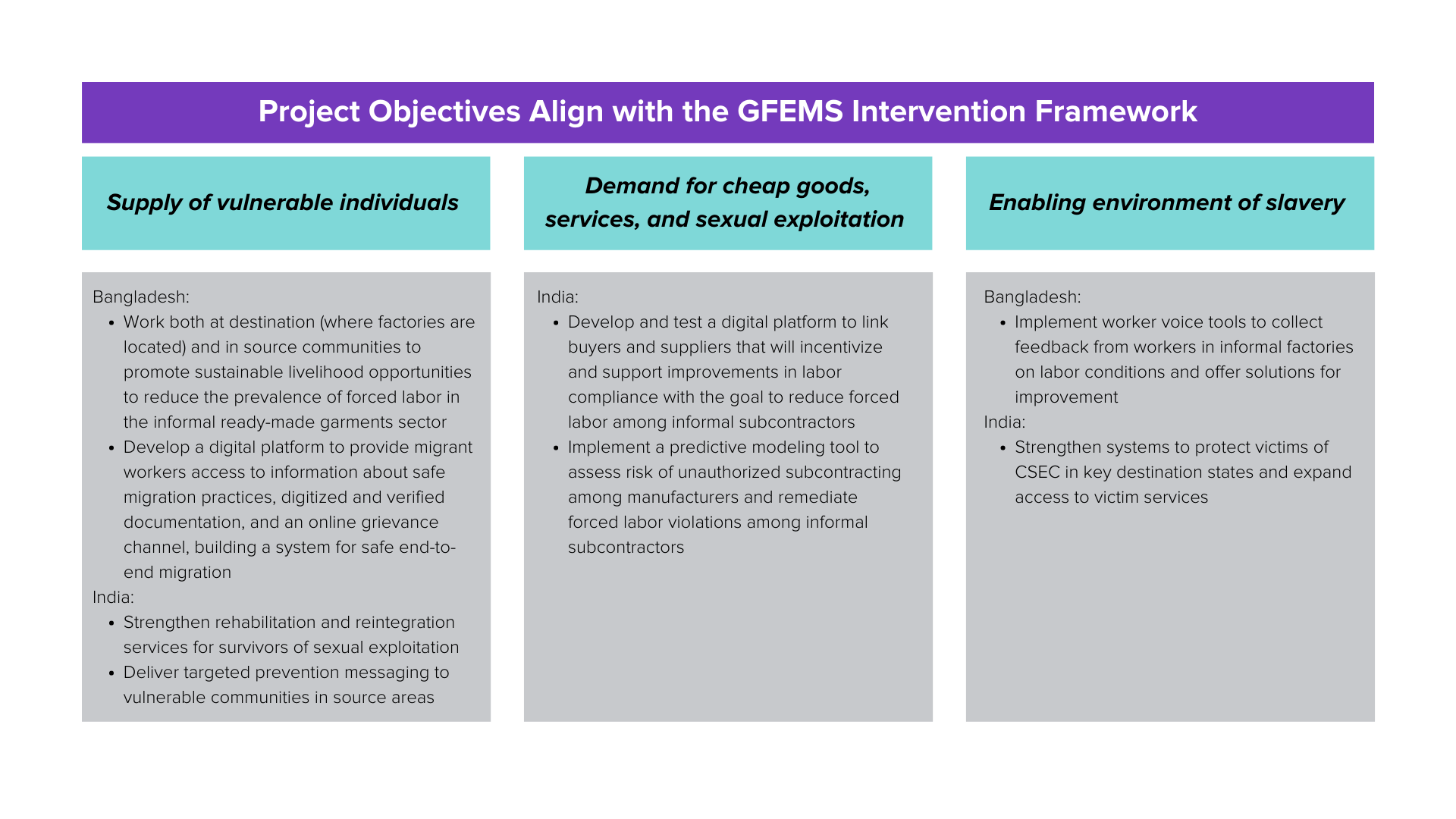

Prior to project launch, GFEMS engaged in extensive scoping and design phases to identify the geographies and sectors with the highest potential for impact. The portfolio, designed based on the findings from that efforts, addresses the following opportunities:

- Overseas Labor Recruitment in Bangladesh

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation (CSE) in India

- Forced Labor in the Apparel Sectors in India and Bangladesh.

GFEMS is funding a total of seven projects across these opportunities:

- IJM– Strengthening Systems to Protect CSEC Victims and Sustain Freedom in Maharashtra

- Seefar– Empowering Children, Families and Communities to End Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children

- BRAC– Reducing Forced labor in Informal Ready-made garment factories in Bangladesh with Sustainable Livelihood Opportunities

- SAI– Improving Buyer-Supplier Engagement, Purchasing Practices, and Capacity/Production Planning India’s Informal Ready-Made Garment Supply Chains

- ELEVATE– Safestep: A Responsible Recruitment Platform for Safe Migration in Bangladesh

- ELEVATE- Laborlink: Disrupting the Prevalence of Forced/Bonded Labor in Bangladesh Informal Ready-Made Garments

- ELEVATE- Developing Predictive Analytics Tools to Disrupt Forced and Bonded Labor in India’s Informal Ready-Made Garments

Projects within the portfolio address the key pillars of the Fund’s intervention framework– supply, demand, and enabling environment of modern slavery. They address core challenges that prevent sustainable reduction in prevalence.

Sustainability is a key theme across the projects, and across the Fund’s wider investment portfolio. GFEMS designs programs and strategies for future investments with sustainability in mind. Funding focuses on both projects with high potential for replication and scale, and those that leverage both national priorities and market demands. All projects are informed by, and tailored to, the populations GFEMS seeks to serve. Within the FCDO partnership, GFEMS specifically targets sustainable changes in supply chain practices, project sustainability through increased government and private sector engagement, and sustainable livelihoods for survivors.

“The FCDO portfolio reflects thoughtful, nuanced, and deliberate action to disrupt modern slavery. The Fund worked closely with partners to develop holistic programming that is based on the best available evidence, but also flexible enough to respond to evolving needs in the field. We are excited to launch these programs with our incredible partners and grateful for the support of FCDO,” said GFEMS Director of Grant Programs, Helen Taylor.

GFEMS will share more information about the portfolio, projects, and our implementing partners in the following weeks. We look forward to sharing the impact, successes, and lessons learned from this portfolio.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn for updates on the latest developments, news, and opportunities with GFEMS.