The world is paying more attention to mental health. COVID-19 undoubtedly elevated the conversation as extended lockdowns took their toll on virtually everyone’s mental state. Today, we see advertisements for anti-depression pills and anxiety treatments regularly cross our screens; we hear celebrities talk of managing mental health and sports stars actively promote talk therapy; many doctors accustomed to treating our physical ailments are beginning to inquire about our mental health. The world may be paying more attention, but are we really doing enough to prioritize mental well-being?

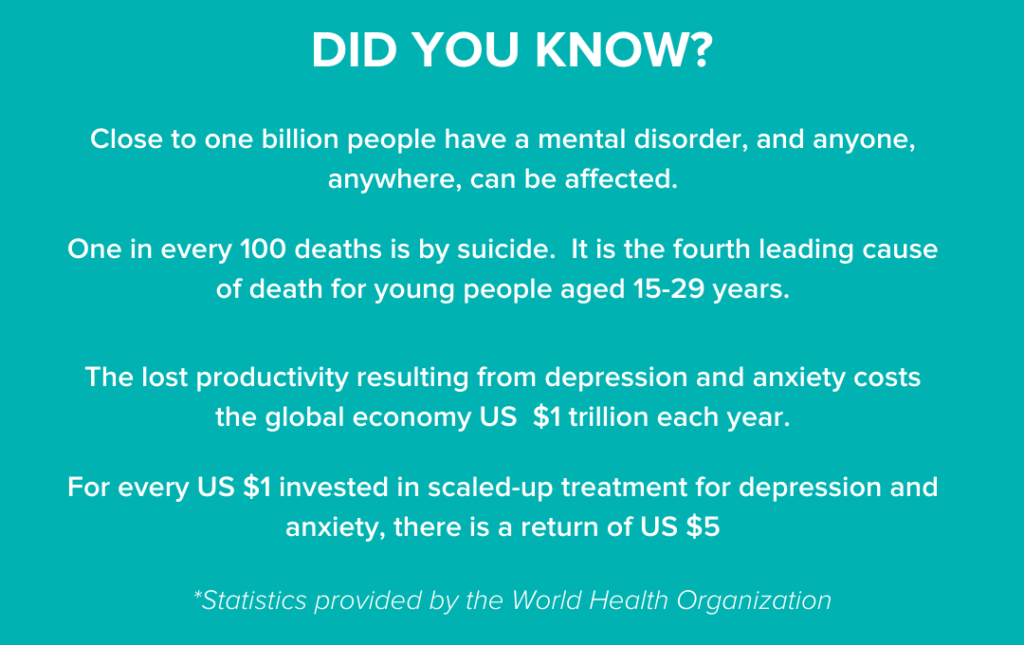

According to the World Health Organization, nearly one billion people have a mental disorder. One BILLION. The cost to the global economy is about $1 trillion each year in lost productivity resulting from depression and anxiety, two of the most common mental disorders. Perhaps even more startling- more than 80% of people experiencing mental health conditions are without any form of quality affordable mental health care.

While mental health disorders can affect anyone anywhere, they are especially common among those confronting and coping with crisis, trauma, or a history of abuse. Those like Farishta– who had gone abroad to earn a better wage as a domestic worker but instead met exploitation and abuse at the hands of her employers. Though Farishta eventually returned to Bangladesh, she did so without the money or savings that was expected. She was shunned by a family and community that branded her a failure. Farishta struggled with thoughts of taking her own life before she was introduced to Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP), a community-based migrant workers’ organization, that helped her heal physically, mentally and emotionally.

For Farishta, mental health services were a critical part of recovery and reintegration. Not only for her but for her family. With both participating in counseling sessions, Farishta was able to reconnect with a son who, after refusing to call her mother, now understood her trauma.

As both practitioners and survivors recognize the importance of mental wellbeing, mental health has become a cornerstone of the modern anti-slavery movement. Indeed, it has to be. Study upon study shows that survivors are more likely to battle depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), even self-harm. We also know that mental health needs, when left unmet, can increase a person’s risk of being trafficked or perpetuate a cycle of victimization.

The call for trauma-informed and survivor-centered care has grown louder in recent years. It’s an approach that guides much of our anti-trafficking programming, supporting survivors to heal in ways that pay mind to the effects of trauma and the experiences of those who live it.

But, even if “the field” is centering mental and emotional well-being, does that mean we are? Mental health may be a central feature of anti-trafficking programs and research, but what about the individuals who are implementing those programs or the researchers conducting the studies? Is mental health a priority? Does it need to be?

Put Your Own Oxygen Mask on First

Its guidance that seems to make more sense when you are 35,000 feet in the air and delivered as part of a flight attendant’s do-or-die safety message, but somehow it feels less applicable when our feet are planted under a desk, our thoughts on programs that support others- even less applicable still when we spend a greater part of everyday working directly with survivors of human trafficking.

As practitioners, we advocate for trauma-informed and survivor-centered approaches to care, and we abide a “do no harm” mantra. We develop guidance and best practices for working with survivors and vulnerable populations and we commit to following them; we share what we know in trainings and convenings and we improve together; and then we monitor and evaluate to make sure what we are doing is working for the people we serve and we try to fix it when it isn’t.

Confronting stories of sexual exploitation, forced labor, and human rights abuse daily, there’s a heaviness about the work we all do. It’s a heaviness that often makes it hard to close the laptop at the end of the day or to ignore that “you have mail” ping first thing in the morning. And for those who engage more directly with survivors, that heaviness can weigh greater.

GFEMS is not a direct service provider, but there are some on our team who were. They can attest that “burnout” is in fact very real. One GFEMS staff member recounts how she quite literally witnessed burnout before she herself chose to leave direct service work. “Personally, what made me leave direct service work was burnout and the fact that the current system is built on measuring the number of people impacted without thinking about the care of the people actually producing these numbers. I saw more than three members of my team burnout and have mental breakdown without the system having a process for support.”

So how do we prevent burnout? How do we set up processes for support? How do we continue to do the important and necessary work while still looking after our own mental wellbeing?

It helps when you are part of an organization that takes mental health seriously. And, thanks in no small part to our small and mighty HR team, the Global Fund does. They are our constant reminder that we need to take time for ourselves- advocating for policies like more Administrative Days, peppering our inboxes with self-care tips and words of inspiration, and encouraging us all to use the mental health services and resources the Fund provides.

On a more personal note, we all have activities and people we enjoy. Finding time for them is one of the best things we can do for ourselves, for our work, and for those we seek to support (it’s true, there are studies that say so. See here.) Of course, this looks different for every person.

It may feel selfish to turn your gaze away from the work- even if only for a bit- but ask any new parent how it feels to get a few hours of me-time. It’s reinvigorating, a real game-changer. You tag back in with an energy and enthusiasm to do more and to do it better. It’s good for you. It’s good for them. It’s good for the work.

Or you can ask the former practitioner who burned out and left.

For Mental Health Resources for Human Trafficking Survivors and Allies, see https://www.acf.hhs.gov/

…