Financial exclusion is a primary driver of vulnerability and exploitation.

Could financial inclusion be the key to reducing vulnerability to modern slavery?

This post is co-authored by Laura Gauer Bermudez – Director of Evidence & Learning, GFEMS; Shukri Hussein – Country Manager East Africa, GFEMS; Timea Nagy – Founder of Timea’s Cause; Bart Robertson – MEL Manager, GFEMS; and Leona Vaughn – Vulnerable Populations Lead, UNU FAST Initiative.

Released from the grip of a trafficker, you return to your home community.

You lack a documented employment history, your identification documents have been stolen by your trafficker, and you may not yet have a permanent address. Each of these circumstances is precluding you from opening a bank account. Without steady financial footing, you are prone to be exploited again, entering a cycle of lost freedoms and being denied access to the very structures that can help you reclaim your agency and independence.

This is a story of frustration, oppression, and injustice. And it is a story that is lived time and time again by survivors of modern slavery and human trafficking. It is also the basis of what places individuals and communities at risk of exploitation.

Approximately, 1.7 billion individuals – 31% of the world’s adult population is ‘unbanked’, meaning they lack access to formal financial institutions such as banks and lenders. Addressing this issue has been part of broader development and poverty reduction strategies globally for over a decade. Yet, the connection between financial inclusion and reducing vulnerability to modern slavery is a relatively new conversation, one that the Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) and the Finance Against Slavery & Trafficking (FAST) Initiative have identified as critical and are actively mobilizing resources to address.

What is financial inclusion?

Financial inclusion means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs – transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance – delivered in a responsible and sustainable way.

Financial products and services can include bank accounts and savings products as well as loans and insurance. Inclusive digital financial services, spurred by a rise in financial technology (FinTech), is helping to grow access to services such as mobile money which allow banking transactions from the convenience of a personal cell phone.

However, barriers to access remain common. The high cost of opening accounts, expensive transaction fees, complex application processes, and lack of access to digital services, leave many out of the formal financial system. Lack of financial literacy and gender norms that discourage women’s independent access to financial services create additional barriers to service.

These barriers limit the ability of individuals to safely save, invest, or access affordable lines of credit, all with significant consequences. Not only is an individual left with little to no power over their own financial resources, but their exclusion from the system perpetuates further marginalization, as lack of engagement places individuals in ‘high-risk’ categories. Given that a significant level of those who are unbanked also represent those facing social exclusion – based on age, citizenship, race, gender, disability, and socio-economic status – financial and social exclusion become reinforcing.

Here are some ways financial exclusion specifically increases vulnerability to modern slavery and what kinds of products, services, and access to financial institutions can make a tangible difference in reducing that vulnerability:

Financial exclusion limits ability to withstand economic shocks, necessitating risky labor and migration practices

Poverty is, by far, the most ubiquitous and obvious factor driving susceptibility to modern slavery. However, it is the inability to weather economic shocks that is a defining feature. The illness or death of a primary income earner. Financing large but socially required events such as weddings or funerals. Protracted conflict or political instability. Income or job loss due to macro-economic downturns. For those living on the margins, such shocks leave few options. The current economic downturn resulting from the pandemic is a prime example. The devastating effects of climate change are another shock, increasingly witnessed in vulnerable communities reliant on agriculture for their livelihoods.

The economically insecure have very few options to cope with and protect their families from these hardships. Those who are unbanked and with limited access to affordable credit or micro-insurance are often forced to cover these expenses by taking out sizable loans from informal money lenders at usury rates. Alternatively, others resort to irregular or risky migration as a means to meet these financial needs, which can lead to exploitative situations. Some may also receive advance payments or loans from employers, which can facilitate a bonded labor relationship.

Including survivors in the design of products and services is one of the first steps we can take to be more inclusive.

In order to most effectively serve groups at risk of slavery as well as survivors, designers of financial products should consult individuals and groups with this lived experience to understand their needs. For instance, GFEMS invested in SafeStep, an online platform for migrant workers from Bangladesh relocating to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries for employment.

Learn MoreFinancial exclusion hinders reintegration of survivors

For survivors of human trafficking and modern slavery, financial exclusion represents a continuation of their trauma. Official identification documents such as passports are often stolen by their assailants, and in some cases their identities are used to defraud or amass debt. This can present a barrier to their financial recovery when they have escaped from these situations, as they struggle to open basic banking accounts for wages and even to access legal compensation they may have been awarded. Financial exclusion, a lack of access to financial services and knowledge, is not only a form of re-victimisation, but has consequential negative impacts on survivors’ financial reintegration, advancement to financial independence, and well-being and damages future opportunities for housing, mortgage, credit and employment. This leaves survivors vulnerable to repeat exploitation and abuse.

Financial exclusion perpetuates systemic risk of exploitation

Modern slavery is not only a result of individual vulnerability, but also systemic issues within industry. Market risk and volatility can be pushed down the supply chain to actors who are least prepared to cope. Such is the case in the construction sector in India, representing over 60 million jobs. The sector is highly dependent on low-paid, migrant labor and a system of sub-contracting construction orders to micro-contractors (MC). MCs are the primary employers of these migrant workers. They often operate informally, have limited access to affordable credit, and have to manage day-to-day business operations in a highly volatile market. Delayed payments are common and work orders inconsistent. These and other challenges can limit MC’s ability and willingness to treat their workers ethically. Worker exploitation and withheld wages are the norm.

Financial exclusion limits access to social protection schemes

The unbanked may be limited in their ability to access social protection schemes. Initial evidence has shown that people without bank accounts or access to mobile money were most likely to be excluded or receive far less monetary support from governments than those with digital financial access during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This has a specific impact on rural populations, indigenous communities, young people, and women. These groups, primarily who were in informal work and also more likely to borrow from informal lenders, were placed at higher risk of abuse and exploitation.

Expanding Financial Inclusion – What’s Next?

If financial exclusion can be characterized as a lack of power and control over one’s economic resources, financial inclusion can be associated with greater financial power, control, independence, and agency, all of which are necessary to be fully free from exploitation.

So what are the products, services, and opportunities for access necessary to spur a meaningful reduction in modern slavery vulnerability? Here are our recommendations:

Prioritise financial inclusion as a form of protection against slavery and trafficking

Recognizing the role that financial inclusion plays in reducing modern slavery vulnerability, and explicitly considering this in the wider financial inclusion field, is a key next step for governments, civil society, and the private sector. Institutional funders and philanthropists can play a role in mandating financial inclusion activities within their portfolios to address slavery and trafficking. Governments can integrate financial inclusion activities into their policy strategies for vulnerability reduction and the private sector can consider innovative ways to improve access to financial products and services to workers along their supply chain. Financial services providers should be educated on modern slavery, specifically debt bondage, to understand how their products can best reduce this power dynamic for workers across the globe.

Exponentially expand public-private partnerships to address financial exclusion

NGOs and CSOs working to address slavery and trafficking should intentionally enhance collaboration with financial service providers, mobile money operators, and government agencies that offer safety net programs to design effective and sustainable interventions that increase financial inclusion. Similarly, private sector actors should seek opportunities to pair with NGOs and CSOs to reach and serve populations that have been left out of the formal financial system.

Establish more community-based savings and loans groups as an on-ramp to formal financial institutions

Governments and NGOs can facilitate group savings and loan initiatives such as village savings and loan associations (VSLA) and self-reliance groups (SRG). These initiatives provide access to credit as well as financial literacy training. Group savings initiatives can be effective platforms for delivering important skills training, increasing the social capital and resilience of group members and further reducing vulnerability to modern slavery. For this reason, group savings initiatives are often a part of an integrated suite of services in economic development programming, as evidenced in the Ultra-Poor Graduation approach and many others. While these initiatives tend to sit outside the formal banking system, they exist as part of a continuum of financial services ranging from the informal to formal and can serve as an onramp to formal financial services.

Provide guidance to Financial institutions on how to manage risks to vulnerable populations and ensure financial inclusion, while complying with relevant AML/CFT laws

There is a need to raise awareness in financial institutions about how these issues interact, in a way that also gives reassurance that anti-money laundering/counter terrorist financing laws and regulations are not compromised. Guidance could include ensuring considerations of risks to vulnerable populations, in relation to financial exclusion and heightened exposure to the risk of slavery and trafficking, are within banking risk assessment and management processes. Guidance could also address ‘derisking’ practices, including how and when they are an appropriate response to human rights concerns and also can unintentionally exacerbate risks to vulnerable people.

Integrate financial inclusion and financial literacy initiatives within any economic empowerment portfolio

Financial literacy is an important element in achieving financial inclusion. Yet many economic empowerment programs, particularly in the anti-slavery/anti-trafficking space, fail to include a comprehensive financial literacy training package, either due to funding shortages or limited capacity. This lack of emphasis on financial literacy leaves participants with an inability to save, invest, and protect themselves against economic shocks after the project has ended.

Expand digital financial services and digital financial literacy campaigns

Mobile finance platforms such as MPESA, used by 31.2 million Kenyans, enables users to open a bank account without onerous form filling and provides users with access to a savings account and loan opportunities. This ease of access creates a convenient option for at-risk groups as well as survivors who may lack the necessary papers required to open an account. Mobile finance has been a game-changer for financial inclusion in Kenya and is seen as a model for the rest of the world. Significant expansion of mobile money offerings alongside digital financial literacy has the potential to exponentially increase access and participation in the financial system for individuals and groups whose prior exclusion created notable vulnerabilities and barriers to their own financial independence.

Incentivize ethical business practices through the provision of financial services

Mapping the employment structure of an industry prone to modern slavery can uncover stressors that may be making it difficult for employers to abide by ethical business practices. GFEMS is currently partnering with several organizations to provide micro-contractors in the construction industry in India with business training and conditional loans. Loan provision is contingent on the implementation of a minimum set of ethical business practices by the recipient. An impact evaluation of this project is currently underway, and we anticipate that the loans will help micro-contractors to better manage cash flow and work orders, enabling them to more feasibly adopt ethical business practices.

Invest in savings accounts for survivors and populations at high-risk of slavery and trafficking

Individual Development Accounts (IDAs) have long been touted as a vehicle for increasing assets and hope for the future among low-wealth populations. Matched savings for low-income populations establishes a mechanism for accumulating savings and assets, an opportunity that would otherwise only be available to middle to high-income earners with matched savings through their employers. Governments, charities, and private sector entities should consider establishing IDA accounts for select groups in order to offer the same opportunities for wealth accumulation afforded to less marginalized populations.

Include survivors in the design of products and services

In order to most effectively serve groups at risk of slavery as well as survivors, designers of financial products should consult individuals and groups with this lived experience to understand their needs. For instance, GFEMS invested in SafeStep, an online platform for migrant workers from Bangladesh relocating to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries for employment. Extensive consultations were held with workers to understand what was most effective to meet their needs, resulting in a comprehensive budget calculator, helping migrants understand the ‘true’ cost of migration. Consulting affected populations on their needs will ensure greater uptake and impact.

Join Us

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery is a multi-donor fund launched in 2017 to catalyze a coherent global strategy to end forced labor and human trafficking. GFEMS programs around the world are working at the intersection of financial inclusion and modern slavery, bringing together leaders and innovators from both fields to drive impact. Activities include developing, piloting, and scaling innovative new financial products — be they to economically empower survivors of trafficking, to reduce financial fragility among migrant workers, or to alter employer behavior in the informal apparel and construction industries — and conducting and disseminating studies to increase understanding of the individual-level financial drivers of modern slavery risk.

Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking Initiative, based in the United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, is working to mobilise the financial sector against slavery and trafficking. Part of this work is called the Survivor Inclusion Initiative which in its first phase has assisted survivor support organisations and participating banks in the US, Canada and UK with the opening of over 2,000 survivor bank accounts. This programme operates from the position of addressing survivor needs. It works closely with survivor support organisations to be able to support survivors in navigating the process, this includes being able to ratify survivor identity. It works to empower survivors with choices, in terms of banks and account types e.g. online banking for those not comfortable with face-to-face account opening. It supports banks to address and overcome documented challenges such as ‘de-risking’ and perceived conflicts with anti-money laundering or counter terrorism financing rules.

We’re making a difference in the lives of tens of thousands of migrants and their families. Join us today.

Get InvolvedFinancial Security Means Safer Migration: Reducing Vulnerabilities Among Migrant Workers in India’s Construction Industry

In December 2020, an operator for the Jan Sahas helpline answered a call from a man claiming that his brother and six other workers were being held in inhumane conditions and against their will at a construction site in Faribadad. The man reported what his brother had told him- that since arriving, the migrants had received no pay for their work.

The Jan Sahas team responded immediately. They reached out to the local police and District Collector (DC) of Faridabad and an investigation was launched. Quickly after arriving at the site, the inspector was able to confirm the veracity of the claim: the workers had indeed been denied wages; none had even enough money to leave the site. An application to the DC filed on behalf of the migrants resulted in an order for restitution against the employers. They were forced to pay Rs. 1,16,340 (about $1,600 USD) in back wages to the workers they had defrauded and another Rs. 9000 (about $125 USD) to cover their transportation home. The network that Jan Sahas, together with GFEMS, set up to monitor and respond to cases of forced labor had worked. The man who had made that initial call to the helpline was reunited with his brother and the other migrants recovered what they had earned.

The network that Jan Sahas, together with GFEMS, set up to monitor and respond to cases of forced labor had worked. The man who had made that initial call to the helpline was reunited with his brother and the other migrants recovered what they had earned.

The helpline is an essential component of Jan Sahas’ strategy to reduce forced labor in India’s construction industry, but it is only one part of more comprehensive programming. While providing support to those encountering situations of forced labor, Jan Sahas is committed to changing the systems that create vulnerabilities in the first place. In partnership with GFEMS, Jan Sahas developed programming to assess risk factors for forced labor among India’s migrant workers to better mitigate those risks; to raise awareness and ensure access to government entitlements to help migrants build a stronger safety net; and, in partnership with Pratham and Sambhav Foundation, to train employers on ethical labor practices to create safer and better work experiences. These collective efforts have made a difference in the lives of tens of thousands of migrants and their families. Many thousands more are less likely to experience forced labor or exploitation because of the efforts of Jan Sahas and our partners on the ground.

India’s construction sector

Nearly 40% of India’s population or 450 million people are internal migrants. (This reality was made clear to the world last year when news outlets broadcast the mass exodus that followed the state-issued lockdown.) India’s construction industry is the country’s second largest employer and attracts a large number of migrant workers each year. Approximately thirty to fifty million of India’s construction workers are internal migrants.

While construction work offers an opportunity to earn additional income, especially during the agricultural off-season, evidence indicates that 10 percent or more of migrant construction workers – potentially five million people- could be in forced labor. Various factors are contributing to this high rate.

Despite an unprecedented contraction of India’s construction industry in the first half of 2020 in response to COVID-19, the sector has made a strong recovery (despite another recent outbreak), and remains one of the fastest growing construction markets in the world. This, combined with a severe shortage of skilled labor and an abundance of informal recruitment brokers and middlemen eager to fill this labor gap, has significantly enhanced migrant workers’ vulnerability to exploitation.

Jan Sahas: Promoting safe migration and worker protection

Jan Sahas targeted the 450 kilometer migration corridor stretching from Bundelkhand to Delhi. Of the estimated two million migrants who travel this route annually, early prevalence estimations show a rate of forced labor between 7.5 and 10%.

Building a safety net to reduce forced labor risks

For many migrant workers who live in a perpetual state of transit, it is difficult to access government entitlements. Though many are simply unaware of what benefits they are entitled to, others lack the formal documents needed to access these benefits. To overcome both of these challenges, Jan Sahas implemented programming to raise awareness of social welfare entitlements among migrant workers and to help migrants navigate complex government structures and processes.

Before pursuing entitlements, Jan Sahas organized a series of awareness-raising community meetings to educate workers on existing benefit schemes and criteria for enrollment. Despite early skepticism from workers who had participated in surveys before but never received promised benefits, the Jan Sahas team worked to gain worker trust and helped thousands register for entitlements including food rations, pensions, and those offered specifically to construction workers under India’s Building and Other Construction Workers (BOCW).

Registering for entitlements can be cumbersome. In some localities, workers must present in-person at labor department offices to access benefits, which often means taking off work. BOCW cards require proof of work in the same location for 90 days, a requirement that many migrant workers are unable to meet. Others simply do not have the formal documentation needed for a successful application.

To help overcome some of these obstacles, Jan Sahas guided migrant workers through the application process, clarifying more technical language and assisting in the preparation or collection of required documents. During the project period, Jan Sahas helped over 27,000 workers and their families access direct cash or cash-equivalent benefits. While follow-up interviews with workers revealed that most would not have known about entitlements or how to access them without Jan Sahas’ intervention, these entitlements provide a safety net for workers, allowing them greater agency to choose when and where they will work.

Jan Sahas helped over 27,000 workers and their families access direct cash or cash-equivalent benefits. Follow-up interviews with migrant workers revealed that most would not have known about entitlements or how to access them without Jan Sahas’ intervention.

Beyond entitlements, awareness-raising campaigns introduced migrant workers to Jan Sahas’ toll-free helpline. The helpline is an outlet for workers to file grievances, report instances of forced labor or inhumane treatment, seek redress for lost wages, and access legal support services. In an expression of gratitude for the establishment of a helpline, a worker in Delhi reported that he “lost between INR 10,000-15,000 ($134-200 USD) of wage payments before a helpline was operational.”

Supporting Migrant Workers during COVID-19

When COVID-19 struck in spring 2020 and India entered lockdown, the response from Jan Sahas and other implementing partners was immediate. As the true impact of the pandemic began to show in job losses and rising unemployment, the Indian government increased entitlement allotments and issued new benefits to help mitigate the worst effects. Jan Sahas, with a tracking and communication system already in place, intensified its outreach efforts to ensure migrant workers, a group left even more vulnerable by the pandemic and subsequent shutdowns, could access needed support. A migrant from Faridabad whom Jan Sahas had helped register for government entitlements captured the dire reality for many migrant workers during COVID: “Without ration or cash transfers, we would not have survived the challenges of COVID-19.”

In addition, Jan Sahas was able to utilize the existing programmatic framework to identify and provide food relief to over 1,000 of the most vulnerable migrant households.

Gathering data to assess risk factors and improve programming

Foundational to Jan Sahas’ programming was the development and implementation of a longitudinal migration tracking (LMT) system. This system is designed to capture data on migrant workers to better understand risk factors for forced labor, paying particular attention to whether program interventions decreased the likelihood of exploitation.

To build a strong evidence base, Jan Sahas conducted extensive outreach at various departure points, including home villages and transit hubs, to register workers. Successfully registering over 89,000 migrant workers, surveyors then followed up at destination sites to assess the effectiveness of program interventions- specifically, access to entitlements and operation of a helpline- on reducing the incidence of forced labor. Follow-up communication with registered workers, combined with worker interviews, revealed that Jan Sahas’ programming was making a difference. Workers who were helped to access social protection benefits reported additional income and savings while those accessing the helpline were able to recover unpaid wages, escape forced labor conditions, and generally, feel safer. Jan Sahas hopes this data will encourage greater investment in similar prevention efforts. When more is known about migrant workers and experiences and what factors increase risks of exploitation, targeted action can be taken to reduce and ultimately eradicate forced labor.

Engaging employers to reduce the risk of forced labor

While Jan Sahas supported migrants to build greater financial security and provided them an outlet to air grievances and pursue justice, other implementing partners focused on developing the capacity of micro-contractors. Micro-contractors are the primary employers of unskilled and semi-skilled construction workers, employing between 5 and 25 persons at a time. Pratham and Sambhav led an effort to train micro-contractors on ethical labor practices to reduce the risk of forced labor among vulnerable migrants. Workers employed by trained micro-contractors expressed a desire to stay on with these employers as they had taken steps to create safe and equitable work environments, including ensuring on-time wage payments, providing safety equipment for risky jobs, and helping meet essential needs such as food and accommodation at destination sites. Women working for trained micro-contractors noted especially the attention these employers paid to eliminating discriminatory gender practices in the workplace. Unlike other employers, program-trained micro-contractors paid women separately from their spouses, ensuring greater female economic agency.

Building local capacity to effect sustainable change

Jan Sahas’ programming to address forced labor in India’s construction industry has reached tens of thousands of workers. Some have received support to exit forced labor conditions, others have registered successfully for entitlements to reduce risks of exploitation, and still others have filed grievances to recoup lost wages. Though this program may have formally concluded, Jan Sahas set up people and systems to carry its benefits forward. They successfully trained hundreds of social advocates or “barefoot lawyers” who will continue to share information on labor laws, rights, and entitlements with migrant workers and aid in benefit enrollments. Moreover, Jan Sahas continues to collaborate with key government actors at each stage of program implementation, including India’s Department of Labor, and other stakeholder groups across civil society, philanthropy, and the private sector to sustainably end forced labor. We are proud to be a part of this collaboration.

Jan Sahas is a community and survivor-centric nonprofit organization committed to ending sexual violence and forced labor. To learn more, please visit Jan Sahas.

This article and the project it references were funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of State.

Employing innovative new funding mechanisms can mobilize additional capital, money which is badly needed if we are to end modern slavery for good.

Get InvolvedMoving the Needle: How Anti-Slavery Efforts Can Use Innovative Finance to Mobilize Funding and Make Change

Innovative finance has been put to work for several years across international development. However, anti-slavery efforts still tend to rely on traditional grant finance from donors, whether governments, multilateral institutions, or philanthropic ventures. New funding approaches could help bring much-needed additional finance into preventing trafficking.

Among other ideas, GFEMS is interested in outcomes-based approaches like Development Impact Bonds, which aim to use donor finance as efficiently as possible. Instead of tying traditional grant finance to inputs or activities, which may not always link to long-term change, money is tied to the achievement of tangible, long-term outcomes for beneficiaries. And instead of spending time on donor reporting, NGOs can concentrate on solving problems.

Why innovative finance?

Across the global social sector, innovative finance approaches have become relatively mainstream over the past few years. The international development community has recognized that the gap between the donor finance available and the funding needed to achieve the UN’s SDGs is enormous: between $1.4T and $3T per year. This suggests that private finance, including the global capital markets, needs to be harnessed in order to close this gulf, and that existing donor funds must be used more efficiently. For instance, impact investing, which focuses on achieving social or environmental impact as well as financial return, has become a common method of boosting revenue-generating and socially impactful sectors like financial inclusion, health, and energy; green bonds have raised investment for environmental projects; and conditional cash transfers have been used widely to support children’s education and keep them out of work.

However, we still see few of these initiatives in anti-slavery work. Funding in our space remains oriented towards traditional grant finance.While donors have worked hard to achieve impact, anti-slavery and anti-trafficking work is a relatively young part of the global agenda on social issues and human rights, and remains deeply underfunded. Today, even the most generous estimates put the total amount of funding for combatting modern slavery at approximately $700M annually, versus an annual operating budget of almost $10B for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, a sector serving a very similar number of beneficiaries.

Employing innovative new funding mechanisms can mobilize additional capital, money which is badly needed if we are to move the needle towards ending modern slavery for good.

How can innovative finance mobilize resources to propel anti-slavery efforts? There are two primary ways that innovative finance can make a difference:

- Innovative finance can be used to bring new forms of private capital into the anti-slavery space. For instance, blending grant finance with private investment, or providing guarantees, can reduce risk for private investors and allow capital to flow into frontier markets or otherwise risky industries. Equally, supporting private firms with grants for research and development (R&D) can help them to become investment-ready. An example might involve the offer of a guarantee or an R&D fund to incentivize private investment in a financially risky new social enterprise which works to end modern slavery, like a responsible recruiter or a worker voice technology tool.

- Innovative finance can also be used to make more efficient use of existing grant funding. Proving value for money and enhancing impact is a crucial way of incentivizing donors to invest in a particular project or sector. Approaches which seek to maximize efficiency include conditional cash transfers, challenge funds, and outcomes-based finance, among others. Over the past year, GFEMS has been exploring the relevance of outcomes-based finance for modern slavery.

Case Study: Outcomes Based Finance

Traditional grant finance, which is common in anti-slavery work, may not always be the most effective or efficient way to achieve long-term, systemic change for our beneficiaries: survivors of modern slavery. Traditional grant finance has historically tended to focus on defining program inputs; measuring success in outputs that are easy to count; and closely managing grants. However, this approach fails to align funding with long-term outcomes for beneficiaries. For instance:

- In the water and sanitation sector, donors may find it preferable to focus on developing infrastructure, such as water pumps and latrines, rather than measuring whether or not beneficiaries have the safe, sustainable water sources that they need. To have sustainable water sources, beneficiaries need regular operations and maintenance of their water points. This, however, may be harder to plan for and measure than how many latrines or water pumps are installed.

- In education, it is common to measure success through assessing rates of school attendance or elements of the classroom environment. However, this may not reflect whether students are learning or the quality of education. To provide the best educational environment, students need good teachers, the right learning materials, and attention paid to unique needs- a complex and difficult-to-measure set of factors.In modern slavery, it is often simplest to measure the number of participants or people engaged in a particular program, such as a reintegration program providing skills training, or a behavior change communication program to educate people about risky migration. However, program participation does not guarantee results. What we need to measure is whether skills-training participants can support themselves in reintegration, or whether behavior change communication results in reduced risk of modern slavery.

- In modern slavery, it is often simplest to measure the number of participants or people engaged in a particular program, such as a reintegration program providing skills training, or a behavior change communication program to educate people about risky migration. However, program participation does not guarantee results. What we need to measure is whether skills-training participants can support themselves in reintegration, or whether behavior change communication results in reduced risk of modern slavery.

Much of the traditional grant finance approach has been driven by an understandable aversion to risk when spending public money. However, traditional grant finance isn’t risk-free: prioritizing inputs over outcomes is unlikely to ensure value for money in public spending. It can create heavy administrative burdens for grantees and typically doesn’t incentivize innovation in service delivery. Traditional grant finance tends to reward NGOs which are best able to meet reporting requirements, rather than those with the strongest track record or best potential to achieve outcomes.

Outcomes-based finance, on the other hand, involves donors paying for long-term outcomes, rather than inputs or outputs. When donors can find a way to prioritize long term outcomes, they can make sure their money is being spent on exactly what’s intended: the achievement of long-term impact in the lives of beneficiaries.

When donors can find a way to prioritize long term outcomes, they can make sure their money is being spent on exactly what’s intended: the achievement of long-term impact in the lives of beneficiaries.

Importantly, funding in this way allows service providers to focus solely on achieving outcomes, rather than sticking to the inputs and activities which are specified in a donor’s logframe. They can be flexible, adaptive, and data-informed in their implementation. Instead of spending time on donor reporting, they can concentrate on solving problems.

Two questions naturally arise from this idea: first, how does the donor know if outcomes have been achieved or not? Donors typically employ independent third-party evaluators, who are used to running Randomized Control Trials and similar evaluation exercises which rely on objectivity and accuracy. In the examples above, this might involve measuring the educational attainments of a group of children, perhaps through testing readiness for the next grade; or running surveys to analyse whether families have been able to access the amount of safe water that they need. Donors then only pay out if the evaluator assures them that the program has been successful.

Second, who funds the program up front? Is the service provider expected to fund it themselves, and take the risk that they won’t be successful? This may be possible, depending on the size and financial security of the service provider. But in most cases, a social investor – an organization with a joint social and financial mandate- gets involved to provide working capital to the program. If the program is successful, the investor is repaid by the donor, plus a below-market return. One of the first and most successful examples of this approach in international development was used to fund the Educate Girls Development Impact Bond in India, which sought to keep girls in school and improve their learning. The investor in this case, UBS Optimus Foundation, received an internal rate of return of 15%, to compensate them for the risk they took in funding the project up-front.

Among other innovative finance approaches, GFEMS is interested in piloting outcomes-based finance in the modern slavery space for the first time. We believe it may be particularly effective to explore skilling models for survivors, since long-term outcomes in skilling are relatively straightforward to measure: these could include job starts, sustainment, progression, or satisfaction, and could be paired with measurement of mental health outcomes to ensure a holistic consideration of reintegration. We are also interested in trialing outcomes-based finance to prevent child labor or child marriage, given the success of outcomes-based finance programs in education, as seen in India’s Educate Girls.

We are looking to test and understand whether this innovative new funding model really can help grant finance work harder: can it better serve program beneficiaries and move us closer to ending modern slavery? We think it can.

If you are interested in learning more or contributing to our thinking, please contact olivia@gfems.org.

Micro-contractors can help end forced labor when they are incentivized to adopt ethical business practices.

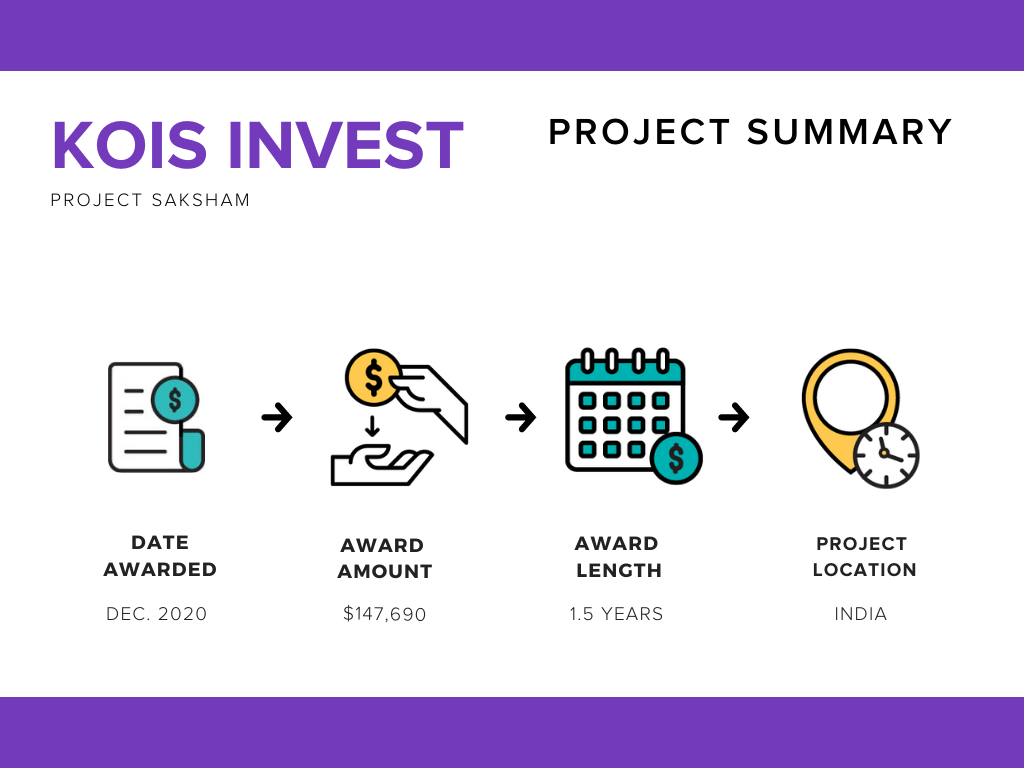

Kois Invest

Kois is part of a consortium of GFEMS partners working to sustainably reduce prevalence in India’s construction sector. This project incorporates learnings from previous GFEMS efforts to incentivize micro-contractors, independent contractors who employ 5-20 workers apiece, to adopt ethical behaviors, eliminating exploitation in the construction supply chain.

About Kois

Kois is an impact finance firm that creates innovative finance mechanisms and uses impact investing & fund management to scale financing solutions. Since its first investment in 2010, Kois has aimed to create a better world for underserved communities. Through innovative finance and impact investing, Kois turns projects with high societal & environmental impact into tangible investment propositions for public & private sector clients.

Driving Financial Sector Innovation in the Global Strategy to End Modern Slavery

Driving Financial Sector Innovation in the Global Strategy to End Modern Slavery

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) is pleased to share the expansion of our Global Finance portfolio to include an initiative focused on use of new payment technologies and virtual currencies by traffickers.

This initiative will evaluate new payment technologies and virtual currencies tied to online sexual exploitation of children (OSEC), determine how to identify these transactions, and develop forensic techniques for investigating the illicit financial flows to traffickers. Building on the Fund’s recent work with partners in the Philippines and the UK to identify and disrupt financial flows tied to online sexual exploitation of children (OSEC), these initiatives are designed to drive development of solutions with potential to be replicated globally.

Mobilizing the financial sector is a critical component in the Fund’s comprehensive strategy. The financial sector has tremendous potential to drive systemic change and play a key role in making modern slavery economically unprofitable.

Beginning in 2018, when GFEMS CEO Dr. Jean Baderschneider served as a commissioner on the Liechtenstein Financial Sector Commission on Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking and building off the efforts of the ensuing FAST Initiative, GFEMS has accelerated its investment in financial sector innovation and partnerships. To-date, GFEMS has committed over 1 million USD in funding to its Global Finance initiatives.

This Global Finance portfolio is strategically designed to leverage and integrate diverse funding streams, driving innovation and more effectively mobilizing the financial sector.

One component of the Fund’s financial sector strategy is leveraging the power of responsible investors to drive meaningful, sustainable actions by companies to address forced labor risks in supply chains. For companies to take meaningful action, they first need actionable insights on forced labor risks in their supply chains. However, existing forced labor risk assessment tools have largely been too qualitative or inexact to inform targeted and effective risk mitigation efforts.

To address this, GFEMS has developed an award winning forced labor screening tool that predicts the risk of forced labor at the firm level using operational features like the number of known trade partners, financial information, and geography. The Fund intends to release the prototype open source for investors, supply chain management platforms, and NGO watchdogs to further develop and integrate into their own platforms, elevating the issue of forced labor in due diligence and procurement. This effort is key to ultimately mobilizing trillions in private sector procurement and ESG investment to sustainably address forced labor.

The Fund also leverages the expertise and analytics capabilities of the financial sector to improve efforts to identify and disrupt illicit financial flows to traffickers. As part of this workstream, GFEMS kicked off the Cross Industry Data Initiative (CIDI) in early 2020. Working with The Knoble and SAS, the Initiative convenes financial crime professionals, financial institutions, law enforcement experts, and NGOs in a series of working groups to address data-sharing challenges and build partnerships necessary to implement solutions.

We look forward to sharing future updates about our growing Global Finance portfolio and partnerships. Together we can create and implement actionable solutions for ending modern slavery.

To stay updated on this project, and projects like it, subscribe to the GFEMS newsletter and follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Have an idea for innovative finance?

Cross Industry Collaboration Against Trafficking: CIDI Initiative gains steam

Cross Industry Collaboration Against Trafficking: CIDI Initiative gains steam

Before the onset of COVID-19, GFEMS and its partners at The Knoble and SAS Institute were scheduled to host a Cross Industry Data View workshop, building on the work of the Liechtenstein Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking (FAST) Initiative. The workshop, acting as a platform to explore opportunities accelerating progress in financial sector mobilization, was intended to be the starting point for building a roadmap to a cross-industry data view of financial transactions. Such a data view could enable financial institutions to better identify and track illicit financial flows.

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the workshop was taken online in the form of a webinar, and interest in the project has gained momentum. Since the Initiative launched in May, more than 130 participants from over 60 organizations across government, financial institutions, fintech, and NGOs are working together virtually to identify actionable steps to facilitate better data gathering and sharing and paths for collaboration between public, private, and nonprofit sectors. Contributing their expertise to the Initiative across five working groups, Data, Law Enforcement and Regulations, Role of the NGOs, Scams and Abuse, and Ideation, CIDI participants have dedicated over 1200 hours to the project.

Shawn Holtzclaw, Acting Executive Director of The Knoble and leader of the Ideation working group, said, “We are facing a challenge that requires collaboration, ingenuity and determination. Through CIDI I am confident we’ll begin to create systemic impact.”

The CIDI initiative was created to address the need for improved partnership in data sharing by financial institutions to improve visibility into illicit financial flows. Financial institutions have different views of transactional and account activity, resulting in only partial or fragmented understandings of potentially illicit financial flows. There is an opportunity to create a more holistic picture of account activity through improved collaboration and communication between financial institutions and by developing a cross-industry data view that utilizes pre-existing infrastructures and capabilities within the financial sector. Ultimately, this improved data view has the potential to accelerate efforts to identify and disrupt illicit financial flows to traffickers.

The CIDI working groups will continue to meet throughout this quarter, each working on specific proposals and identifying needs and opportunities to advance the goals of the Initiative. GFEMS looks forward to continuing this work and sharing our results and findings into the future.

To learn more about the CIDI initiative or the Fund’s partnership with The Knoble, please visit our website, follow us on Twitter and subscribe to our newsletter.

GFEMS and The Knoble Partner to Mobilize the Financial Sector to Eliminate Human Trafficking

GFEMS and The Knoble Partner to Mobilize the Financial Sector to Eliminate Human Trafficking

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) and The Knoble have announced a formal partnership to advance efforts to end modern slavery by identifying and disrupting the financial flows that enable human trafficking operations.

This is a tremendous challenge. An estimated 80% of fraud is facilitated by organized crime resulting in over $150 billion dollars in profit, and more than 40 million people live in modern slavery—that translates to 1 person every 4 seconds becoming a victim.

Through this partnership, existingnetworks of fraud, cyber, fintech, and financial crime professionals will develop strategies, provide tools and facilitate partnerships to identify and disrupt financial flows to traffickers and more effectively mobilize the financial sector in the fight against human trafficking. Relevant resources will be scaled globally and made available for other organizations to adopt directly or replicate.

“The only way to protect vulnerable populations from human trafficking and modern slavery is through coordinated efforts that educate and equip financial professionals with tools to detect and prevent these threats,” said Shawn Holtzclaw, Executive Director of The Knoble. “It’s an honor to partner with GFEMS. The combination of its continued commitment to mobilizing the financial sector and our unparalleled industry expertise will allow us to implement practical safeguards that affect positive change around the world.”

“Our team is proud to work alongside and learn from this incredible network of financial crime experts. We are committed to engaging the private sector to co-develop solutions and leverage technology, data, and expertise to more effectively disrupt illicit financial flows to traffickers and protect the vulnerable. The response to the Cross-Industry Data Initiative to-date has been overwhelming and points to the passion and commitment of our partners at The Knoble to drive action,” said GFEMS Director of Strategic Partnerships, Natalya Wallin.

The Fund’s ongoing efforts to mobilize the financial sector build on its partnership with Liechtenstein and other key partners committed to ending modern slavery by making it economically unprofitable. ”

About GFEMS

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) is a bold international fund catalyzing a coherent global strategy to end human trafficking by making it economically unprofitable. With leadership from government and the private sector around the world, the Fund is escalating resources, designing public-private partnerships, funding new tools and methods for sustainable solutions, and assessing impact to better equip our partners to scale and replicate solutions in new geographies.

About The Knoble

Founded in 2019, The Knoble is dedicated to protecting vulnerable populations around the world, including victims of modern slavery, human trafficking, elder abuse and child exploitation. Led by volunteers (Knights) that are experts in fraud, financial crime, financial services, data, and technology, The Knoble’s cross-industry initiatives in the public, private and charitable sectors create an ongoing, system-wide effort to detect and prevent criminal abuse. For more information, visit www.theknoble.com.

To learn more about our work or our partnerships, follow us on Twitter and Medium and subscribe to our newsletter.

Fostering Financial Sector Collaboration to End Modern Slavery

Fostering Financial Sector Collaboration to End Modern Slavery

This month the Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) is co-hosting a Cross-Industry Data View webinar in partnership with The Knoble and SAS Institute. The webinar will cover the work to-date of the Liechtenstein Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking (FAST) Initiative and explore specific opportunities to accelerate progress. This will be followed by an in-person workshop later this year where participants will build a roadmap for creating a cross-industry data view of financial transactions.

These expert convenings are part of the Fund’s ongoing commitment to mobilizing the financial sector against trafficking and slavery, following the launch of the Liechtenstein Initiative’s Blueprint for Mobilizing Finance Against Trafficking and Slavery at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2019. In alignment with the Fund’s approach, the workshop will foster collaboration across sectors by bringing together representatives from financial institutions, government, anti-trafficking organizations, and the FAST Initiative.

Financial institutions have different views of transactional and account activity, resulting in only partial or fragmented understandings of potentially illicit financial flows. There is an opportunity to create a more holistic picture of account activity through improved collaboration and communication between financial institutions. It may be possible to develop a cross-industry data view by utilizing pre-existing infrastructures and capabilities within the financial sector. Ultimately, this could accelerate efforts to identify and disrupt illicit financial flows to traffickers.

In the upcoming workshop, GFEMS and its partners will work side by side to identify actionable steps for creating this data view to enable institutions to proactively share relevant information. Participants will focus on identifying opportunities to improve information sharing across institutions, clarify what information needs to be shared, and pinpoint outstanding challenges to be addressed. Following the workshop, participants will develop a project roadmap that includes clear steps and milestones to creating a cross-industry data view.

GFEMS thanks The Knoble and SAS Institute for their partnership and looks forward to continued collaboration with the financial sector as part of its overarching strategy to end modern slavery by making it economically unprofitable.

Read more from GFEMS on mobilizing the financial sector to end modern slavery and human trafficking.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter for the latest information on our activity.

==

The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) is a bold international fund catalyzing a coherent global strategy to end human trafficking by making it economically unprofitable. With leadership from government and the private sector around the world, the Fund is escalating resources, designing public-private partnerships, funding new tools and methods for sustainable solutions, and assessing impact to better equip our partners to scale and replicate solutions in new geographies.

Liechtenstein joins GFEMS in the Fight to End Modern Slavery

Liechtenstein joins GFEMS in the Fight to End Modern Slavery

The Government of Liechtenstein has announced a contribution to the Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) to support the bold vision of an international fund and accelerate efforts to end modern slavery by making it economically unprofitable.

GFEMS is proud to welcome Liechtenstein to the Fund and looks forward to working together closely. Liechtenstein has demonstrated global leadership and a commitment to innovation in addressing modern slavery.

In 2017 Liechtenstein signed the call to action to end modern slavery issued by the United Kingdom at the UN General Assembly. Following the call to action, Liechtenstein launched the Financial Sector Commission on Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking. GFEMS served on the Commission throughout 2019 and contributed to the Blueprint which was released at UNGA in September of 2019. GFEMS remains committed to mobilizing the financial sector as a critical component of the coherent global strategy to end modern slavery.

This newly announced contribution to GFEMS further demonstrates the Liechtenstein government’s public commitment to ending modern slavery. The Liechtenstein Government’s contribution will support innovative efforts to mobilize the financial sector.

“GFEMS welcomes Liechtenstein’s leadership and partnership as we build global momentum towards ending modern slavery alongside governments, civil society, and companies around the world,” said GFEMS Board Chair Jean Baderschneider. “Their commitment to mobilizing the financial sector by both tracking illicit financial flows to deny traffickers profits and by promoting responsible investment in companies acting in good faith to address forced labor risks in supply chains is a key component of sustainably ending modern slavery.”

Questions about this announcement may be sent to media@gfems.org.