The impact of COVID-19 on apparel workers in Bangladesh has been devastating, but the pandemic did not create worker vulnerabilities.

COVID Revealed Just How Vulnerable Apparel Workers Are. Now What Do We Do About It?

Bangladesh has long been an epicenter for apparel production. Its garment industry is the second-largest in the world, behind only China. It accounts for about 84% of Bangladesh’s export revenue, and readymade garments account for almost 16% of the country’s GDP. It is home to some 4,000 factories and employs more than 4 million people. 4 out of five of these workers are women.

The cost of labor in Bangladesh apparel factories remains low, among the lowest by global standards. The Bangladeshi government raised the minimum wage for garment workers to 8,000 Tk or $95 USD per month in December 2018, the first increase in 5 years. In response, in January 2019, protestors took to the streets. Workers claimed the increase did not reflect the rising costs of living, and questioned how they were to sustain families and households on poverty wages.

Then, in 2020, a global pandemic hit.

At least $3 billion of orders were cancelled. More than 1 million workers- mostly women- were laid off or furloughed, representing a quarter of the workforce. Overseas apparel sales fell 18%. Recent data shows that fashion owes $16 billion in outstanding payments.

The numbers are stark, but what’s behind the numbers is even starker. For those working in Bangladesh’s apparel factories, especially those laboring in the informal economy to produce the “made in Bangladesh” tag, these numbers mean a very grim reality.

They mean that millions living on the margins were suddenly without an income. Most had little or no savings. And many were denied the legally mandated severance benefits to provide any cushion. Workers like Mr. Ali, a knit operator for 17 years owed over $4,000 USD in severance pay, hold out hope that “the money will come” but are so desperate to feed their families that they have contemplated suicide.

They mean that there are more children- school age boys and girls, some not yet 10 years old- in Bangladesh’s apparel factories, working to keep their families afloat.

COVID-19 is not the root cause of vulnerability but it has shown the world just how vulnerable apparel workers are.

They mean that expecting mothers and older workers are being terminated first because employers do not want to or cannot pay the benefits to which they are entitled.

They mean workers are putting up with more abuse in the workplace because they fear losing their jobs and their only source of income. Women workers, in particular, are reporting increased sexual harassment and verbal abuse.

They mean that, in some of the most vulnerable communities, 95% of households have less than a week of food supplies, and barely 3% are receiving any government aid. Mothers who work long days at the factory are undernourished, going without so that their children can eat.

The impact of COVID-19 on apparel workers in Bangladesh has been devastating, but the pandemic did not create worker vulnerabilities. Those laboring on the factory floor, under exploitative conditions for up to 12 hours a day, do so because they have few other employment options. They are often young, unskilled, and frequently women and migrants. They are vulnerable to forced labor due to poverty, the fragmented, informal nature of textile supply chains, and the lack of enforcement of legal protections for workers. COVID-19 is not the root cause of vulnerability, but it has shown the world just how vulnerable apparel workers are.

Informal Factories Operate in the Shadows, Leaving Workers Vulnerable

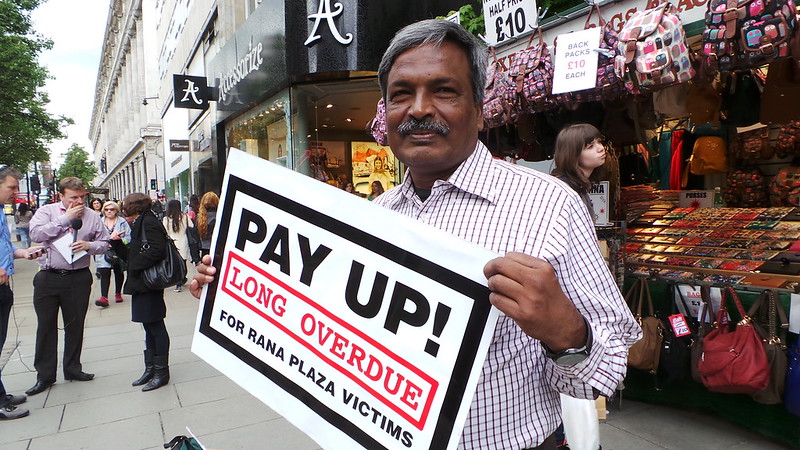

Since the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, when more than 1,100 people died in a garment factory collapse, labor standards have improved, at least in Bangladesh’s formal factories. Evidence shows better working conditions, more factory inspections and greater accountability. But, for those working in informal factories, the risks of exploitation remain high.

“The informal economy is characterized by one central feature: it is unregulated by the institutions of society, in a legal and social environment in which similar activities are regulated.” In other words, there is little government or corporate oversight, meaning factory owners often have limited awareness or knowledge about labor laws; they operate with little consequence for violating laws and little support to improve working conditions.

Some of the worst labor practices are clustered in the informal economy. Informality is associated with lower and less regular incomes, inadequate and unsafe working conditions, extreme job precarity and exclusion from social security schemes, among other factors. A recent study estimates that as many as 3 million Bangladesh workers producing ready-made garments (RMGs) fall outside the scope of any labor monitoring programs.

Worker Survey Gives Voice to Hidden Workers

To give voice to these invisible workers and increase transparency in the RMG sector, we partnered with ELEVATE to deploy a worker survey in Keraniganj and Narayanganj, two of Bangladesh’s key informal apparel production hubs. A relatively low-tech tool, the survey does not require a respondent to be literate or even own a smartphone. Rather, workers anonymously answer a series of multiple-choice questions by pressing a number on their mobile phone’s keypad using voice response technology. During the weeks after responding to the survey, workers then received a series of informational/educational messages informing them of their rights. In instances where child labor or risk of forced labor was identified, referral operators followed-up to link workers to support services such as skills building activities and/or education. While giving voice to a hidden population, this project not only identified exploitation in informal apparel factories, but supported workers to remove from exploitative conditions.

The Results:

The results of the worker survey revealed high rates of child labor –higher than expected and much higher compared to the formal sector. Poverty, exacerbated by the pandemic, pushed most children into factory jobs. Nearly 9 out of 10 working children reported migrating to the cities for work in the informal sector to be able to support their families’ income. Most of these children live in the nearby slums within walking distance of their workplace. Most had never attended school or were forced to drop out. Children are especially vulnerable to exploitation. Anecdotal evidence shows that employers prefer to engage children because they are more easily convinced to work longer hours for less money. Many children are unaware of their rights and thus less likely to protest when those rights are violated.

Follow-Up:

What to do with these findings? With the Fund’s support, ELEVATE partnered with three local organizations to provide educational and support services to identified victims of child labor. Each of these three organizations- Bangladesh Labour Foundation (BLF), LEEDO, and Community Participation and Development (CPD) – have experience in these two high-risk areas and in implementing educational programs. Each adapted their curriculum and program offerings in response to student needs.

BLF, for example, amended its traditional curriculum to include Bangla language, mathematics, and English, as these were the courses that young workers most requested. CPD, focused on building technical and vocational skills, enabled students to select a program based on their needs and interest. While some preferred to hone skills relevant to the garment industry, others, especially the younger students, were most interested in learning generic trades to improve their future employability and personal self-development. LEEDO, an organization that runs informal schools for street children, primarily targeted children under the age of 14, complementing their curriculum with recreational activities such as Carom Board, Ludo, and gaming.

Of the children who attended these schools, some have left the factory. They have returned to their villages and enrolled in school. Yeasin*, just 9 years old when his father’s injury forced him to quit school and start working, found time to attend one of BLF’s programs in between work shifts. Finding Yeasin eager to exit the factory and continue studying, BLF reached out to his father. Yeasin returned to his family and is now enrolled in the government school in his village.

Other children have moved on to better jobs or better wages. 14-year old Joshin* left school to work in a garment factory after COVID-19 pushed his family into financial crisis. For his labor, he was provided three meals a day, but no wages. After studying English, Bengali, and mathematics as a student in LEEDO’s School under the Sky program- courses that helped him excel in his daily work- Joshin found work in another factory. In his new position, Joshin earns wages that are helping support his family. He expects to earn a promotion soon.

Education is only part of the solution. Reducing vulnerability means changing systems

Educational programs and skills training play an important role in providing children an alternative to working in informal factories, but they are not the solution. Nor is any one program. To ensure children are kept out of factories, we need to address whole systems. This means engaging governments to legislate and enforce labor reform; engaging businesses to change exploitative labor practices; raising awareness to prevent child exploitation; enhancing access to social protection benefits to build financial security; and creating sustainable livelihood options so that mothers, fathers, boys, and girls are not forced into exploitative working conditions.

The Global Fund supports numerous projects to reduce forced and child labor in Bangladesh’s informal factories. In addition to the worker voice survey and the educational programs that resulted, we support research to identify gaps in existing legislation and we recommend specific actions for policy and law enforcement groups, government officials, and brand representatives to take to end forced labor. We invest in the development of innovative tools to help brands, buyers, and suppliers prevent, detect, and remediate forced labor in their operations. The Fair Capacity Platform, for example, helps businesses plan their production capacity better, reducing the probability that they resort to subcontracting or excessive overtime to meet unrealistic order deadlines.

The garment industry is a central pillar of the Bangladesh economy, and so are the millions of men, women, and children who sustain it. The outbreak of a global pandemic showed the world just how vulnerable these workers are, especially those laboring in the informal sector. It also reinforced our commitment to reducing that vulnerability.

If you are interested in partnering with us to end forced and child labor in the apparel sector, please reach out.

*Names in this blog have been changed to protect identities. The legal age of employment in Bangladesh is 14.

Apparel I Bangladesh

Lessons Learned

During follow-up, many children said they couldn’t afford to quit their jobs, or even reduce their workload to participate in the educational programs being offered, despite expressing interest. For some children, engaging in part-time learning could compromise the source of income that their families depend on. Based on findings from the worker voice survey and real-time feedback from children whom the survey engaged, ELEVATE developed the following guidance for governments, donors, civil society, or private sector actors:

- Efforts to provide education or remediation services to working children must assume that children will not or cannot immediately leave their jobs and should accommodate their work schedules (e.g. by offering part-time courses)

- Educational and support services should offer income-replacement stipends or allowances and provision of social safety net services to convince children and their families to enroll in the programs, and eventually transition into the mainstream education system.

- Referral services should target working children as well as their families. Lack of awareness regarding the negative effects of child labor contributes to decisions that put children in factories.

- Programs aimed at reducing child labor should engage other actors such as factory owners, trade union leaders, and the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishment to eliminate child labor.

We create innovative solutions for global brands

Bridging the buyer-supplier gap to root out forced labor in supply chains

Global supply chains are a major perpetrator of modern slavery. With over 16 million victims in the private sector, business involvement is key to sustainable, systems change that eliminates forced labor. In the apparel sector, a lack of transparency between buyers, suppliers, and manufacturers is what often allows modern slavery to go unnoticed.

International apparel brands, particularly those in the ready-made garment (RMG) or “fast fashion” sector, monitor their legally registered Tier 1 suppliers in India. Due to the low pricing and quick turnaround production pressures of the industry, Tier 1 suppliers often sub-contract to unauthorized and unregistered factories that are hidden from brands in order to meet demand. This creates a lack of transparency between buyers (brands) and suppliers, leading to poor monitoring of deeper supply chain operations and allowing forced and child labor to thrive.

To enhance monitoring and make supply chains more visible to buyers, GFEMS and ELEVATE, a business risk and sustainability solutions provider, are creating innovative apparel brand monitoring and remediation systems in India.

ELEVATE has built and tested a predictive analytics tool to detect risks of unauthorized sub-contracting and forced labor practices. The tool uses institutional knowledge, third-party data supply chain data, and new procurement audit data to identify which Tier 1 suppliers are at high risk of using unauthorized contracting to meet their production orders. Along with identifying high-risk suppliers, ELEVATE has also developed remediation processes for brands, Tier 1 suppliers, and informal/unauthorized factories to collaborate to improve labor practices, ensuring that factories are incentivized to participate and remain transparent.

Despite a slowdown in the apparel industry during the COVID-19 pandemic, ELEVATE has already generated significant brand interest in hosting social compliance audits. To date, the project has:

- Established partnerships with four key global brands

- Completed 22 on-site assessments

- Generated 13 supplier reports on risk of unauthorized sub-contracting.

Five monitored suppliers have indicated varying levels of extreme to medium risk of unauthorized sub-contracting. Two of those suppliers have agreed to deliver a remediation plan, including onsite capacity building with suppliers.

By offering both modern slavery risk identification and effective remediation plans for suppliers who are at risk, the tools developed in this project both allows buyers to make smarter decisions about their suppliers, and provides suppliers with plans to improve their practices and continue operating. Both are essential for generating and maintaining systems level change that eliminates forced labor from supply chains.

This project was funded through a grant made by the U.K Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). Any opinions in this article do not reflect the opinions of FCDO.

GFEMS and SAI launch new partnership, targeting modern slavery in India’s apparel sector

GFEMS and SAI launch new partnership, targeting modern slavery in India’s apparel sector

GFEMS is working with Social Accountability International (SAI), with funding from the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) to disrupt the prevalence of modern slavery in the ready-made garment (RMG) sector in India. As part of the Fund’s Apparel and Manufacturing portfolio, SAI will develop a digital platform to incentivize and support improvements in labor compliance by preferentially linking ethical suppliers with buyers. Ultimately, SAI’s platform will reduce unauthorized subcontracting, a key driver of forced labor.

There are an estimated 12 million workers employed in India’s RMG sector, though that number is likely to be higher due to the uncounted home workers and employees of illegal or unauthorized subcontracting facilities. Factories in India’s RMG sector are known to drive multiple indicators of modern slavery, including mandatory overtime work, unsafe working conditions, and unauthorized subcontracting. These conditions are brought on, in part, by poor understanding of the connection between strong labor practices and the opportunity for factories to be reliable and efficient suppliers.

While these problems are well known, there are few opportunities for buyers to gain full transparency into their supply chains and for suppliers to improve their production planning. Both factors would incentivize and enable better social compliance.

SAI’s project will fill these gaps by developing a digital platform to combine suppliers and buyers and a suite of tools to help both parties improve their labor practices. Aligning with the Fund’s intervention framework, this project addresses the demand for cheap goods and services and aims to transform the corporate environmental norms that allow slavery to persist in the sector.

Leveraging SAI’s existing work in Bangladesh, the project will develop tools and training to improve buyers’ purchasing practices and suppliers’ capacity and production planning. Helping buyers manage their purchasing orders and suppliers plan their production schedules will reduce the risk that suppliers will take on the unrealistic targets that result in unauthorized subcontracting. Unauthorized factories sit outside government regulation and most social audits and therefore present a much higher risk for forced labor violations. SAI’s tool will expand on existing data sets by quantifying the effects of purchasing practices on supplier production capacity—e.g. the effects of unpredictable volumes, last-minute order changes, design changes, long payment periods, etc. This will help buyers and suppliers to better predict supplier capacity and reduce the likelihood of subcontracting.

The project also represents a deepening commitment to the Fund’s work on supply chain management and risk mitigation efforts. GFEMS has also created an award winning Automated Forced Labor Risk Detection tool, which helps buyers to detect risk of forced labor in their supply chain with 84% accuracy. Additionally, GFEMS is funding ELEVATE to develop a predictive model to help brands identify risk of unauthorized subcontracting in their supply chains and take remediation steps.

GFEMS looks forward to sharing learnings from SAI’s work with stakeholders in India’s RMG sector. Learn more about the FCDO partnership, the Fund’s portfolio, and scoping research.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn for updates on the latest developments, news, and opportunities with GFEMS.

Focused on sustainability, GFEMS launches seven new projects in India and Bangladesh

Focused on sustainability, GFEMS launches seven new projects in India and Bangladesh

GFEMS is proud to share the launch of a new portfolio of interventions and innovations with our partner, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). The portfolio is expected to total approximately 9M USD.

The FCDO portfolio represents deepening investments in India and Bangladesh, following the inaugural GFEMS portfolio launch in late 2018, and two additional launches with Norad and the US State Dept. Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons earlier this year.

Originally scheduled to launch in spring 2020, all of the projects in this portfolio have been adapted to reflect and respond to new needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Working with our partners on the ground, these projects are now better designed to mitigate exacerbated vulnerability, adjust to remote environments, and contribute to responsible recovery.

“The FCDO portfolio reflects thoughtful, nuanced, and deliberate action to disrupt modern slavery.”

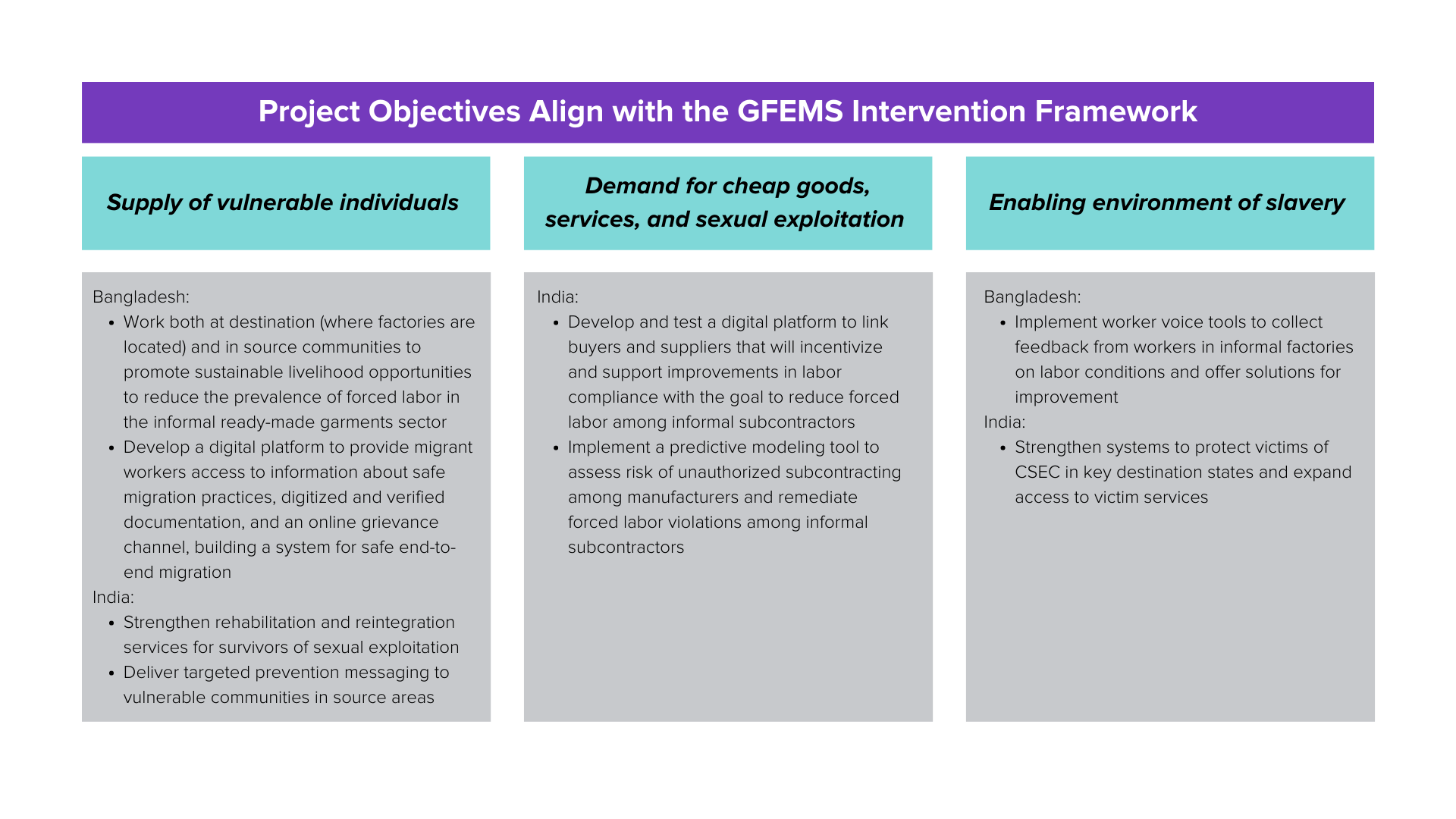

Prior to project launch, GFEMS engaged in extensive scoping and design phases to identify the geographies and sectors with the highest potential for impact. The portfolio, designed based on the findings from that efforts, addresses the following opportunities:

- Overseas Labor Recruitment in Bangladesh

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation (CSE) in India

- Forced Labor in the Apparel Sectors in India and Bangladesh.

GFEMS is funding a total of seven projects across these opportunities:

- IJM– Strengthening Systems to Protect CSEC Victims and Sustain Freedom in Maharashtra

- Seefar– Empowering Children, Families and Communities to End Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children

- BRAC– Reducing Forced labor in Informal Ready-made garment factories in Bangladesh with Sustainable Livelihood Opportunities

- SAI– Improving Buyer-Supplier Engagement, Purchasing Practices, and Capacity/Production Planning India’s Informal Ready-Made Garment Supply Chains

- ELEVATE– Safestep: A Responsible Recruitment Platform for Safe Migration in Bangladesh

- ELEVATE- Laborlink: Disrupting the Prevalence of Forced/Bonded Labor in Bangladesh Informal Ready-Made Garments

- ELEVATE- Developing Predictive Analytics Tools to Disrupt Forced and Bonded Labor in India’s Informal Ready-Made Garments

Projects within the portfolio address the key pillars of the Fund’s intervention framework– supply, demand, and enabling environment of modern slavery. They address core challenges that prevent sustainable reduction in prevalence.

Sustainability is a key theme across the projects, and across the Fund’s wider investment portfolio. GFEMS designs programs and strategies for future investments with sustainability in mind. Funding focuses on both projects with high potential for replication and scale, and those that leverage both national priorities and market demands. All projects are informed by, and tailored to, the populations GFEMS seeks to serve. Within the FCDO partnership, GFEMS specifically targets sustainable changes in supply chain practices, project sustainability through increased government and private sector engagement, and sustainable livelihoods for survivors.

“The FCDO portfolio reflects thoughtful, nuanced, and deliberate action to disrupt modern slavery. The Fund worked closely with partners to develop holistic programming that is based on the best available evidence, but also flexible enough to respond to evolving needs in the field. We are excited to launch these programs with our incredible partners and grateful for the support of FCDO,” said GFEMS Director of Grant Programs, Helen Taylor.

GFEMS will share more information about the portfolio, projects, and our implementing partners in the following weeks. We look forward to sharing the impact, successes, and lessons learned from this portfolio.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn for updates on the latest developments, news, and opportunities with GFEMS.